8 Strange Things Scientists Have Tasted

Inquiring Taste Buds Want to Know

Curiosity about the world drives scientists, and for many researchers, that thirst for knowledge extends to their palates. Early scientists included doctors who tasted urine for diabetes and explorers who ate new species. These days, technology brings researchers new taste extremes, such as billion-year-old water and deep-sea squid. Here are some of the strangest things people have tasted as part of their research.

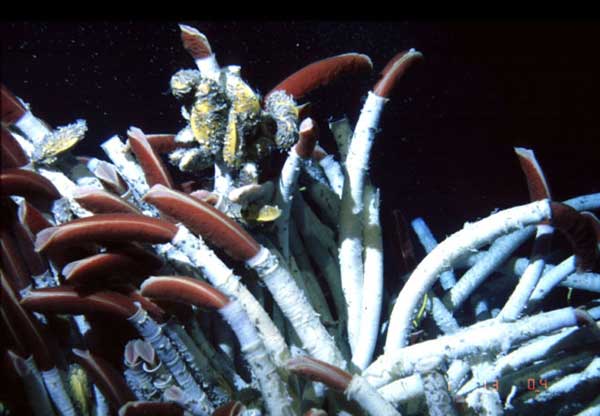

Ocean's delight

Eating their species of study is a rite of passage for marine biologists. Plankton soup, vampire squid and deep-sea tubeworms are some of the more unusual examples gathered by LiveScience. Scientists who work in the shallow ocean get tastier morsels, though, such as sea urchin gonads — the sushi delicacy called uni.

All the animals

Scientists in the 1800s didn't just eat their species of interest: They ate all the species. Charles Darwin is the most famous of these adventurous eaters. From his college days dining on brown owls to his worldwide travels trying tortoise and armadillo, Darwin devoured everything he encountered. Another audacious eater from this era is William Buckland, who is said to have eaten mouse, mole and the preserved heart of King Louis XIV. Buckland was a geologist and paleontologist who described the first full dinosaur fossil, the Megalosaurus.

Creepy-crawlies

Eating insects isn't strange in and of itself. They're great sources of protein, and many non-Western cultures create tasty dishes with bugs and grubs. But some entomologists take eating bugs a step further, for shock and awe (and in the name of science). For instance, many scientists often snack on non-food species, such as corn borers, in an attempt to convince undergraduates (or journalists) to eat bugs.

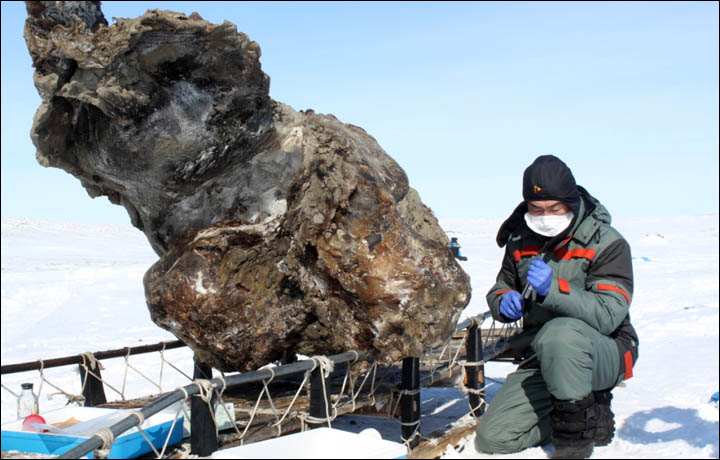

Steppe jerky

The stories of scientists eating mammoth go back more than 100 years, but are more legend than truth. That's because the animals emerge from their icy tombs as stinky, freezer-burned jerky, thanks to pre-freeze decomposition and thousands of years of thawing cycles.

However, one confirmed tale comes from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Paleontologist Dale Guthrie and colleagues, who excavated a 36,000-year-old steppe bison carcass called Blue Babe, stewed and ate extra neck tissue while prepping the bison for display. The meat was tough and had a strong "Pleistocene" aroma, Guthrie wrote in the book "Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe" (University of Chicago Press, 1989).

Ancient ice

The polar scientists are another group with a long tradition of imbibing their research. Out on the ice caps, there's no freshwater except for what's trucked or flown in. Melting ice provided a good source of drinking or washing water for generations of explorers. The advent of ice coring, to get a record of past climate preserved in older ice, meant scientists could really taste the past. Pieces of broken ice cores, not needed for research, became ancient ice cubes. Other circular cores were fashioned into drinking cups. Za vas!

Oldest water

The oldest ice on Earth is pretty tasty, because it lost its impurities through squeezing. But the oldest water on Earth tastes terrible, Barbara Sherwood Lollar told The Los Angeles Times in an interview. Lollar and her colleagues discovered the 2.6-billion-year-old water in a mine beneath Earth's surface in Ontario, Canada. The water pocket is 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) deep and full of minerals from the surrounding rock, such as iron and salt. It's also more viscous than tap water, she said.

Self-testing

Self-infection is the pinnacle of ingesting your research. Australian Barry Marshall drank a culture containing H. pylori to prove the bacteria cause stomach ulcers. The theory had been ridiculed, but Marshall's developing stomach ulcer was the first stepping-stone toward proving the link. He later won the 2005 Nobel Prize in medicine with long-time collaborator Robin Warren for discovering the link between H. pylori and peptic ulcer disease.

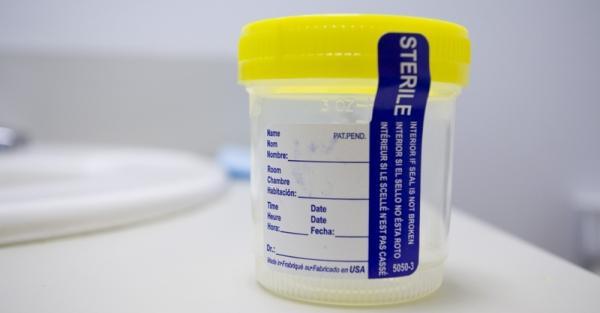

My diagnosis is ...

While early healers often missed the mark on diagnosing disease, due to lack of knowledge and understanding of the body, diabetes is one illness they could catch with a taste test. The only problem is the examiner, someone called a "water taster," had to drink the patient's pee. People with diabetes produce sweet-tasting urine. That's the origin of the name diabetes mellitus — mellitus is the Latin word for honey. Along with symptoms such as frequent urination and weight loss, sugary pee was a clue that helped lead scientists down the road to discovering insulin.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.