A 125-million-year-old fossil flea has been unearthed in China.

The ancient parasite, described today (June 27) in the journal Current Biology, had a mouth and body smaller than older fleas, but larger than modern-day pests. The new species, Saurophthyrus exquisitus, may be a transitional species that could shed light on why modern-day bloodsucking parasites evolved to become smaller and take dainty, unobtrusive bites.

Ancient pests

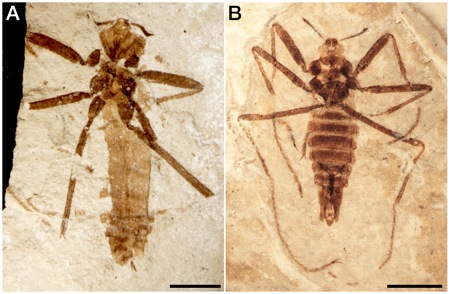

Last year, Chungkun Shih, a visting professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing, and his colleagues discovered the oldest known flea. The ancient parasites, known as Pseudopulicidae, were unearthed in 165-million-year-old sediments in northeastern China.

Pseudopulicidae had huge, 0.8 inch-long (2 centimeters) bodies with long tubes for sucking blood and sharp, sawlike teeth. The males also had completely external genitalia. Those ancient pests likely fed on the blood of thick-skinned, feathered dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic Period. [Dinosaur Fleas! Photos of Paleo Pests]

"The flea needed to cut through the thick skin to get to the blood, and they could do that harm without the host knowing it," Shih told LiveScience.

By contrast, modern-day fleas have bodies that are five to 10 times smaller, and have much smaller mouths, completely hidden genitals and longer legs for jumping.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In-between species

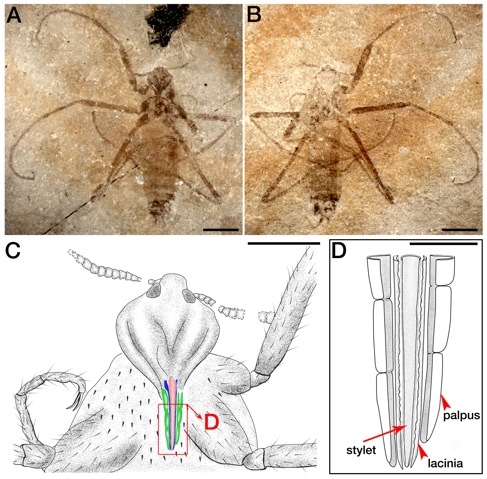

Shih and his colleagues were excavating in the same region when they uncovered three specimens of the new species, Sauropthyrus exquisitus. The ancient pest had a body size in between the oldest and modern-day fleas, growing up to 0.4 inches (1 cm) long. It also sported partially hidden genitalia, and a thin, relatively small sucking tube for drawing blood; it also lacked the fierce teeth of its older relative.

In addition, the new species had longer legs and short, stiff bristles on its body.

The researchers hypothesize that fleas originally evolved to feast on thick-skinned dinosaurs, so piercing the skin was the main challenge.

But as dinosaurs evolved, so did their parasites. The pterosaurs, or flying reptiles, that lived in the same region during that Cretaceous Era had much thinner skins. As a result, Sauropthyrus exquisitus adapted to deliver less painful bites, "so they would be harder to detect by the host," Shih said.

The bristles on its body may have helped the paleo pest cling to hairs on an animal's body to hide. And the longer legs and partially internal genitalia may also have enabled greater jumping ability, Shih said.

"You can imagine if you have something sticking out, it's hard to move around," Shih said, referring to the genitalia.

The new discovery suggests the parasites co-evolved with their hosts in a way to balance their bloodsucking and hiding abilities. Mammals have even thinner, more sensitive skin than pterosaurs, which makes the ability of fleas to take dainty, unobtrusive sips and jump away from a deadly swat especially important, Shih said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.