Chimp Genetic History Stranger Than Humans'

The most comprehensive catalog of great-ape genome diversity to date offers insight into primate evolution, revealing chimpanzees have a much more complex genetic history than humans.

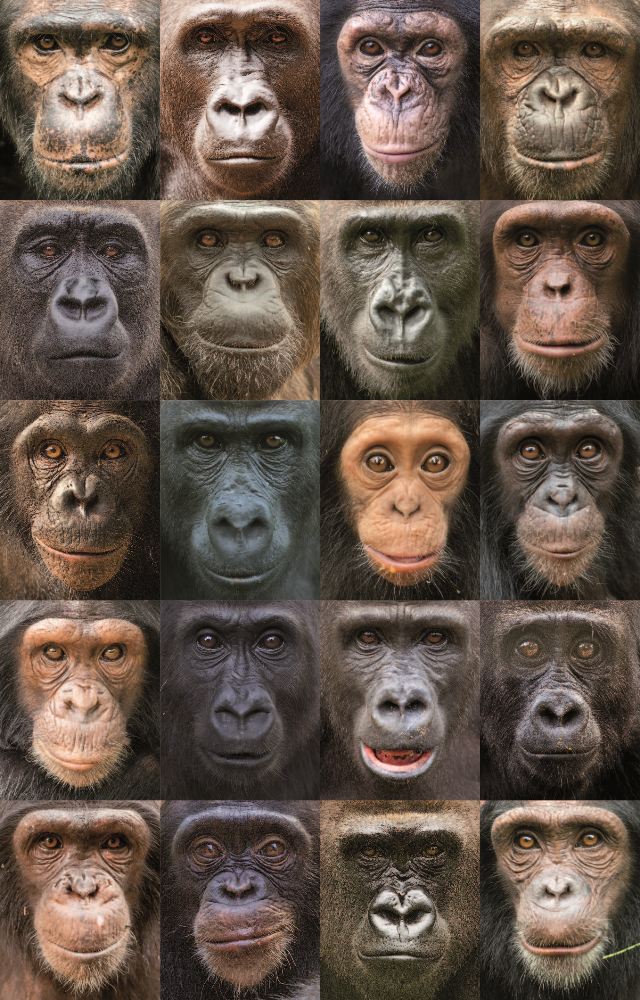

In a new study, researchers sequenced a total of 79 great apes, including chimpanzees, bonobos, eastern and western gorillas, orangutans and humans, as well as seven ape subspecies. The animals were wild- and captive-born individuals from populations in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Much attention has been focused on studying the diversity among human genomes, said study researcher Tomas Marques-Bonet, a geneticist at the Institut de Biologia Evolutiva in Spain. "If we want to understand the genetic diversity of humans, we need to measure the genetic diversity of our nearest relatives," Marques-Bonet said. [Unraveling the Human Genome: 6 Molecular Milestones]

As part of the study, Marques-Bonet and his colleagues were looking for genetic markers corresponding to changes in a single letter in the genetic code that define a subspecies. The researchers identified millions of such markers, which are important for conservation efforts. For instance, these markers allow people who manage wild-ape populations to identify different kinds of ape. Most of these animals are captured from illegal trade, so scientists don't know how they're related, Marques-Bonet told LiveScience.

Surprisingly, Marques-Bonet said, the genetic history of chimpanzees turned out to be much more complex than that of humans. Compared with chimps, "it looks like our [humans'] history has been really simple," Marques-Bonet said. Human populations encountered a bottleneck when they left Africa, and have since expanded to colonize the whole planet. By contrast, chimpanzee populations have undergone at least two to three bottlenecks and expansions, Marques-Bonet said.

The findings, the researchers said, also settle a hot debate over the relationships among the four chimpanzee subspecies — Central chimpanzee, Western chimpanzee, Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee and Eastern chimpanzee. "Now, we have the full genome for all four," Marques-Bonet said. Rather than revealing four groups, the sequences show that all chimps divide into two major groups: a Nigeria-Cameroon/Western population and a Central/Eastern population.

The new findings don't change humans' position in the great-ape evolutionary tree. Chimpanzees and bonobos are still humans' closest living relatives, splitting off from humanity about 5 million years ago. Humans' next-closest living relatives are gorillas, and orangutans are the most distantly related of the great apes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now, researchers can start tackling smaller-scale questions, such as distinguishing the subspecies, Marques-Bonet said. [Cool Images of Great Ape Subspecies]

Despite the genetic similarity between humans and chimpanzees, the two species are clearly quite different. Some scientists had hypothesized that the differences stem from the "lost" parts of human genomes compared with chimp genomes. But the new study disproved that theory by showing that the lost parts were mostly nonfunctional.

So if it's not genetics, what makes humans different from their great-ape cousins? "If I knew, I would have the Nobel Prize," Marques-Bonet said.

"Having these genomes is like having a book," he added. "So far, we are only just reading the book. It's not the same as understanding it."

The findings are detailed online today (July 3) in the journal Nature.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.