A Natural Compass: Rock Cracks Point North

Night has fallen, and you are lost in the middle of an unfamiliar desert. There are ways to find your bearings by looking up at the stars. But how about looking down at the rocks?

According to Leslie McFadden of the University of New Mexico, there may be a kind of compass in the alignment of cracks in certain rocks.

In trying to explain how a boulder falls apart when water is scarce, McFadden has incorporated the power of the Sun, and the simple fact that it rises in East and sets in the West, roughly speaking.

"It dawned on me that Nature might exhibit the effect of solar heating by having cracks line up in a North-South direction," McFadden told LiveScience in a telephone interview.

McFadden and his colleagues have confirmed that a majority of cracks in some desert rocks are oriented in this non-random way. They go on to suggest that this weathering pattern could show up on other planets or moons.

Cracks in the pavement

McFadden's primary interest is weathering in the world's arid and semi-arid climates. One peculiar feature found in these dry areas is a desert pavement - a flat, gravel-strewn stretch of land, with little or no vegetation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They often have a dark color," McFadden said. "They almost look like a big parking lot."

Coalition forces trudged over desert pavements in Iraq, and the barren lots are common in the Southwestern United States. The thin layer of gravel that covers a pavement arises from the break down over millennia of the boulders that dot the landscape. How this weathering occurs has been a bit of a mystery.

Water can split a rock apart when it gets inside and freezes. But deserts generally do not get cold enough for this to happen, so geologists have speculated that salt weathering, in which salt grains form out of water that has penetrated into a rock, is the dominant action.

Salt weathering occurs along coastlines, where sea spray causes rocks to crumble apart. But McFadden does not think this process could fully explain the weathering seen on the desert pavements.

"To make salts work, you have to get salts into the interior of the rocks," he said.

McFadden and his colleagues contend that salt weathering is more effective at opening up cracks that are already there. To explain the initial splitting, the scientists have revisited an old idea that had previously fallen out of favor.

Hot rocks

Heat can be a significant factor in breaking down rocks. This is evident to anyone who has ever put a rock into a campfire or looked at the aftermath of a forest fire.

"When you have a fire, silicate rocks are broken down because they are inefficient conductors of heat," McFadden said.

Because of this poor conduction, the outside of a rock becomes extremely hot in a fire, while the inside can remain relatively cool. The temperature difference causes the rock to rupture, as the outer layers expand away from the interior.

Although there are not many fires out in the middle of the desert, there is the blazing heat of the Sun. Some dark rocks in the desert can reach 176 degrees Fahrenheit (80 degrees Celsius), according to McFadden.

In the 1930s, researchers looked at the effects of solar heating in the lab, but they could not reproduce the weathering seen in Nature, so the Sun was abandoned as an explanation.

The Sun is back

But desert cracks are a different breed. A split rock implies there was a strain between the two sides - a situation distinct from a fire, where the strain is between layers.

McFadden realized that the Sun, shining on only one side, could create such a strain due to the temperature differences. He said previous research had failed to take into account the rock's shadow.

"The largest surface temperature gradients will occur in the morning," McFadden said, when the shaded half of the rock is still cool from the night.

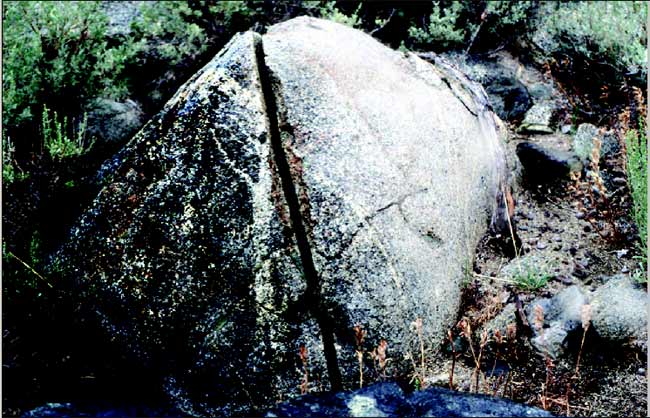

Therefore, if McFadden was right, the cracks should line up along the line between morning Sun and shade. On a relatively round rock, this line should point North-South. To test this hypothesis, McFadden and his colleagues went to a half dozen desert pavements in New Mexico, Arizona and California. They found that a majority of the cracks on round, uniform boulders lined up in a North-South direction.

"We have evidence that pulls the Sun back into the game," McFadden said.

The results were published in the current issue of the Geological Society of America Bulletin.

Not just rocks

The authors point out that solar heating could explain other kinds of weathering outside of desert pavements. Buildings and other man-made objects may form cracks that reflect the movement of light and shade across their walls.

And the effect may not be limited to our planet.

"There's a possibility that it might work on Mars where some signs of physical weathering have been seen," McFadden said.

Mars has a day that is only 40 minutes longer than Earth's. A similar heat-cooling cycle might explain the breakup of some of the rocks on the Red Planet.