Largest Viruses Ever Revealed

Giant viruses, more than twice as big as the last largest known viruses, have now been unearthed from sludge across the world, researchers say.

Even more titanic viruses might await discovery, the scientists said, and they may have features that could blur the lines between life and viruses, which are not considered to be living things.

Ten years ago, researchers accidentally discovered mimivirus, what until now was the biggest, most complex virus known. Mimivirus — a name derived from "mimicking microbes," chosen because the viruses were nearly the size of some bacteria — and its relatives the megaviruses can reach sizes of more than 700 nanometers (a nanometer is one billionth of a meter), and possess more than 1,000 genes, features typical of parasitic bacteria. Typical viruses are maybe 20 to 300 nanometers large, and many viruses, such as influenza or HIV, get along very well with 10 or fewer genes.

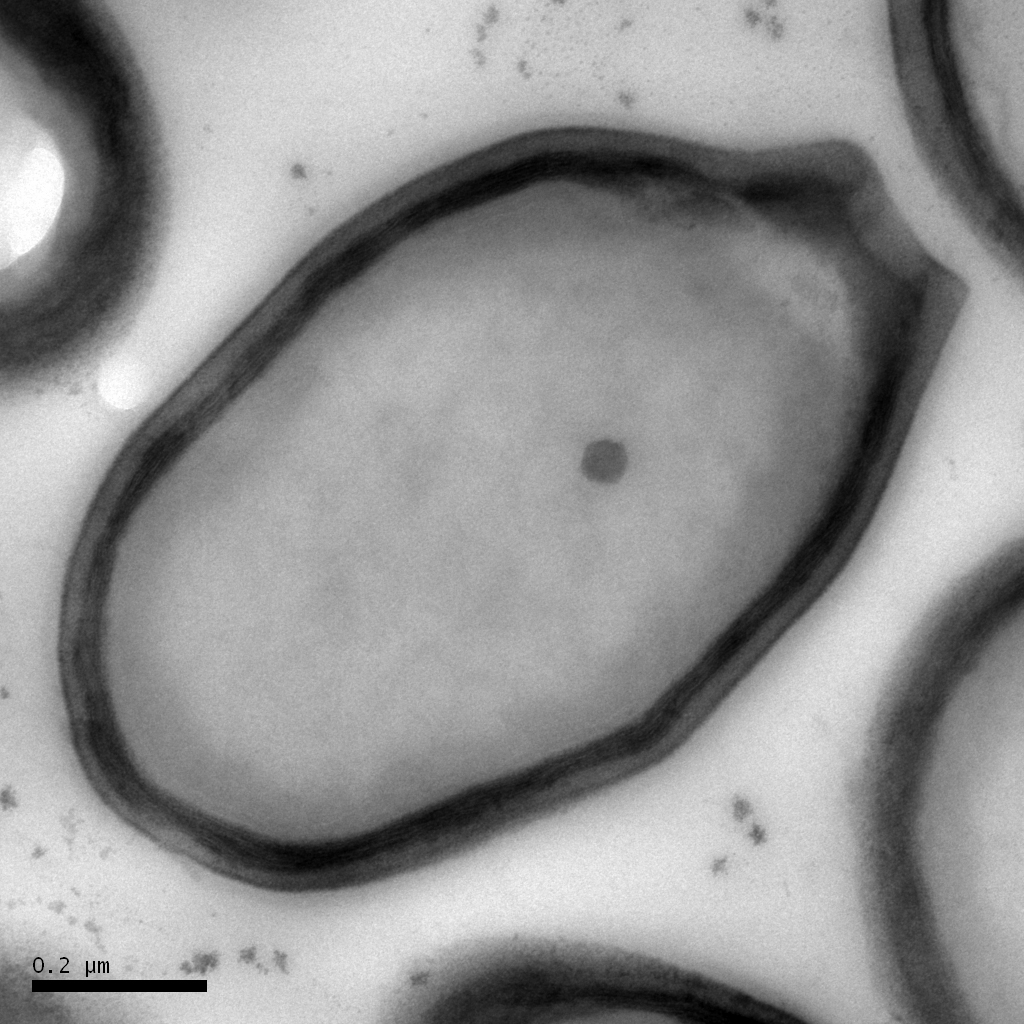

Now the research team that discovered those giant viruses have unearthed two more that are even bigger. The shape of these new viruses, which resemble ancient Greek jars, reminded the scientists of the myth of Pandora's box, giving the germs their name — pandoraviruses.

"The opening of the box will definitively break the foundations of what we thought viruses were," researcher Chantal Abergel, research director at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Marseille, told LiveScience.

The new record-breaking viruses are visible with a traditional light microscope, being a full micrometer or millionth of a meter in size, or approximately a hundredth the width of a human hair. They also each possess a whopping roughly 2,500 genes.

"We were prepared to find new viruses in the 1,000-gene range, but not to more than double that figure," Abergel said. "This really indicates than we don't know what are the possible limits anymore."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Megaviruses, which initially were mistaken for bacteria, were discovered in amoebas, and the investigators found pandoraviruses by also looking at amoebas. One virus, named Pandoravirus salinus, was unearthed at the mouth of the Tunquen River off the coast of central Chile, while the other, called Pandoravirus dulcis, dwelled at the bottom of a shallow freshwater pond near Melbourne, Australia. (Pandoravirus-like particles were actually first observed about 13 years ago, but were not recognized as viruses at the time.)

