False Memories Implanted in Mice

Tinkering with the brains of mice, scientists have given the rodents memories of events that never occurred.

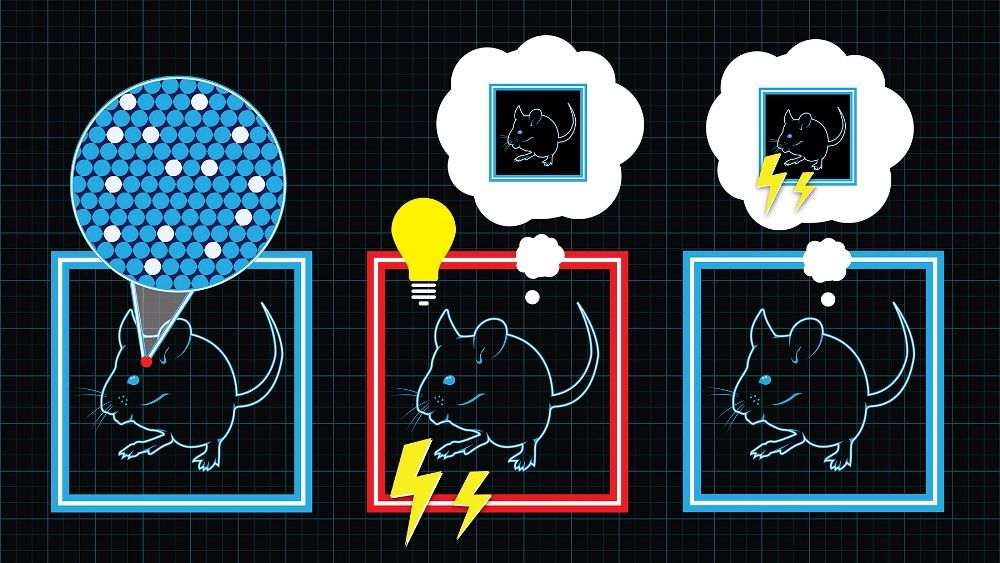

The researchers used a technique that involves activating neurons with light to train mice to "remember" a painful experience in a completely different context from that in which they experienced the pain. The false memories were encoded by brain cells in the same way as real memories are sealed in.

Even without any scientific manipulation, memories can be unreliable. Many studies have shown the limits of eyewitness testimony in the courtroom, for instance. But few studies have looked at how false memories are formed at the cellular level. [5 Wild Facts About Your Memory]

"In humans, false memory phenomena are very well established, and in some cases it can have had serious legal consequences," said study researcher Susumu Tonegawa, a neuroscientist at MIT in Cambridge, Mass.

When the brain forms a memory, a population of brain cells is thought to undergo lasting physical or chemical changes, creating what's called a "memory engram." Memory has two phases: First, the memory is acquired by activating these brain cells, and later it is recalled by reactivating these cells. Scientists had hypothesized, but never proved, these memory cells existed.

Implanting mice memories

Last year, Tonegawa and his colleagues showed that such cells do exist in a part of the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center. The researchers genetically engineered mice to make certain neurons light-sensitive — a technique known as optogenetics — so that shining a blue light on the cells activated them.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mice were put in a chamber where they experienced foot shocks, causing them to freeze in fear. The animals learned to associate the shocks with the chamber, forming a fear memory. Then the researchers put the mice in a different chamber, and shone a blue light on the cells that encoded the foot-shock memory. The animals reacted as fearfully as if they were in the first chamber.

In the present study, Tonegawa's group took the experiment a step further. First they allowed the mice to explore the first chamber without getting a foot shock. Then they put the mice in a second chamber where they gave them foot shocks while shining a blue light on the cells that encoded the memory of the first chamber. They wanted to see whether, when they put the mice back into the first chamber, they would react as if they had been shocked there.

The mice did exactly that, showing fear when they were placed in the first chamber, even though they had never experienced a shock there. The researchers had succeeded in implanting a false memory into the mice. The findings were detailed online today (July 25) in the journal Science.

"Memory comes from experience," Tonegawa told LiveScience. But in this case, the animal never experienced any fear in the first chamber, and yet the animal was fearful of that chamber, he said.

False human memory

The findings provide a model for how false memories might be formed in humans. Before the advent of DNA testing, many criminals were convicted primarily on the basis of eyewitness testimony. When their DNA was tested later, "three out of four people imprisoned for many years based primarily on witness recall turned out be innocent," Tonegawa said.

Tonegawa described the famous case of a woman who was watching TV when a man broke into her apartment and raped her. The man she accused as her rapist was a psychiatrist who had been on TV at the time she was raped. The psychiatrist was in a TV studio and therefore could not have been the rapist, and yet the woman swore it was him, because she had formed a false memory associating the sound of his voice with the rape.

"Like our mouse case, only the false memory prevailed," Tonegawa said.

So how could humans have evolved the ability to form false memories? Tonegawa speculates that false memory is the price humans pay for creativity. Our imagination makes us inventive, but it also makes us susceptible to conflating events that did and didn’t happen.

"Humans are very creative," he said. "As a byproduct, we form false memories."

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.