Source of Fungal Infection Outbreak a Mystery, CDC Says

In the largest outbreak ever reported in the U.S. of blastomycosis, a fungal infection with flulike symptoms, 55 people in central Wisconsin became sick in 2010.

The fungus that causes blastomycosis is commonly found in soil, but exactly what triggered the spike in cases in Marathon County remains a mystery, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Wisconsin health officials.

Unlike a blastomycosis outbreak in a neighboring Wisconsin county in 2006, in which a pile of waste in a large yard was the likely source, the culprit in this episode remains elusive.

"We didn't find evidence for a single source in the environment that could explain all the cases," said Kaitlin Benedict, an epidemiologist with the CDC's Mycotic Diseases Branch, who was involved in the research. "We think there were probably multiple 'hot spots' for the fungus in several different neighborhoods."

It's also unclear why infection rates among Asians, particularly those of Hmong descent, were about 12 times higher than non-Asians, the report said.

Some 45 percent of people affected by the outbreak were of Hmong ethnicity. This group is originally from Southeast Asia, but many of those who became sick in the outbreak had been living in Wisconsin for more than a decade, according to the report.

The large number of cases among the Hmong was one of the most surprising things about this outbreak, Benedict said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is the first known report of Asians being disproportionately affected" by the fungal illness, she said, adding that previous studies have shown high blastomycosis rates among African-Americans in other U.S. states.

The report was published online (June 3) in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Searching for clues

Benedict said the exact reasons why Hmong people were at higher risk for falling ill in this outbreak were unclear.

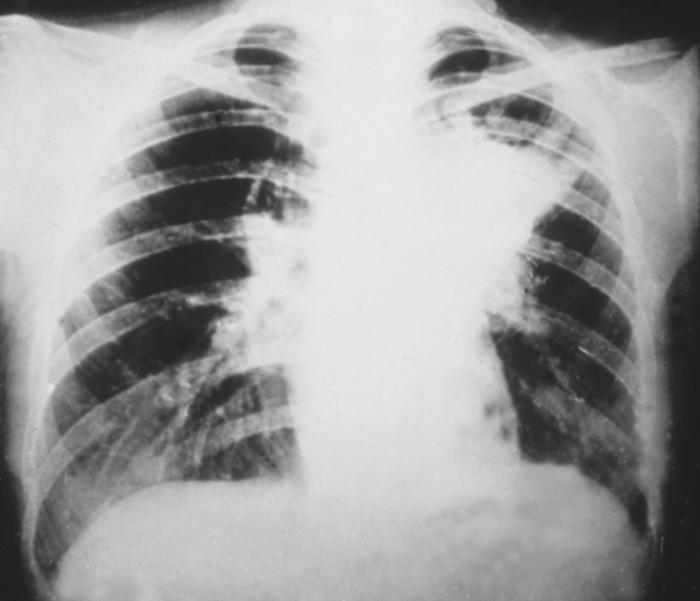

The fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis lives in the soil typically in the Midwest and Southeast U.S. Its spores are found near decaying leaves and wood, where they can be inhaled and cause lung infections.

In the report, the CDC investigators explain they were called in to figure out why Marathon County residents were seeing a spike in the number of reported cases of blastomycosis. State health officials also noticed that cases seemed to be clustered together geographically, in specific neighborhoods and in certain households.

Investigators found that during the 10-month period between September 2009 and June 2010, 55 people in the county became infected with Blastomyces dermatitidis, most of whom were adults. Two deaths occurred during the outbreak, and 30 people were hospitalized.

Slightly more males than females became ill, and nearly one-quarter of the people who had the fungal infection had pre-existing health conditions, such as lung disease, cancer or diabetes.

Still, "we could not identify any activities or exposures that put people at increased risk," Benedict said.

Mysteries remain

Other research had suggested that people who got sick from blastomycosis were probably exposed to the fungus while participating in outdoor recreational or work-related activities. But investigators did not find that Asians were not more likely to camp, fish, hike, hunt or hold jobs that put them at increased risk compared with people unaffected by the outbreak.

It's possible that the Hmong fell victim to this fungal outbreak because of genetic differences that involve the immune response, Benedict said. She explained that previous studies have shown that people with these types of genetic differences are more susceptible to the severe forms of other fungal diseases that are similar to blastomycosis.

The Marathon County outbreak ended after July 2010, when the number of cases tapered off. Researchers suspect that weather-related changes, such as rainfall and temperature shifts, lessened the amount of fungal growth and brought about the end.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com .

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents