NASA's Quest for Green Rocket Fuel Passes Big Test

For decades, NASA has relied on an efficient but highly toxic fuel known as hydrazine to power satellites and manned spacecraft. Now the agency is laying the groundwork to replace that propellant with a safer, cleaner alternative.

NASA's Green Propellant Infusion Mission, or GPIM, has passed its first thruster pulsing test, a major milestone that paves the way for a planned test flight in 2015, agency officials said. NASA unveiled the rocket thruster success Tuesday (July 9) in Washington, D.C., during a briefing with aerospace industry officials and Colorado Sen. Mark Udall (D-CO).

The GPIM initiative aims to demonstrate that a green fuel with nearly 50 percent better performance than hydrazine could power Earth-circling satellites and eventually deep space missions. [Images: Superfast Spacecraft Propulsion Concepts]

Hydrazine has powered satellites and manned spacecraft for years, but it is highly flammable and corrosive, making it dangerous and expensive to transport. Since the fuel can be extremely harmful if it is inhaled or touches the skin, it is handled by workers wearing inflatable suits.

The new rocket fuel, dubbed AF-M315E, is far more benign; it is stored in glass jars and has been described as less toxic than caffeine.

The propellant is an energetic ionic liquid that evaporates more slowly and requires more heat to ignite than hydrazine, making it more stable and much less flammable.Its main ingredient is hydroxyl ammonium nitrate, and when it burns, it gives off nontoxic gasses like water vapor, hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

Importantly, M315E is safe enough to be loaded into a spacecraft before it goes to the launch pad, which would cut the time and cost of ground processing for a vehicle headed for space.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In today's world you cannot and do not want to load a spacecraft with hydrazine and ship it," said Michael Gazarik, associate administrator for NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD).

Udall, a Democrat, said the new propellant will cause less harm to the environment, boost fuel efficiency and pave the way for more complex launches.

"I don't know what there isn't to like in there," he told reporters Tuesday.

A company based in Udall's home state, Ball Aerospace, has been working witha subcontractor Aerojet Rocketdyne and NASA scientists to develop a propulsion system that can handle the new environmentally friendly fuel. The project is getting support from NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate, a new office charged with injecting money intovital technologies the space agency needs to fulfill its deep-space exploration goals.

Ball and Aerojet officials said that they successfully completed a test of the new fuel using a 22 Newton, (5 pound force) thruster, achieving an 11-hour continuous burn. In the planned 2015 demonstration flight, this thruster would fire simultaneously with four smaller 1 Newton thrusters to maneuver in space, making orbit and altitude changes.

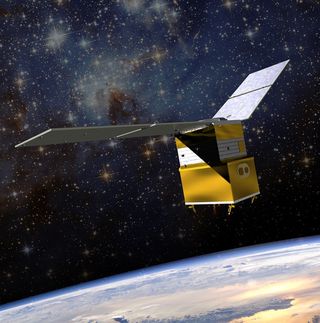

Right now, the team working on GPIM is in the preliminary design review phase. They hope to pass a critical design review by the end of the year, which would set the stage for the green propulsion system to launch in early 2015 aboard a fly aboard a boxy satellite, the Ball Configurable Platform 100 spacecraft bus.

NASA's GPIM budget is about $42.3 million, including a contract with Ball for approximately $35.3 million, according to a space agency spokesperson. Ball is developing the software to fly the spacecraft and the fundamental thruster technology is being provided by Aerojet Rocketdyne. The Edwards Air Force Research Laboratory, meanwhile, is contributing all propellant required for the mission.

M315E is just one new propulsion technology NASA is exploring to make its future missions more efficient. Some options wouldn't even require propellant fuel, such as solar sails that harness energy from the sun to send a vehicle through space.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.