Agriculture may have arisen simultaneously in many places throughout the Fertile Crescent, new research suggests.

Ancient mortars and grinding tools unearthed in a large mound in the Zagros Mountains of Iran reveal that people were grinding wheat and barley about 11,000 years ago.

The findings, detailed Thursday (July 4) in the journal Science, are part of a growing body of evidence suggesting that agriculture arose at multiple places throughout the Fertile Crescent, the region of the Middle East believed to be the cradle of civilization. [In Photos: Treasures of Mesopotamia]

"The thing that's most astounding is that it extends the Fertile Crescent much farther east for the early agricultural sites, which are dated to 11,500 to 11,000 years ago," said George Willcox, an archaeologist at the CNRS (National Center for Scientific Research) in France, who was not involved in the study.

Cradle of civilization

The agricultural revolution transformed human society. Most researchers believe the domestication of animals and grains allowed small bands of hunter-gatherers to rapidly expand their populations, settle down, build the first cities in Mesopotamia and develop advanced civilization.

In the 1950s, archaeologists unearthed evidence of early agriculture in Jericho, Israel, which led researchers to believe agriculture first arose in Israel and Jordan. Newer genetic evidence from wild and domestic plants in recent years points to multiple origins for agriculture, from Southwest Turkey to Iraq to Northern Syria. But archaeological evidence has been scarce.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But in 2009, Nicholas Conard, an archaeologist at the University of Tuebingen, and his colleagues unearthed a tell, or a large mound formed by continuous human settlement, at Chogha Golan in the Zagros Mountains of Eastern Iran. [See Photos from the Chogha Golan Excavation]

"The earthen buildings were often flattened or destroyed or rebuilt but in the same place," Willcox told LiveScience. "Each time they rebuilt, the floor level would go up so you get these deep stratigraphic levels of habitation."

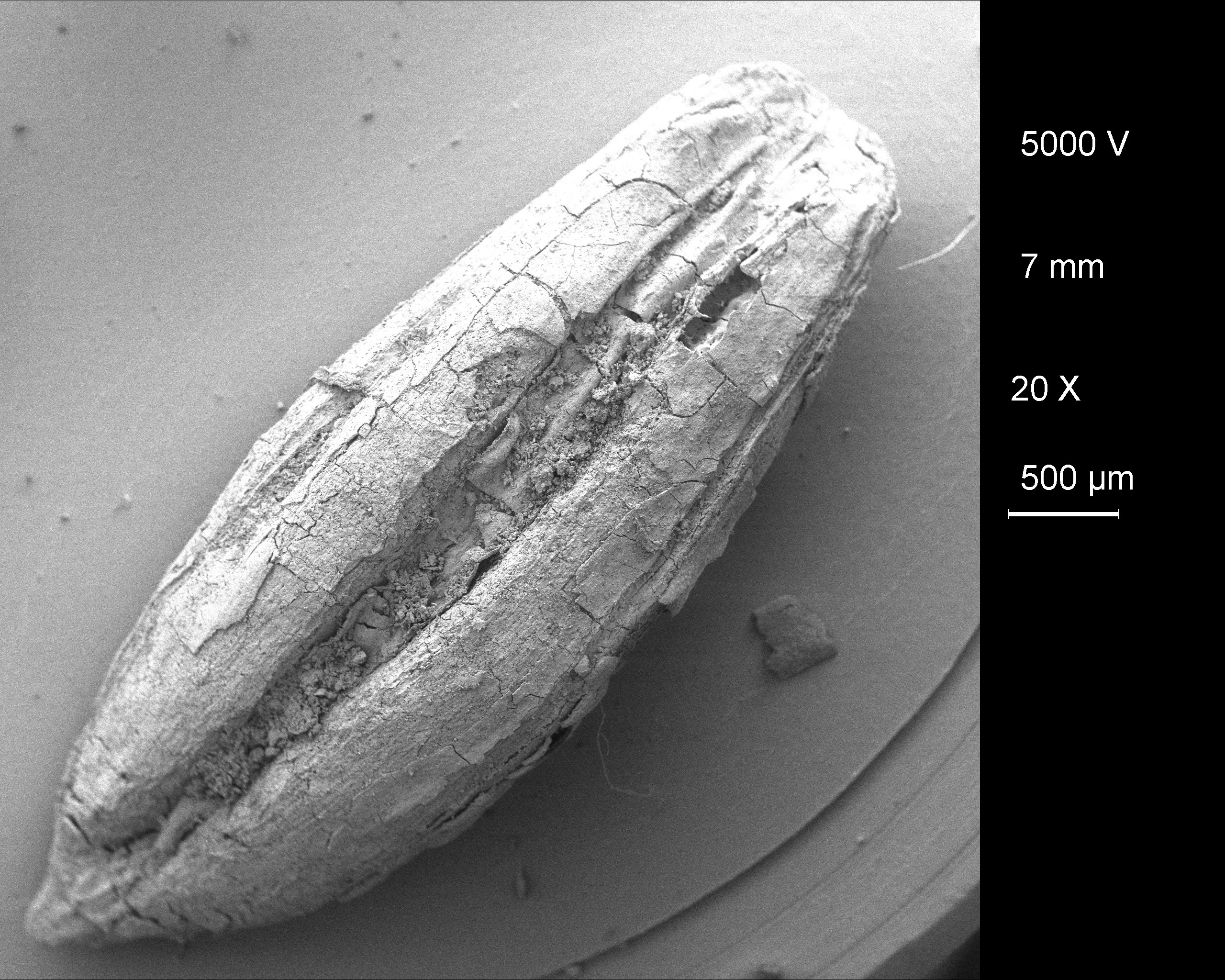

The site contained mortars and grinding tools, stone figurines and other tools, suggesting a large social group lived there under fairly stable economic conditions. The team also found thousands of examples of wild barley, wild wheat, lentil and grass pea remains throughout the site, some of the earliest evidence of agriculture in the world.

Based on levels of radioactive isotopes, or atoms of the same elements with different molecular weights, the team estimated that the site was occupied almost continuously between 9,800 and 12,000 years ago.

During early periods, humans were simply gathering wild plants, but evidence for domestication of wild strains of grains such as wild barley and lentils gradually emerge in the middle layers of the tell. By the end of the period, people had begun cultivating truly domesticated crops such as emmer, an early form of wheat.

Chogha Golan bolsters the notion that agriculture emerged at multiple sites, but exactly how that happened isn't clear, said Mark Nesbitt, an ethnobotanist and curator at Kew Gardens in London, who was not involved in the study.

"There are signs of contact and broad zones across the Fertile Crescent," Nesbitt told LiveScience.

For instance, obsidian from Turkey and shells from the Red and Mediterranean Seas are found throughout the Fertile Crescent, Willcox said.

So it's possible cultures had limited contact and spread agricultural technologies at around the same time period.

Another possibility is that agriculture emerged from one region further back in time and that crop cultivation is even older than these ancient human settlements suggest, Willcox said.

But so far, no trace of even earlier agriculture has been found.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.