Huge Plant-Eating Dinosaur Never Ran Out of Teeth

Some plant-eating dinosaurs grew new teeth every couple of months, with some of the largest herbivores developing a replacement tooth every 35 days, to keep their chompers from getting too worn down on all that vegetation, new research finds.

A team of scientists studied the Diplodocus and Camarasaurus, two different types of long-necked, plant-eating dinosaurs, or sauropods, to determine if their diets may have influenced how often they developed new teeth. They found that Diplodocus, the longest dinosaur yet discovered, replaced their teeth fairly frequently — growing one new tooth every 35 days — while the Camarasaurus took nearly twice as long, about 62 days, to form a new tooth.

"Diplodocus and its relatives have the fastest tooth replacement rate of any dinosaur," said Michael D'Emic, lead author of the new study, and a paleontologist in the department of anatomical sciences at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, N.Y. [Paleo-Art: Dinosaurs Come to Life in Stunning Illustrations]

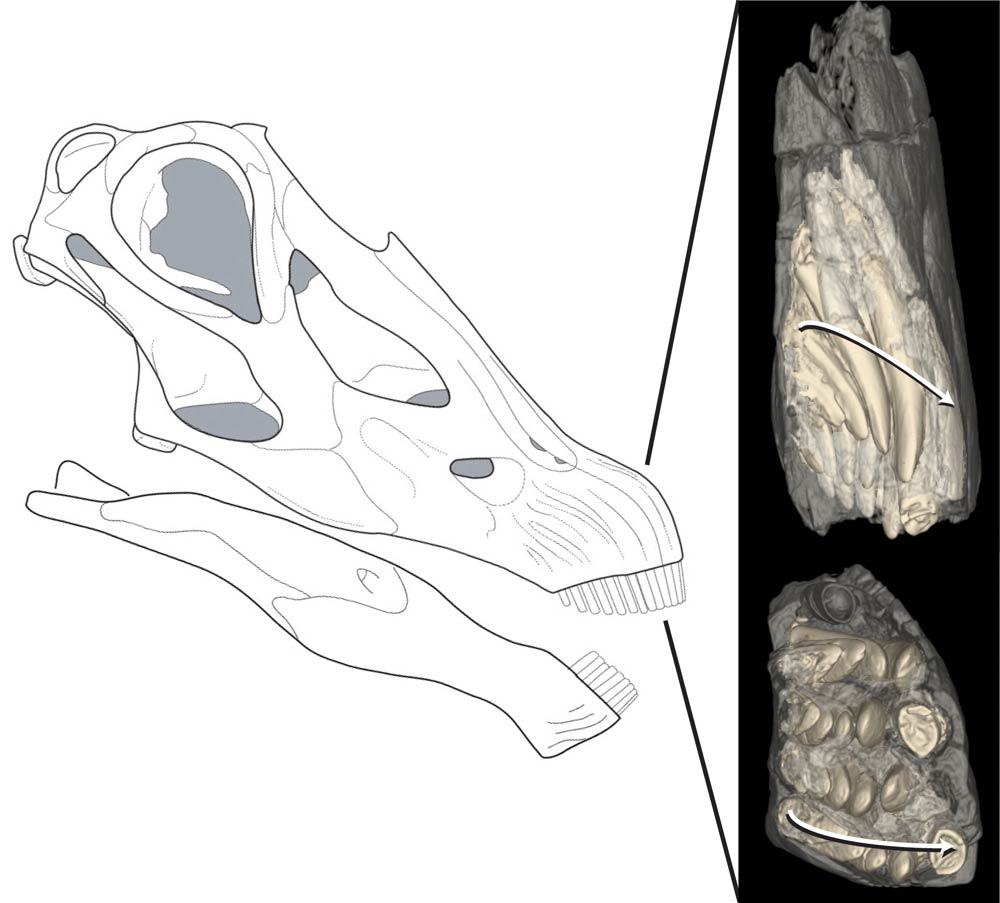

D'Emic and his colleagues also found that these plant-eating dinosaurs carried several spare teeth in their jaws.

"Some of these sauropod species have up to nine baby teeth in each socket waiting to take the old one's place," D'Emic told LiveScience. "It's pretty incredible."

Dino dental records

Each Diplodocus tooth socket held up to five replacement teeth, plus the functioning tooth, and the Camarasaurus could keep up to three spare "baby teeth" lined up in each of its tooth sockets, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

