Martian Meteorites May Be Younger Than Thought, Studies Suggest

The riddle of the age of meteorites from Mars might now be solved, with researchers finding these rocks from the Red Planet might not be billions of years old as some studies have suggested.

The new findings shed light on when the Martian crust formed, suggesting the Red Planet has a relatively young, volcanic crust with an ancient, largely inactive, mantle layer below it, scientists added.

Meteorites from Mars occasionally crash land on Earth, and were likely blasted off the planet by cosmic impacts. Known Martian meteorites are very rare — only about 220 pounds (100 kilograms) have been found. [See photos of Mars meteorites found on Earth]

History of Mars

As samples of the Red Planet, Martian meteorites could, in theory, answer questions about the nature and history of that world, such as when the Martian crust they came from formed. However, attempts to glean knowledge from these rocks have been hampered by debates over how old they really are, with estimates varying tremendously; some put them at either less than 200 million years old or more than 4 billion years old.

Now scientists find both estimates might be right in a way. The building blocks for the crystals in these meteorites appear to be about 4 billion years old, but the crystals themselves are only about 200 million years old.

"Imagine a building — the age of the rocks that are put into the building might be 4 billion years old, but the building itself was erected 200 million years ago, and one generally judges a building's age by when it was raised, not how old its materials are," study author Kevin Chamberlain, a geochronologist at the University of Wyoming at Laramie, told SPACE.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

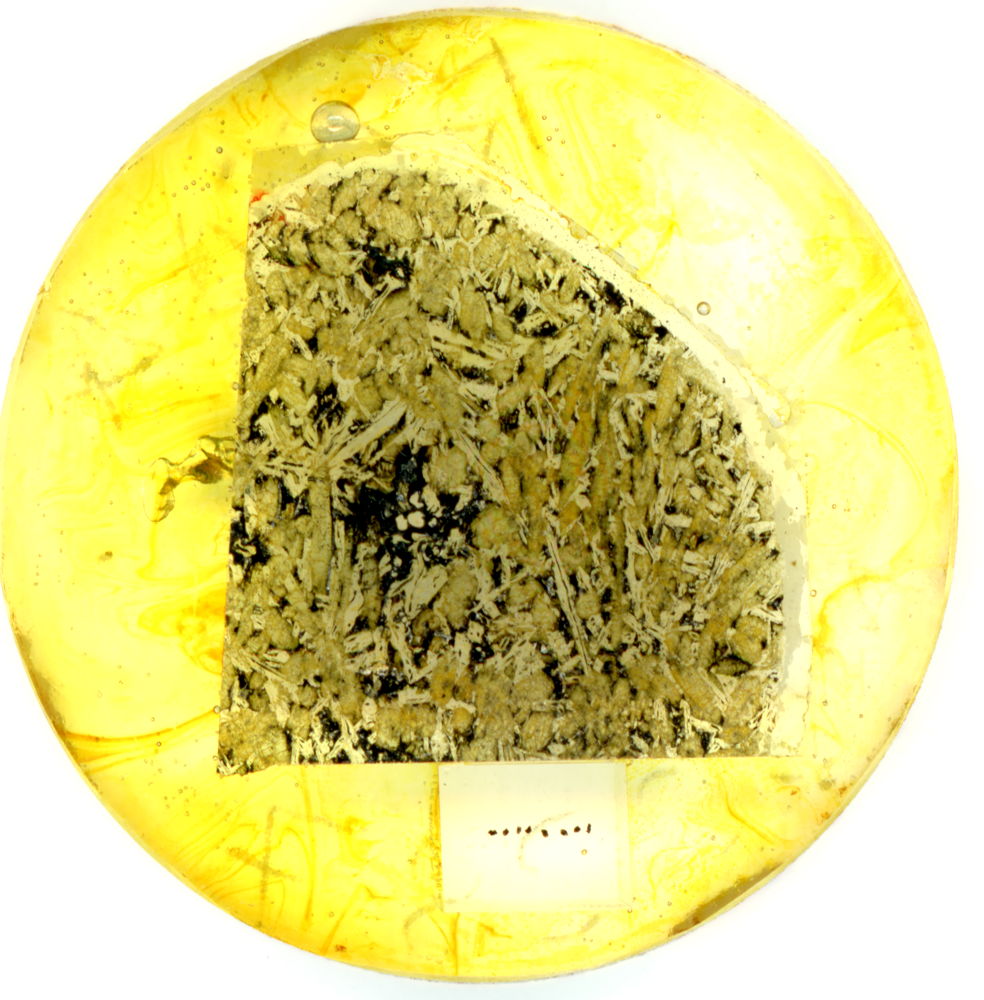

Scientists analyzed tiny crystals in the Martian meteorite NWA 5298, the fifth largest of all the known Martian meteorites. Discovered in northwest Africa in 2008, the 6.56-lbs (2.98-kilogram) rock currently resides in the Royal Ontario Museum's collection.

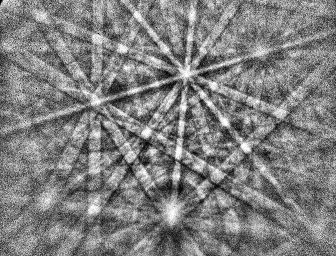

The researchers developed a way to analyze the age of a rock from pits just 1 micron deep and 20 microns wide in the sample. For comparison, the average diameter of a human hair is about 100 microns."From super-tiny samples, our analyses have implications on a planetary scale," Chamberlain said.

The investigators focused on the isotopes within these samples. The elements that make up planets and stars each come in a range of isotopes that vary depending on the number of neutrons in their nucleus — for instance, carbon-12 has six neutrons, while carbon-13 has seven. Radioactive isotopes decay over time, transforming into different elements, so by looking at the ratio of different elements within a sample — in this case, uranium and lead — researchers can deduce its age.

Martian minerals

The scientists also examined the structure of the minerals in the meteorite. The youngest part of the sample had a disordered structure, revealing it had experienced a great shock, most probably from the cosmic impact that blasted the meteorite off Mars in the first place. In contrast, the oldest part kept its crystalline structure.

Investigation of the oldest, unshocked portion of the meteorite showed it was 187 million years old. Analysis of the shocked part suggests it was launched at Earth about 22 million years ago.

The meteorite is made of volcanic rock known as basalt that likely came from the flanks of the supervolcanoes at the Martian equator.

"The 4-billion-year-old date determined before actually came from the source material that was melted in the volcanism that formed these minerals," Chamberlain explained. "Having evidence that Mars was geologically active fairly recently is a pretty big deal."

The researchers now plan to date "additional meteorites from Mars, the moon and several asteroids to gain a better understanding of the evolution of the solar system," Chamberlain said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the July 25 issue of the journal Nature.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.