Mapping Puerto Rican Heritage with Spit and Genomics

When it came time for students to pick genes to study from the genomes of their fellow Puerto Ricans, Alexandra Wiscovitch chose those responsible for hair and eye color. As a modeling teacher, she had noticed her students had a variety of both.

"You think of Puerto Ricans, and you think of all of us having brown eye color and brown hair color," Wiscovitch said.

Fellow student Jorge Irizarry Caro's interest in studying medicine, particularly cardiology, helped him select a gene that may play a role in heart attack.

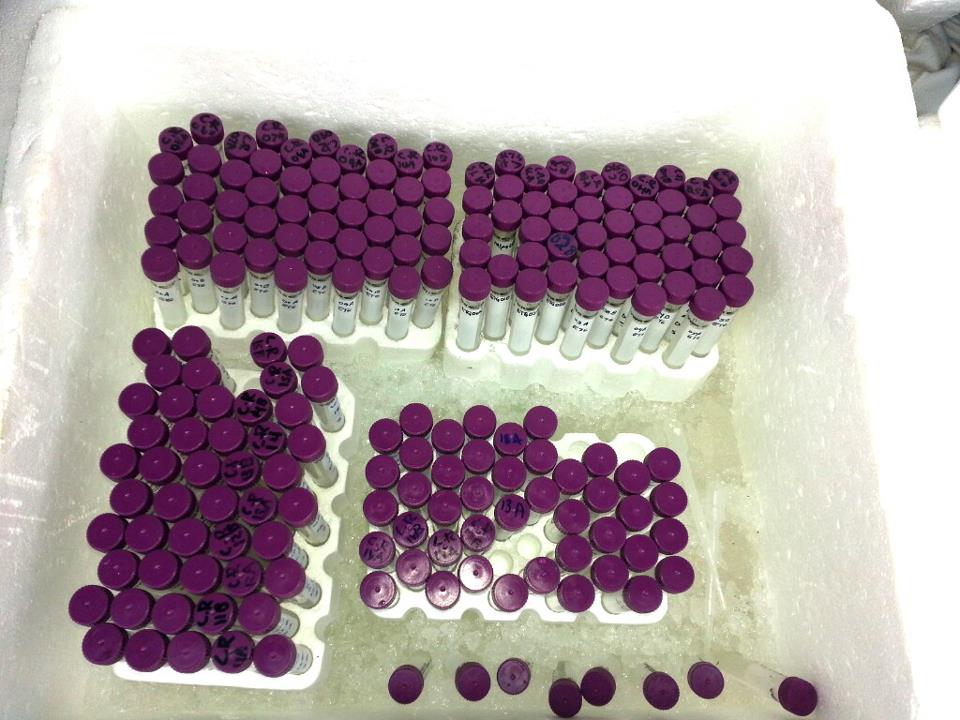

Wiscovitch and Caro are among the student researchers mapping the genetic heritage of Puerto Rico, based on the DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) in spit samples they have been collecting from local people on beaches, in shopping malls and other public places across the island.

The genetic material they collect contains clues to Puerto Rican ancestry — a mix of African, European and American Indian — susceptibility to disease and prominence of other traits, such as hair and eye color. [8 Surprising Facts About Hispanics' Health]

"That is the goal we are moving toward, to describe genetic diversity across the island and do it in a kind of crowdsourcing way, one study at a time," said Taras Oleksyk, the principal investigator for the project, Local Genome Diversity Studies (LGDS), at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez. "And hopefully, we'll come up with something on the big picture."

As a population geneticist, Oleksyk believes "the most interesting thing is how different people came to Puerto Rico and how they brought different genetic characters with them."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This "story of the people" can be applied to understand how individual Puerto Ricans react to environmental conditions and the disease risks they face, he said.

Mixed heritage

The students are approaching their goal of collecting 96 samples from the island's 78 municipalities. Yashira M. Afanador, a graduate student, has begun the analysis that will lead to detailed maps of ancestry patterns across Puerto Rico.

"Our goal is to have a more representative sample from all of the island, because all the studies that have been done, they have been done in very small samples and scattered around the island," Afanador said.

One of these earlier studies, published in PLOS ONE in 2011, found that on average Puerto Ricans' ancestry is 15 percent American Indian (known as Taino), 21 percent African and nearly 64 percent European. But this ratio varies across the island, with more European background on the west side of the island and more African on the east side.

Whereas that study looked at genetic markers inherited from both parents (called autosomal markers), earlier work used markers inherited from the mother to find a much larger share of ancestry from Tainos. This result likely reflects the history of male immigrants marrying the local Taino women.

