Why the Southwest Keeps Seeing Droughts

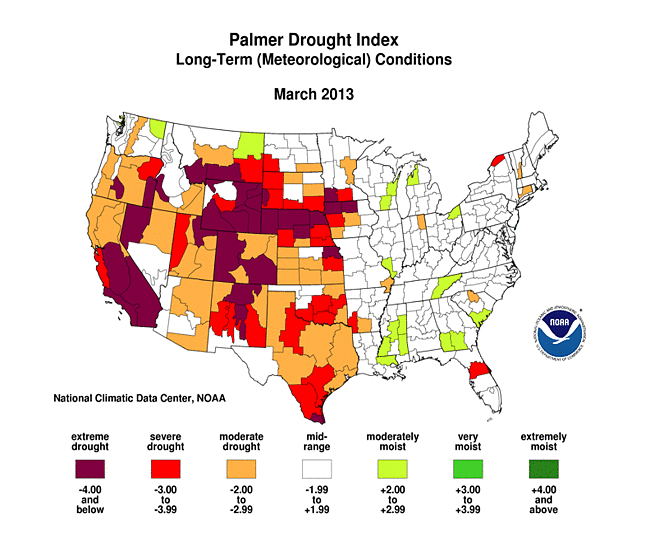

Severe drought parched the Southwest from Texas to California and heat waves set record-high temperatures. A New Mexico firestorm nearly killed 24 firefighters.

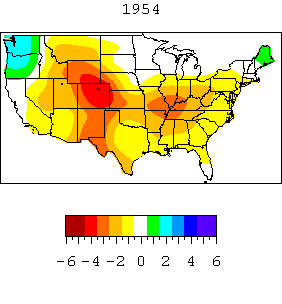

Sound familiar? Those were actually the events of 1950 in America, not 2013. In that year, natural cycles in Pacific and Atlantic oceans' sea-surface temperatures combined to create extreme heat and drought across the United States. And the pattern is repeating.

About 10 years ago, the two ocean patterns flipped into the same drought-causing phase as in the 1950s. Because of the change, climate scientists have predicted drier-than-normal conditions in the Southwest for the next 20 to 30 years. But this time, unlike in the 1950s, the climate patterns are getting a boost from global warming, making the heat and drought more extreme.

"The Atlantic and the Pacific were in a good state to promote drought in the 1950s," said Richard Seager of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York. "They've now gone back to the same phase. Because there is this background global warming signal, it is easier and easier to go past these temperature records, especially in the West."

Just last month, a heat wave in the Southwest and Alaska blasted away many of the high temperature records set in the 1950s. Water reservoir supplies are low this year because of minimal mountain snowfall in Colorado and Arizona. Last year, New Mexico set a new record for the largest fire in the state's recorded history. (The state's 1950 fire gave Americans Smoky the Bear, a cub who was burned in the blaze.) [The 8 Hottest Places on Earth]

"Climate change is making what would have been bad droughts even worse," Seager told LiveScience.

Oceans and drought

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

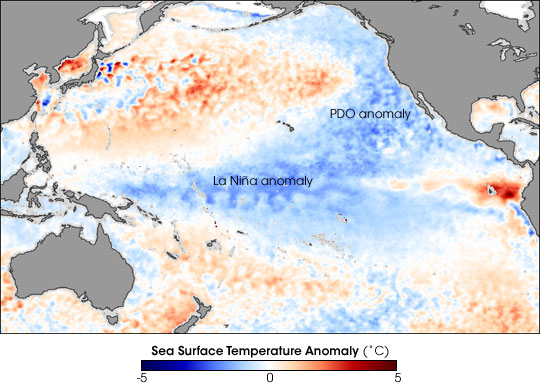

The two cycles, called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), flip back and forth between boosting rainfall and causing drought in the Southwest, among other effects felt throughout the continent.

Only discovered in the past two decades, these climate patterns have caused periodic, long-term Southwest drought going back more than 1,000 years, according to tree-ring records. More than half (52 percent) of the long-term drought in the lower 48 states can be attributed to the PDO and the AMO, according to a 2004 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The PDO perturbs sea-surface temperatures in the northeastern and tropical Pacific Ocean. The PDO switches between warmer and colder phases about every 20 to 30 years. The cycle was warm from 1925 to 1946, cool between 1947 and 1976, then rocked back to warm from 1997 to 1998. A colder PDO, as in the 1950s and today, is linked to drought in the Southwest and the Plains, but more rain and snow in the Pacific Northwest.

The PDO influences the same pool of tropical water that spawns the El Niño-La Niña cycle, the climate pattern with a huge global effect on precipitation, hurricanes and drought. Researchers think the two cycles give each other a boost. The warm PDO combines with the El Niño for wetter-than-average years, and a cold PDO plus a La Niña results in drier years.

"The 1950s drought was forced by multiyear La Niña conditions," Seager said. "And whenever it gets really dry, the surface and surface air temperature warms up, which is why many of those temperature records were set during the droughts," he said.

On the other side of the country, the 40-year AMO plays a smaller role in the Southwest's drought, but may have helped dry out the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. The tropical Atlantic sea-surface temperatures were high in the 1930s and 1950s, as they are today. The potential for drought in the United States seems highest when the AMO is in a warm mode, studies show.

In addition to the PDO and AMO, there are other ocean cycles and currents that affect the United States, along with random atmospheric variability.

For example: "The drought that hit the central Plains and Midwest last summer was unrelated to the ocean," Seager said. That was just a random sequence of bad weather."

Drought and global warming

Scientists are still teasing out the complex interplay between each of these climate cycles and drought, as well as the added effects of global warming.

"Droughts are one of the situations where we think there's a distinct global warming effect that occurs," said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. [Dry and Drying: Image of Drought]

Global warming exacerbates drought by adding extra heat to the atmosphere. In the Southwest, when water is around, this extra heat can dissipate by evaporating water. But during droughts, all that added heat has nowhere to go but the ground and the air, raising temperatures and drying out plants.

"When global warming rears its head, these drying effects accumulate over time, making the drought more severe and more extreme," Trenberth said.

The five decades between 1950 to 2000 were the warmest in 600 years, according to the Assessment of Southwest Climate Change, an independent report similar to the global climate report prepared by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The report, published in 2012, predicts that temperatures in the Southwest may rise as much as 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) by 2100. Reduced snowfall and increased evaporation will lead to more drought, the report said.

A climate modeling study, published in the journal Science in 2007, by Seager projected 90 more years of Southwest drought due to human-induced climate change. Scientists with the National Center for Atmospheric Research also found the western United States could face significant drought this century, in a 2010 study using 22 climate models.

"We are pushing the system into uncharted territory," Seager said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.