Virtual Reality Could Hone Brain Surgery Skills

MONTREAL — With blood pooling in his head, the "patient" didn't stand a chance.

Rookie after rookie stepped up, trying to attack the patient's brain tumor with surgical tools, but thankfully for the suffering patient, the surgery was a simulation at the Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University.

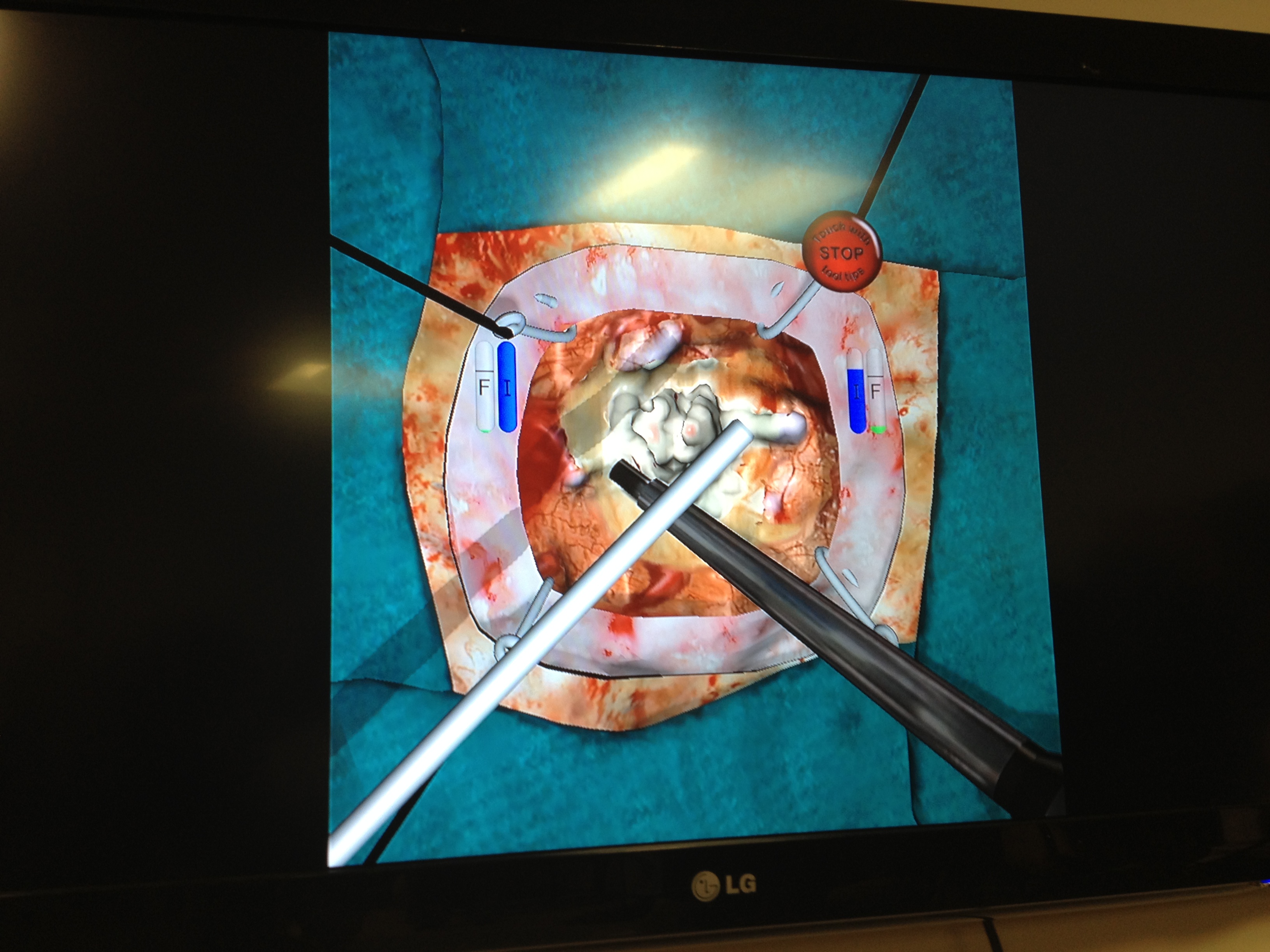

The institute, affectionately known to residents as "The Neuro," is the site of a surgery simulation technology called the NeuroTouch Cranio, which is billed as one of the most advanced brain surgery tools worldwide.

