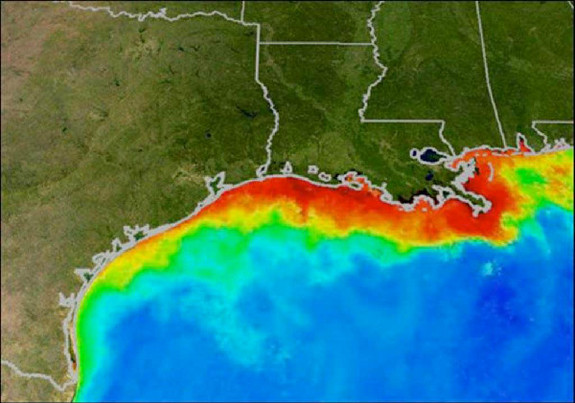

Huge 'Dead Zone' Predicted in Gulf of Mexico

A very large dead zone, an area of water with no or very little oxygen, is expected to form in the Gulf of Mexico this year — a trend in recent years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Computer models put together by scientists predict that the zone will cover an area between 7,286 and 8,561 square miles (18,871 to 22,173 square kilometers) this summer, the typical time for such zones to form. The large end of the estimate is roughly the size of the state of New Jersey, and would be the largest dead zone ever recorded. The biggest one recorded to date, in 2002, reached 8,481 square miles (21,966 square km).

Meanwhile, models predict the dead zone in the Chesapeake Bay will be smaller than usual.

The makings of a dead zone begin with nutrient pollution, primarily fertilizers and agricultural runoff. Once these excess nutrients reach the ocean, they fuel algae blooms. The algae then die and decompose in a process that consumes oxygen and creates lifeless areas where fish and other aquatic creatures can't survive. This zone can have serious impacts on commercial and recreational fisheries on the Gulf Coast.

Conditions are ripe for a large dead zone this summer, thanks to heavy rains throughout much of the Midwest this spring that have caused water nutrient runoff (for example, from farm fertilizer) with it, according to a NOAA statement.

Last year's dead zone was smaller than average due, in large part, to the drought that gripped much of the country. It reached a maximum size of about 2,889 square miles (7,483 square km), an area slightly larger than the state of Delaware. Since 1995, the average Gulf dead zone has been 5,960 square miles (15,436 square km), an area a little larger than the size of Connecticut.

The official size of the Gulf hypoxic, or dead zone, will be released in August, according to the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.com.