'Reverse Vaccine' May Fight Type 1 Diabetes

A "reverse vaccine" is showing promise in protecting the insulin-producing cells in people with Type I diabetes, researchers said after an early clinical trial.

The treatment, known as TOL-3021, uses a circular piece of DNA and is designed to deplete the body of antibodies that would otherwise attack the cells that produce insulin. Type 1 diabetes is brought about by this attack, which leaves the body without a way to produce insulin.

In the study of 80 patients, the number of insulin-producing cells was maintained over a 12-week regimen, and the levels of a byproduct of insulin remained the same or increased, depending on dosage.

The treatment is being dubbed a "reverse vaccine" because, in essence, it works the opposite way vaccines work; vaccinations turn on specific aspects of the immune system, while TOL-3021 turns off part of the immune system.

"[In this] new approach, called the reverse vaccine, we want to turn off just that part of the immune system that is attacking the pancreas, and leave the rest of the immune system intact," said Dr. Lawrence Steinman, a professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford University and a stakeholder in Tolerion Inc., which is testing the compound.

Steinman said that some treatments for diabetes have included drugs repurposed from other uses, such as organ transplantation, and they compromise the immune system. But because of the nature of the immune system's function in diabetes, a more-targeted approach would be more appropriate.

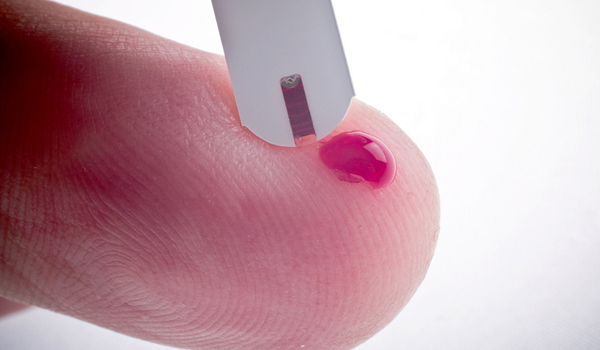

Patients in the study received either intramuscular injections of TOL-3021 or a placebo. Four different dosages of the drug were used, and placebo patients later received the drug as well. [11 Surprising Facts About Placebos]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ultimately, the 1-milligram dose — the second-smallest of the four studied — seemed to give the best response in terms of continued insulin production. All doses limited the number of cells attacking the beta cells.

"It certainly is somewhat positive, and I think is worth continuing in a bigger study to see whether it has any prolonged effects," said Dr. George King, the chief scientific officer of the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, who was not involved with the study.

One finding of the new study was that once patients stopped injections, the body's insulin-production capabilities appeared to drop again, so the treatment's effect was not permanent.

"From this data, I would say you have to try this much earlier, and it has to be continuous, so the question is, how do you do that?" King said.

Steinman said that while anyone with some surviving beta cells could be a candidate for treatment with the reverse vaccine, ideally, the treatment would be given as soon as possible after diagnosis.

The basic operating principle of TOL-3021 — targeting antibodies to ward off an immune system's attack on the body's own tissues — could be used in future, redesigned versions of the treatment, to combat other autoimmune diseases, the researchers said. Grave's disease, myasthenia gravis and neuromyelitis optica are all autoimmune diseases where the problematic, targeted cells are known.

Redesigning the drug for treating other conditions — such as rheumatoid arthritis or multiple sclerosis, where it is less clear exactly which immune system cells should be turned off — would be more difficult, Steinman said.

But diabetes researchers are hopeful for the success of the new treatment.

"New immunotherapies are required to control the autoimmunity associated with Type 1 diabetes, in order to preserve beta cell function in those at-risk of developing the disease, individuals who are newly diagnosed, and individuals with established disease," said Dr. Richard Insel, chief scientific officer at JDRF (formerly the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation), an early funder of the research for TOL-3021.

"Further clinical trials with this vaccine are required to explore effects of longer dosing periods, durability of effects and determination of the ideal target population," Insel said.

The study is published today (June 26) in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

FollowLiveScience @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com .