Legend of Lost City Spurs Exploration, Debate

Deep in the dense rain forests of Honduras, a glittering white city sits in ruins, waiting for discovery. The inhabitants there once ate off plates of gold; the metropolis was, perhaps, the birthplace of a god. A recent high-tech survey of the region by air reveals possible pyramids and other structures. Has the lost city of Ciudad Blanca been found? Or did it ever exist at all?

Probably not, according to archaeologists and anthropologists, who generally agree there was once something in the eastern Honduras rain forest — though likely not a city of mythical wealth and luxury. In fact, the legend of this ancient city may be a relatively new one, said John Hoopes, an archaeologist and specialist in southern Central American cultures at the University of Kansas.

"I think the media is contributing to the growth of a legend," Hoopes, who was not involved in the ruins' discovery, told LiveScience. "And it's one that has really yet to be shown to have any basis at all in the scientific reality." [20 Mythical Worlds: Science Fact or Fantasy?]

The legend could be dangerous, Hoopes warned: If people become convinced that a gold-laden city is hiding in the Honduran rain forest, it could encourage looting, he said, damaging the real archaeological sites that no doubt lurk among the tropical vegetation.

On the other hand, a legend that spurs conservation could be exactly what this threatened region needs.

A lost city, or simply a myth?

The legend of Ciudad Blanca arose from fragments and snippets of stories. In the 1520s, conquistador Hernan Cortes wrote to the Spanish Emperor Charles V of a reported wealthy province called Hueitapalan in the region. In 1544, another Spaniard, Cristobal de Pedraza, the Bishop of Honduras, claimed to have glimpsed a white city in his travels; he later wrote that his guides told him the inhabitants of the city ate from gold plates, so great was their wealth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But only in the last century did the myth of the white city gain steam. Expeditions in the 1930s exploring the remote Mosquitia region where the legendary city supposedly sits turned up local rumors of lost cities, but no actual evidence. Perhaps the most detailed "discovery" of Ciudad Blanca appeared in 1940, when an adventurer named Theodore Morde claimed to have found extensive ruins deep in the jungle. Morde claimed that his guides told him tales of a temple dedicated to the worship of a monkey god. Today, Ciudad Blanca is also sometimes cited as the birthplace of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, despite that fact that the Mosquitia region is far from the former Aztec empire in what is today Mexico.

Unfortunately, Morde never revealed the location of his supposed discovery before his death by suicide in 1954. The death spawned conspiracy theories but no answers as to the legend of the lost city.

"It's all a bunch of little stories, and they sort of change depending who you're talking to," said Steve Elkins, a documentary filmmaker whose quest for ruins in the Mosquitia region has spurred the latest round of Ciudad Blanca fever.

Exploration and preservation

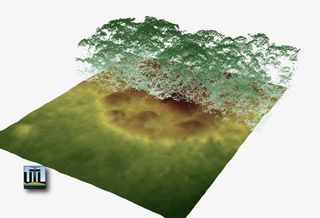

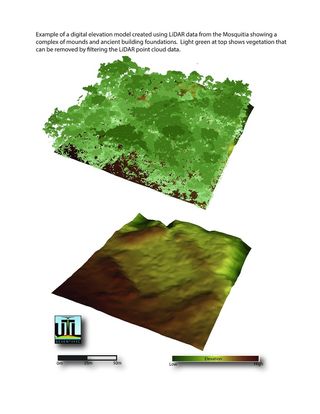

In 2012, Elkins and his colleagues announced they had discovered hints of ruins in the Mosquitia forests. Their expedition was higher-tech than those that came before: Elkins and his team flew over the rain forests in an airplane shooting laser pulses at the ground in a method called light detection and ranging (LiDAR). [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

LiDAR allows researchers to create digital maps of the terrain below the forest canopy, something that aerial photography and satellite imagery can't reveal, Elkins told LiveScience. The filmmakers later brought on Colorado State University archaeologist Chris Fisher to interpret the strange shapes they uncovered.

"It's pretty incredible," Fisher told LiveScience. The LiDAR data reveals roads, canals and mounds, which appear to cover archaeological features. There are two large settlements and about 100 smaller ones, Fisher said.

As amazing as the find may be, it has been overstated by some reports, Fisher said. "There's no gold, okay?" he said. "There's no space aliens. We don't know if this is Ciudad Blanca."