Commercial pilots generally learn the trickiest aspects of flying in simulators. NeuroTouch's proponents argue that doctors should also train for surgery using simulators, especially because mistakes in surgery could be deadly.

"Our main goal is to improve the resident training. Previously, they were receiving that directly from the operating room," said Dr. Hamed Azarnoush, a postdoctoral fellow at The Neuro. He spoke with reporters on June 6 during the Canadian Science Writers' Association annual conference.

Preventing costly mistakes

Canada is lagging behind other nations in some aspects of surgery, according to a 2011 report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Compared with the countries included in the report, Canada recorded higher-than-average "adverse events" during surgery, such as inadvertently puncturing or lacerating the patient, or accidentally leaving surgical equipment behind.

Surgeries to remove tumors present particular challenges to doctors. Removing growths can damage surrounding tissues, including blood vessels and nerves. But if part of the tumor is left behind, it could regrow and require more surgical intervention, increasing the risk to the patient.

NeuroTouch provides residents and doctors the chance to figure out how to approach complex procedures, without needing to open up a real person, Azarnoush said.

The surgical tools doctors grasp in the simulator provide artificial sensations similar to the real deal. Meanwhile, a screen shows an HD simulation of a tumor, and the tools' effects on it. This lets surgeons learn their way by feel as well as sight.

'This is not something that can be brought in right away'

The simulator, built in conjunction with Canada's National Research Council, is 3 years old and is currently being used in training studies.

Researchers have praised some benefits of the technology in published papers, but it is still at least several years away from being implemented for career neurosurgeons, said Dr. Rolando Del Maestro, the director of the institute's Neurological Simulation Research Centre.

"This is not something that can be brought in [to surgical training programs] right away. You can imagine the backlash would be on something like this," Del Maestro told LiveScience.

Instead, he said it would be a gradual process, as trainees today complete simulator work and become doctors themselves. Then they might be more accepting of completing refresher training on the computer, similar to how pilots do it, he added.

Early studies on medical students using NeuroTouch Cranio show the simulator could eventually be used to identify which have excellent surgical skills, and which might require more training.

As neurosurgeons in training are often not rejected for technical skills until near the end of their five or six years of school, this could provide remedial action much sooner in the process, Del Maestro said.

How to learn brain surgery

Before being used as an operating tool, the simulator must demonstrate several stages of competence: it must look similar to a real operation, teach skills usable in real patients, distinguish expert surgeons from novices, and solve real-world problems.

Papers have been published concerning the first two of these skills, and several other studies on the third skill are being assessed for a number of different neurosurgical operations, Del Maestro said.

A paper accepted for publication with the International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology, for example, evaluates the technical skills of selected medical students, junior and senior residents and provides metrics for each one.

"It shows three junior residents who are very good [with NeuroTouch.] Those three are actually better than the senior residents," even though they've been with the program for a shorter time, Del Maestro said.

"One of those questions you can ask are if those individuals have potential to become expert neurosurgeons, world-class international ones who have those technical skills."

Starting tomorrow (June 21), Del Maestro will helm another study at McGill that he terms the "Kobayashi Maru" for neurosurgeons, named after an infamous no-win scenario test in "Star Trek."

In this study, doctors and medical students will operate in the NeuroTouch on a bleeding tumor that cannot be fixed, meaning the patient will die as they work.

"What we’re doing is during that scenario, we’re measuring their EEG [brain activity], heart rate, muscle tension, all these other aspects," Del Maestro said.

"We want to find out what are the stresses that are involved in that particular scenario, and can we train the residents to deal with those stresses."

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook& Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.