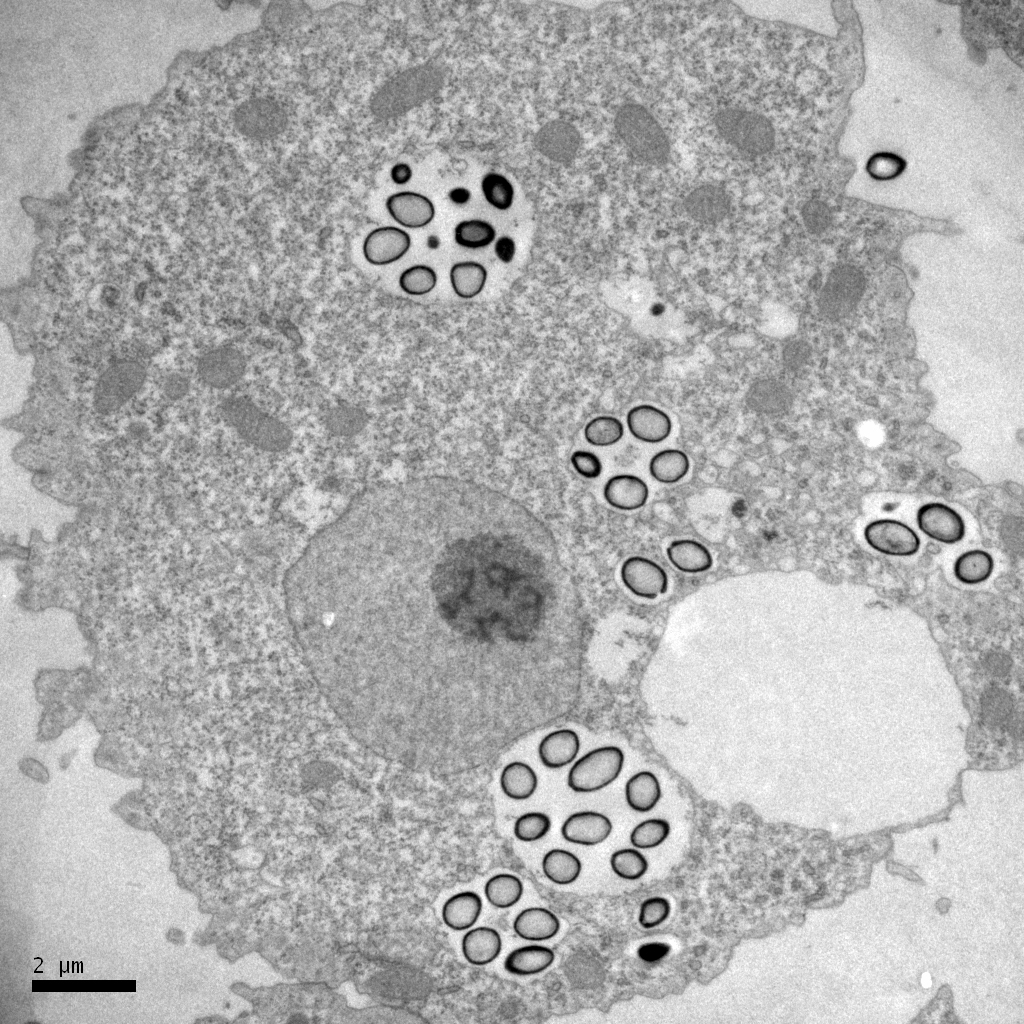

Two to four hours after amoebas engulf these pandoraviruses, the nucleus of the amoebas begins transforming radically, ultimately vanishing. When the amoebas finally die, they each unleash about 100 pandoraviruses. [Tiny Grandeur: Stunning Photos of the Very Small]

The amoebas the researchers used in their experiments are probably not the natural hosts for these viruses; rather, the main targets of these viruses may be protozoa or algae that are typically very difficult to grow and maintain in labs.

The scientists used amoebas instead because they can grow in labs, and gorge on their surroundings in a very indiscriminate way, sweeping most anything into themselves as they look for potential food. "This is why they are a very good target for capturing giant viruses," Abergel said.

More than 93 percent of pandoravirus genes resemble nothing known. This makes their origins a mystery — analysis of their genomes suggests pandoraviruses are not related to any known virus family.

"These viruses have more than 2,000 new genes coding for proteins and enzymes that do unknown things," Abergel said. "Elucidating their biochemical and regulatory functions might be of tremendous interest for biotech and biomedical applications. We want to propose a full large-scale functional genomics project on the pandoravirus genomes."

The fact that pandoraviruses are totally different from the previously known family of giant viruses may suggest even more families of giant viruses remain to be discovered, said researcher Jean-Michel Claverie, head of the Structural and Genomic Information Laboratory in Marseille, France.

"Our knowledge of the microbial biodiversity on this planet is still very partial," Claverie said. "Huge discoveries remain to be made at the most fundamental level that may change our present scenario about the origin of life and its evolution."

It remains a mystery why pandoraviruses have more than 2,500 genes while most viruseshave far less, the researchers said. One controversial suggestion the researchers make is that giant viruses and other viruses that depend on DNA as their genetic material may be the shrunken descendants of living, cellular ancestors.

"Parasites of any kind are submitted to the universal process of 'genome reduction' — that is, they may lose genes without harm, because the host can always provide the missing function," Claverie said. DNA viruses small and giant may all have degenerated from the same or similar cellular ancestors, "but only differ by the rate by which they lost genes from the starting ancestral genome," he said.

Future research could turn up "even more intermediary life forms between viruses and cells, establishing a continuity between the two," Abergel said. "How should we define the boundaries between cells and viruses?"

The scientists detailed their findings in the July 19 issue of the journal Science.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.