Hold on to your wand, Harry Potter: Science has outdone even your best "Leviosa!" levitation spell.

Researchers report that they have levitated objects with sound waves, and moved those objects around in midair, according to a new study.

Scientists have used sound waves to suspend objects in midair for decades, but the new method, described today (July 15) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, goes a step further by allowing people to manipulate suspended objects without touching them.

This levitation technique could help create ultrapure chemical mixtures, without contamination, which could be useful for making stem cells or other biological materials.

Parlor trick

For more than a century, scientists have proposed the idea of using the pressure of sound waves to make objects float in the air. As sound waves travel, they produce changes in the air pressure — squishing some air molecules together and pushing others apart.

By placing an object at a certain point within a sound wave, it's possible to perfectly counteract the force of gravity with the force exerted by the sound wave, allowing an object to float in that spot.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In previous work on levitation systems, researchers had used transducers to produce sound waves, and reflectors to reflect the waves back, thus creating standing waves.

"A standing wave is like when you pluck the string of a guitar," said study co-author Daniele Foresti, a mechanical engineer at the ETH Zürich in Switzerland. "The string is moving up and down, but there are two points where it's fixed."

Using these standing waves, scientists levitated mice and small drops of liquid.

But then, the research got stuck.

Acoustic levitation seemed to be more of a parlor trick than a useful tool: It was only powerful enough to levitate relatively small objects; it couldn't levitate liquids without splitting them apart, and the objects couldn't be moved.

Levitating liquids

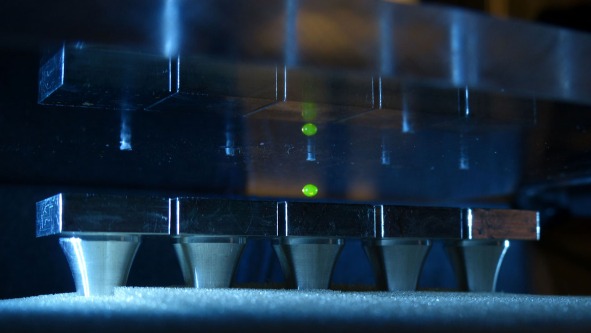

Foresti and his colleagues designed tiny transducers powerful enough to levitate objects but small enough to be packed closely together.

By slowly turning off one transducer just as its neighbor is ramping up, the new method creates a moving sweet spot for levitation, enabling the scientists to move an object in midair. Long, skinny objects can also be levitated.

The new system can lift heavy objects, and also provides enough control so that liquids can be mixed together without splitting into many tiny droplets, Foresti said. Everything can be controlled automatically.

The system blasts sounds waves at what would be an ear-splitting noise level of 160 decibels, about as loud as a jet taking off. Fortunately, the sound waves in the experiment operated at 24 kilohertz, just above the normal hearing range for humans.

However, "if you have some dogs around, they are not going to like it at all," Foresti told LiveScience.

Right now, the objects can only be moved along in one dimension, but the researchers hope to develop a system that can move objects in two dimensions, Foresti said.

Major advance

The new system is a major advance, both theoretically and in terms of its practical applications, said Yiannis Ventikos, a fluids researcher at the University College London who was not involved in the study.

The new method could be an alternative to using a pipette to mix fluids in instances when contamination is an issue, he added. For instance, acoustic levitation could enable researchers to marinate stem cells in certain precise chemical mixtures, without worrying about contamination from the pipette or the well tray used.

"The level of control you get is quite astounding," Ventikos said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Scientists built largest brain 'connectome' to date by having a lab mouse watch 'The Matrix' and 'Star Wars'

Archaeologists may have discovered the birthplace of Alexander the Great's grandmother

Elusive neutrinos' mass just got halved — and it could mean physicists are close to solving a major cosmic mystery