Weird Weather: Dry Seasons Start Earlier, Are Wetter

Call it weird, call it extreme, maybe even call it the new normal. Wild weather in the United States in the past decade has amassed a long list of toppled records and financial disasters.

Some of these exceptional weather events included unusually heavy rain and snow. Now, a new study confirms that everywhere except in the Atlantic Plains region, more rain and snow is falling during wet and dry seasons alike. The Atlantic Plains are the flatlands along the central and southern Atlantic Coast that stretch from Massachusetts to Mississippi. On average, the total precipitation in the contiguous United States has increased 5.9 percent, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

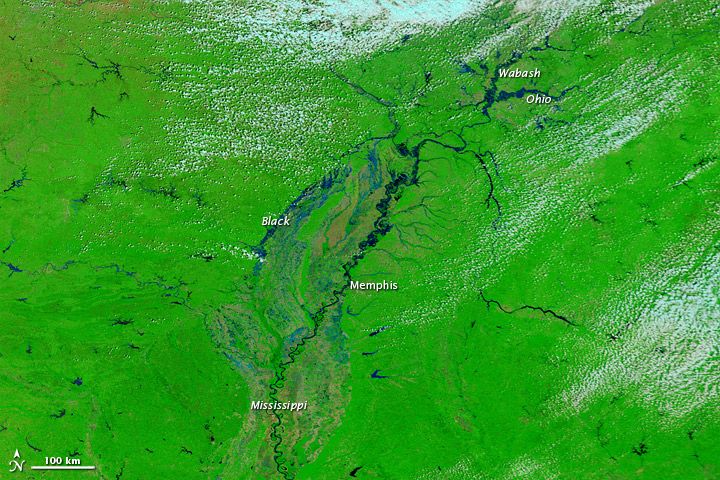

What's more, the timing has changed too. In some parts of the United States, dry seasons are arriving earlier and wet seasons are starting later than they did 80 years ago. The time shift does not necessarily extend the length of dry or wet seasons, because most areas have transitional periods in between these precipitation extremes. In the Ohio River Valley, the fall dry season starts two to three weeks earlier today, the researchers report. In east New York, the wet season now kicks off on Jan. 8 instead of Feb. 1. And in the Southwest, the summer monsoon is starting later than it did during the middle of the 20th century. [In Images: Extreme Weather Around the World]

"The effects vary from region to region," said Indrani Pal, lead study author and a water resources engineer at the University of Colorado in Denver. "This study has a lot of implications from an ecology and water management perspective, and for extreme events like droughts and floods as well."

Altering the timing of dry and wet season starts can significantly affect agriculture and cities, Pal said. In the Southwest, water contracts rely on the timing of spring snowmelt and summer monsoons to generate hydroelectric power and water for farming and millions of residents.

Pal and her colleagues analyzed data from 774 weather stations across the United States with a continuous record since 1930. They found an overall drop in dry spells (the number of days without precipitation) between 1930 and 2009 in most regions of the country. For instance, there were 15 more precipitation days (rain or snow) during the dry season in the Central and Great Plains, and 20 more precipitation days during the wet season in the Midwest and intermountain regions today than 80 years ago. However, the length of dry spells during the wet season, a drought indicator, increased by 50 percent in the Atlantic Plains.

Pal said the study cannot answer whether climate change is causing the seasonal shifts in precipitations. "This opens many other research doors," she told LiveScience. "We would like to find what is actually affecting this shift. It's probably a mixture of natural variability and climate change," Pal said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings were published July 19 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.