Chlamydia Infections May Increase Cancer Risk

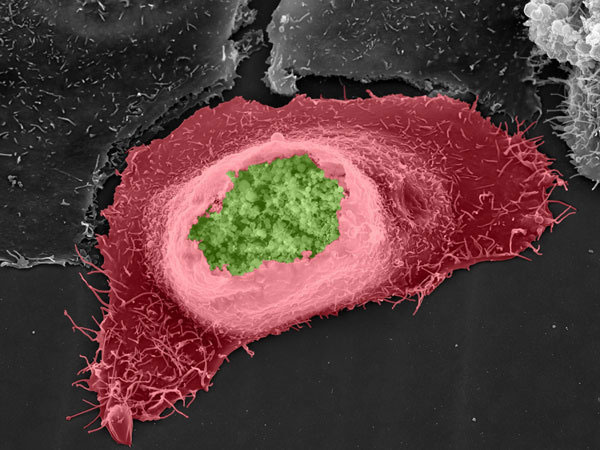

Chlamydia infections can cause DNA damage that may increase the risk of later developing cancer, a new study suggests.

In the study, human cells growing in lab dishes that were infected with chlamydia were more likely to have DNA damage compared to cells not infected with chlamydia. What's more, this DNA damage was not always repaired properly by the cell, increasing the chances of genetic mutations.

Normally, cells with such DNA damage would activate a process that kills the cells, so that the cell does not turn cancerous. But in the study, the cells with DNA damage overrode this mechanism, and continued to divide. The continued division of cells with DNA mutations could eventually lead to cancer, the researchers said.

Earlier studies found an association between chlamydia infections and an increased risk of cervical and ovarian cancer in people, but such studies cannot prove cause and effect. The new study provides a biological explanation for how chlamydia could increase the risk of cancer.

However, because the study was conducted in cells in a lab dish, more research is needed to show the same thing occurs in people.

The new study, conducted by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin, was published June 12 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. Most infected people have no symptoms, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, untreated infections can damage the reproductive tract in women, and cause infertility. Complications from untreated infections are rare in men, but the condition can cause a burning sensation when urinating, and very rarely, prevent a man from fathering children, the CDC says.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.