New Video-Analysis Software Sees Heartbeats

(ISNS) -- A new computer program can take someone's pulse without laying a finger on them. It analyzes videos of people trying to hold still and spots a tiny tic that betrays every heartbeat.

Not yet tested in a clinical setting, the algorithm could provide a way to check the health of newborns and elderly people with easily damaged skin. A camera feeding into the program could, in principle, monitor someone continuously.

Guha Balakrishnan, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate student who presented his team's project June 27 at the IEEE Computer Vision Pattern Recognition conference in Portland, Ore., didn't set out to study the heart. He planned to measure people's breathing rates by filming their heads moving up and down, in time with the expansion and contraction of their lungs. But then his videos revealed a subtle, intriguing spasm that occurred at regular intervals.

"I noticed it kind of by accident," said Balakrishnan.

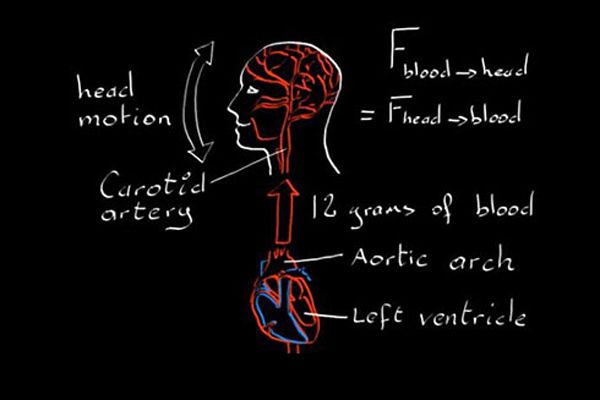

He had rediscovered a phenomenon known to medical science for more than 130 years. Every time the heart squeezes, the body jumps up. That's because blood rushing up out of the heart is channeled downward by the aorta, as well as by the blood vessels it strikes in the head. Physics dictates that the downward forces must be counterbalanced by upward forces on the blood vessels. Thus the body -- and the head -- rise like a water-propelled rocket.

The first practical device to take a pulse by monitoring this tremor dates to 1936. Invented by American physician Isaac Starr, the ballistocardiograph looked like a bed. The twitches of a sprawled out patient rocked the bed back and forth.

Balakrishnan's 21st-century twist on the idea didn't require any lying down. Each user stared at a video camera for up to 90 seconds while doing their best not to move. Software tracked up to 1,000 points on the face and then weeded out especially slow or fast movements tied to breathing or involuntary adjustments the head makes to keep itself balanced and upright.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nailing down the motions caused by heart contractions took a mathematical technique developed more than century ago, called principal components analysis. It finds patterns in complicated data and is often used for face recognition algorithms. In this case, a computer program tried out different combinations of the tracked points and selected the one that moved rhythmically at the steadiest pace.

"Picking out such a small signal isn't trivial," said Ira Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, a computer scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle. "It's impressive."

Eighteen healthy volunteers had their pulses taken, both by video and by today's gold standard: the electrocardiograph, an instrument that detects electrical impulses generated by the heart. The new technique proved accurate to within a few beats per minute. For most of the subjects, it also did a reasonable job of measuring how long each beat lasted and detecting variability from beat to beat, which is thought to play a role in some health problems.

Altogether the performance was comparable to other video-based approaches under development at MIT and the University of California, Irvine. Teams at those universities look at color changes in the face to identify heartbeats. Their digital cameras spot a flush that accompanies each rush of blood to the head.

Balakrishnan ultimately hopes to combine color and motion for an even clearer signal. But the obvious next step for his proof-of-principle algorithm, said Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, will be demonstrating that it works out in the real world. Different lightning conditions or busy environments could mask the tiny movements. Training the algorithm to work on a freely moving head would be a step forward. So would testing it on people with health problems.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics. Devin Powell is a freelance science journalist based in Washington, D.C. His stories have appeared in Science, Science News, New Scientist, the Washington Post, Wired and many other outlets, including The Best American Science Writing 2012 anthology.