The documentary team has worded announcements of the discoveries with care — they are "utilizing LiDAR technology to seek ancient settlements and human-constructed landscapes in an area long rumored to contain the legendary city of Ciudad Blanca," as one press release puts it — but the ruins have nevertheless become linked with the legendary city, absent any evidence it really existed.

"Urbanism implies a dense and large population," Hoopes said. "We don't know how large or dense a population might have existed in eastern Honduras."

Elkins is fascinated by the local tales of Ciudad Blanca, but he's not claiming a discovery, either.

"Certainly, we're making a documentary, and that's part of the attraction," Elkins said of the legend. But there is no way to know whether the ruins he and his team have found are one and the same as the ruins reported in vague local legends and hyped-up travelogues of the early 1900s.

"How would you ever know if you'd found Ciudad Blanca?" Elkins asked. "I doubt there's a sign that says 'Welcome to Ciudad Blanca.'"

Exploration and preservation

In many ways, Hoopes said, the problem with the Ciudad Blanca media hype echoes crises at archaeological sites around the world: How do you protect a "lost" city once it's found?

Elkins and his team aren't telling the coordinates of the ruin-like shapes they've discovered, a choice Hoopes called "very responsible." Keeping sites secret makes life harder for archaeologists, however, as it's tough to critique your peers' work when you don't know where it is. Nevertheless, an area like the Mosquitia region lacks the law enforcement to deter looters, so secrecy is the best protection, Hoopes said. With satellite, GPS and other technologies just about anyone could easily find a site, and Ciudad Blanca may be at particular risk because of legends that it contained massive amounts of gold, he said.

"If people think there is gold there, they'll go searching for it and that results in the disruption of architectural features and looting," Hoopes said.

The good news for whatever ruins are in the area is that the Mosquitia region is incredibly remote, Elkins said. There are no roads, and a journey by foot and canoe would take weeks. Nevertheless, Elkins said, he worries about the publicity spawned by the Ciudad Blanca legend, too.

"It is a concern," he said. "Sometimes I go, 'Maybe I opened up a Pandora's box,' and that thought crosses my mind. But I go, 'Okay, this is what we did. It's not like we went to a place where people thought there was nothing. People are always trying to find it.'"

What's more, Elkins said, is that the Mosquitia region is in danger even without the Ciudad Blanca legend — perhaps more so. Illegal logging is eating away at the forests, he said. He hopes an archaeological expedition to the region will end up protecting it in the long run.

What's next for Ciudad Blanca?

Protection is the other side of the publicity coin, which has spurred fierce debate over how to announce discoveries like the one in the Mosquitia region.

"People can't conserve something if they don't know it's there," Fisher said. As archaeologists increasingly turn to LiDAR, revealing sites previously gone unnoticed, the problem of publicity versus secrecy will only increase, he predicted. [Images: LiDAR Reveals Ruins Near Angkor Wat]

"How do we publish them? How do we release them?" Fisher said of the LiDAR data sets. In some threatened areas, LiDAR may be the only chance to see archaeological ruins before they're destroyed by development, he said. What's more, he said, LiDAR data could help conservationists, showing, as it does, everything from natural water features to topography to the size of trees in the forest.

Fisher argues that shining a light on previously unnoticed sites is the best way to protect them. In the case of the Mosquitia ruins, the legend of a lost city may help. Since 1960, a 2,000 square mile (5,180 square kilometers) portion of the region has been designated the Ciudad Blanca Archaeological Reserve, testament to the importance of the legend in Honduran culture. Recently, Honduran president Porfirio Lobo Sosa has been supportive of the explorations, calling them good for the country, according to The New Yorker.

Elkins, Fisher and their team are planning an on-the-ground expedition to the ruins by the end of the year (they'll reach the area by helicopter and bushwhacking). Neither expects to find the treasures of myth — "I would drop dead if I found anything made of gold," Fisher said — but they do expect to survey the mounds seen in the LiDAR data. The goal is to "ground truth" the findings, Elkins said, ideally kicking off excavations and more extensive ground exploration of the ruins — a worthwhile project even without a shining white city brimming with gold.

"Who knows, it may be something even more fantastic," Elkins said. "You don't know until you go."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular