Climate change may transform the community of microbes that forms the crucial top layer of soil, known as a biocrust, in deserts throughout the United States, new research suggests.

The study, published today (June 27) in the journal Science, found that one type of bacteria dominates in warm climates, whereas another is more prevalent in cooler areas. Combined with climate models, the findings suggest that the cold-loving bacteria could completely disappear from their current habitats as the climate warms.

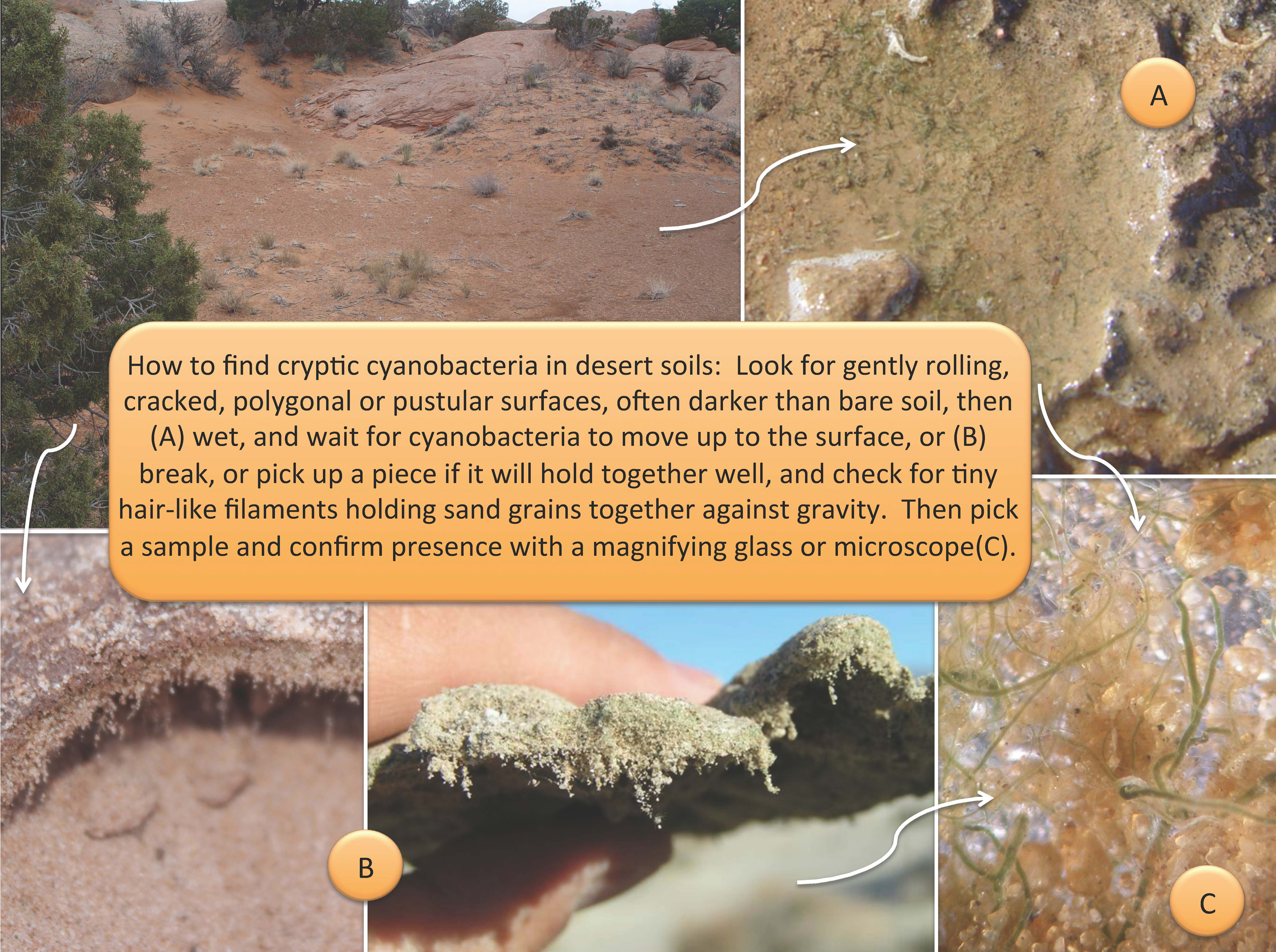

That disappearance, in turn, could have unpredictable ripple effects across the entire desert ecosystem, study researchers said, as the biocrusts are important resources for desert plants and help mitigate dust storms. [Photos: Mysterious World of Cryptobiotic Soils]

"For the first time, we have shown that the distribution of microbes is also prone to changes due to global warming," said study co-author Ferran Garcia-Pichel, a microbial ecologist at Arizona State University. "We simply don't know the consequences of this."

Ubiquitous organisms

Throughout the arid regions of the western United States, desert soil is permeated by a cryptic collection of photosynthetic organisms, including microbes, lichens and mosses. These mostly bacterial biocrusts anchor the soil, preventing sandstorms and erosion. They also play a critical role in cycling carbon and providing nitrogen in the soil, which feeds the growth of desert plants.

Yet these soils remained virtually unstudied by researchers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To get a better picture of these cryptic species, Garcia-Pichel and his colleagues conducted a thorough survey of the microbial constituents in biocrusts at 23 sites throughout the western United States. They found that two species — Microcoleus vaginatus and M. steenstrupii — each dominated in different regions.

Hot and cold

M. vaginatus predominated in cooler deserts near the California-Oregon border and in Utah, whereas M. steenstrupii was the main bacteria in the scorching deserts of Arizona, New Mexico and California. The researchers looked at several potential causes for the difference in distribution, such as rainfall and soil composition, but found that temperature was the best predictor of which microbe thrived in each region.

To help confirm that this was the major driver behind the distribution, the team then took the bacteria back to the lab and cultured them at different temperatures. Sure enough, M. steenstrupii flourished in warmer conditions and was more tolerant to extreme heat, while the opposite was true for M. vaginatus.

Next, they looked at global warming models, which predicted that the desert regions in the United States would increase in temperature over the next 50 years. With this projected warming, M. vaginatus could completely disappear from the arid regions of the western United States, the researchers said.

The team realized "this is enough temperature to push one of them out of our map,'" Garcia-Pichel told LiveScience.

Unknown consequences

Unfortunately, so little is known about the mysterious M. steenstrupii that no one is sure how this change will impact desert ecosystems, said Jayne Belnap, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Moab, Utah, who was not involved in the study.

"These are the only game in town to prevent dust storms and erosion, so they're really, really critical parts of this ecosystem," Belnap told LiveScience. "Yet we've never asked the question, 'who's really in there, and what's going to happen there as things shift?'"

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.