When the students approach people, these potential donors are particularly interested in research on Puerto Rican heritage.

"Everyone wants to be Taino," she said, referring to the indigenous people living on the island when Europeans arrived. "When we collect samples, they say 'that's my main ancestry.'"

Future medicine

The LGDS project may also help explain why certain diseases, particularly asthma, affect Puerto Ricans more than other mixed populations, such as Mexicans, say those involved.

Ultimately, Caro sees the project as a way to improve health care for Puerto Ricans through personalized medicine, "so, if you go to a hospital, they know you are predisposed to heart attacks because of your genetic ancestry," he said. [7 Diseases You Can Learn About From a Genetic Test]

Caro's research focuses on a gene, known as LTA4H. Variants of this gene have been shown to increase risk of myocardial infarction (commonly called heart attack) markedly among African-Americans. (Cardiovascular disease has been increasing in Puerto Rico, and is now the second-most common cause of death on the island, according to Caro.)

Caro looked for specific variants in LTA4H in samples from municipalities with high African ancestry and in others with high European ancestry. He found these variants did indeed show up at high frequencies in the more African municipalities.

Ultimately, he plans to map the frequency of the variants across the island.

Hidden red hair?

Meanwhile, Wiscovitch has been looking at genes associated with hair and eye color, including a variation linked with red hair. While analyzing samples from the east side of the island, she found something surprising.

"In the east side of Puerto Rico where there is the highest concentration of Africans there is also the highest concentration of the red hair [gene variant],” Wiscovitch said. "So black people are supposed to have red hair there."

She had expected to see more of this genetic variation in parts of Puerto Rico with more European ancestry.

In the fall, she is planning follow-up research that will incorporate information about the participants' hair color. It is possible that the red hair gene is not expressed in people who have dark hair, she speculated.

Work continues

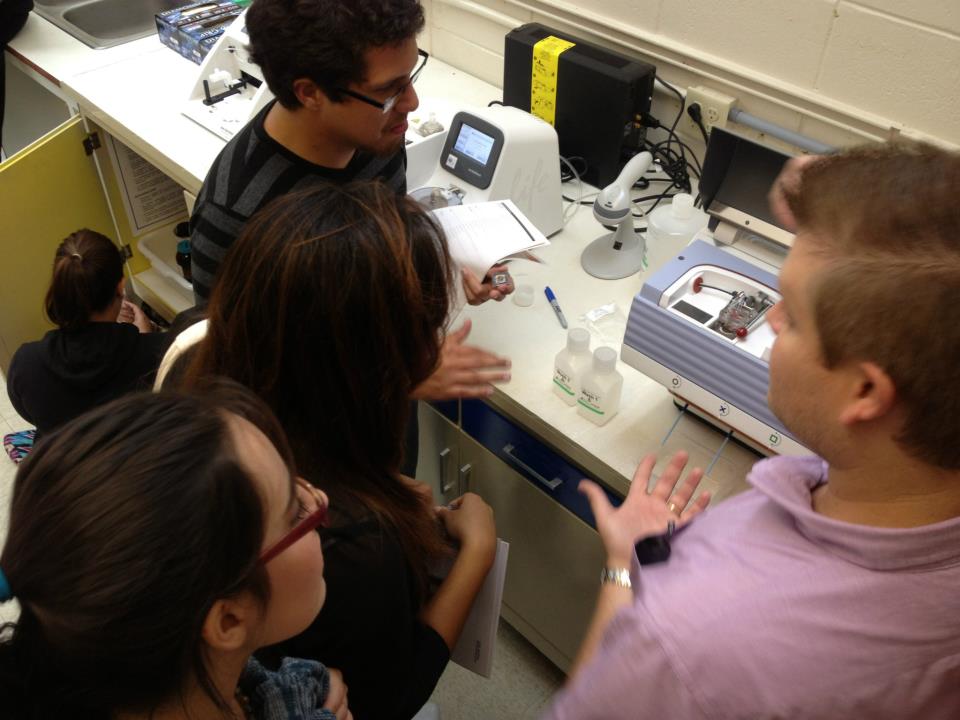

Students continue collecting samples and learning how to extract DNA as part of LGDS, which is funded by the National Science Foundation through August. Ultimately, the students will develop their own research projects, just as Caro and Wiscovitch did, and seek outside funding to support them, Oleksyk said.

LGDS grew out of Oleksyk's experience taking students door-to-door with colleague Juan Carlos Martinez-Cruzado in 2010 to recruit participants for the 1000 Genomes Project, which is cataloging rare variation in many populations. Now both Oleksyk and Martinez-Cruzado run LGDS.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.