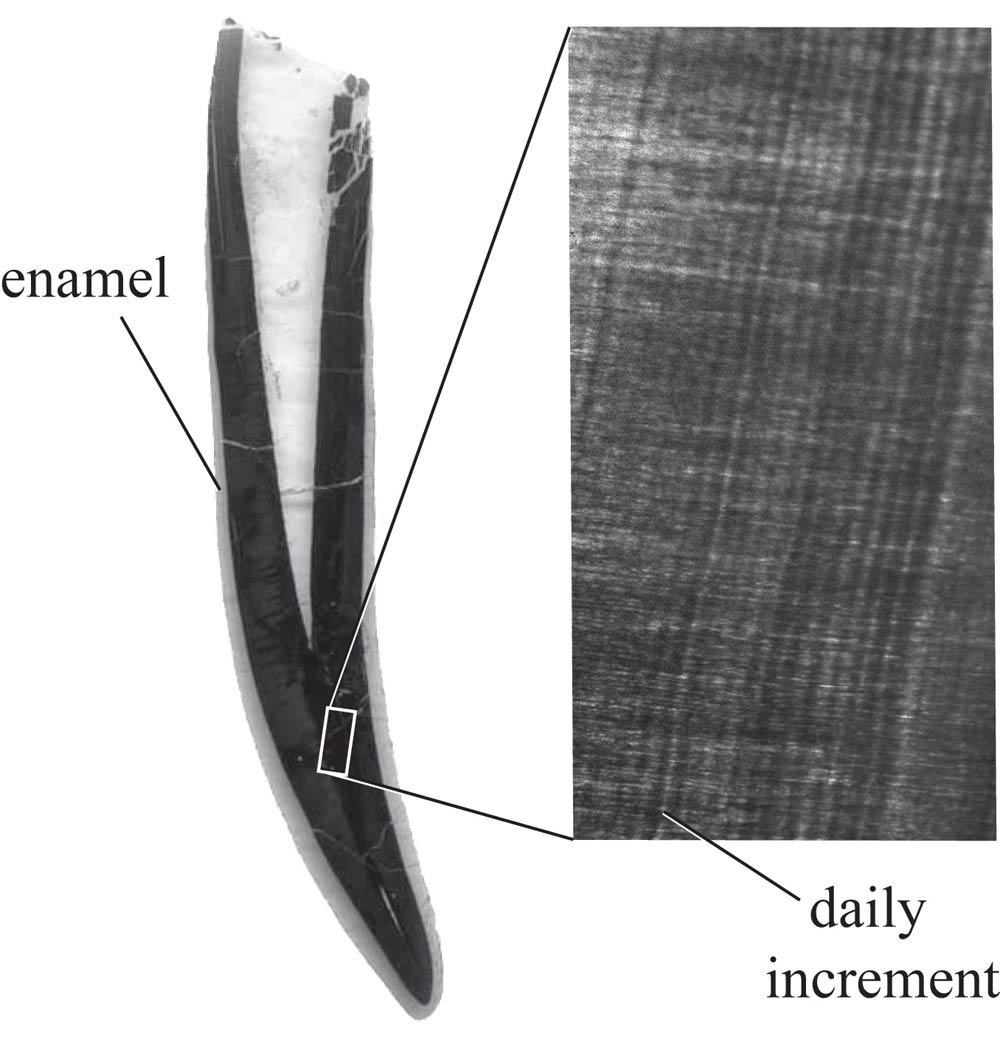

As teeth form, layers of a calcified tissue, called dentin, build up underneath a cap of enamel. "The bulk of the tooth is dentin, and this dentin is made day by day," D'Emic explained. "You end up getting something similar to tree rings, where each day there's going to be a ring in the tooth."

The researchers dissected fossilized teeth from both types of sauropods and examined thin slices of the teeth under a powerful microscope. This allowed the scientists to carefully study the tiny rings of dentin, which measure about a quarter of the width of a human hair, inside each tooth. These layers enable the scientists to tease out information about the rate of tooth formation and replacement in extinct animals.

Diplodocus and Camarasaurus both roamed the Earth about 150 million years ago, largely in regions within the modern-day western United States. Despite their long necks and giant bodies, these sauropods had small heads and tiny teeth. The dinosaurs typically had between 20 and 30 teeth in their upper and lower jaws, and these teeth likely experienced a lot of wear as the sauropods fed on the available vegetation, D'Emic said.

"Some of these animals were more than 90 feet [27 meters] long, and they had heads only a bit bigger than that of a horse, so that's a lot of food that has to go through there," he said. "To compensate for that, they must have evolved a response in which their tooth replacement rate increased."

Quantity over quality

Yet, compared to mammals today, these plant-eating dinosaurs developed teeth with thinner coats of enamel, which made them less hardy and resilient, the researchers said. This indicates that among herbivorous dinosaurs, the tooth replacement process had evolved to favor quantity over quality, the scientists said.

And while both the Diplodocus and Camarasaurus are sauropods, they are only distantly related to one another, the researchers said. This made them compelling case studies to study the effect of diet and ecology on the dinosaurs' teeth, D'Emic said.

"They both have long necks and long tails, but their heads are shaped differently, and they had different body postures," D'Emic said. "They also had very differently shaped teeth: The Camarasaurus had bigger teeth."

The differences in the dental records of the Diplodocus and Camarasaurus may indicate that the dinosaurs ate different types of vegetation. "It suggests they were eating different things, and that's probably one of the reasons they could have lived in the same place at the same time for so long," D'Emic said.

The paleontologists intend to expand their research by studying teeth from other dinosaur species, including meat-eaters. The detailed results of their new study were published online today (July 17) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.