The 10 Biggest Deserts on Earth

Big deserts

Earth is a planet covered with habitable areas, but some of those locations are a little more hostile to life than others. In deserts, which generally are defined as areas that receive less than 10 inches (254 millimeters) of rain or snow annually, the plants and animals must subsist on this meager precipitation.

The world's 10 biggest deserts are found on just about every continent, many of them forming in the shadow of immense mountain ranges that block moisture from nearby oceans or bodies of water. They're often the site of unusual rock formations and, in some cases, amazing archaeological finds.

Chihuahuan Desert

175,000 square miles (282,000 square km)

Straddling the U.S.-Mexico border, the Chihuahuan Desert is bigger than the state of California, according to New Mexico State University. Parts of it are in the states of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Less than 9 inches (228 mm) of rainfall falls on average every year, according to the Chihuahuan Desert Education Coalition.

As with many other deserts worldwide, the Chihuahuan Desert formed in the rain shadow of both the Sierre Madre Occidental (on the west) and the Sierra Madre Oriental (on the east), which both stop water from the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico from getting inland.

Underneath the desert and New Mexico's Guadalupe Mountains lies more than 300 caves. Those in at least one of those regions, Carlsbad Caverns National Park, were created after sulfuric acid penetrated the surrounding limestone.

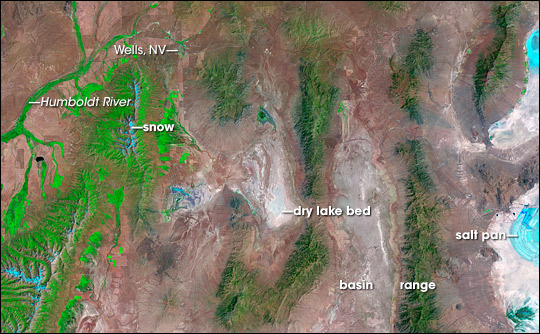

Great Basin Desert

190,000 square miles (492,000 square km)

Unlike every other desert in the United States, the Great Basin is a "cold" desert — one where most of the precipitation falls as snow. Its geographic extent includes most of Nevada, part of Utah and parts of many surrounding states. Rainfall in the region ranges between 6 and 12 inches (150 and 300 mm) annually.

The desert came to be because it was in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of eastern California, according to the National Park Service. The desert, in turn, also affects surrounding areas. Strong winds known as the Santa Ana often blow into Southern California after forming in areas of high pressure in the Great Basin.

The Great Basin is also home to some unusual rocks, such as some found in central Nevada in 2009 that were described as dripping like honey. The deformation is taking place due to changes in the Earth's mantle, which alters due to intense pressure and heat within Earth's surface. Heavier material in the lithosphere, as it warms up, sinks through the lighter mantle, trailing material after it.

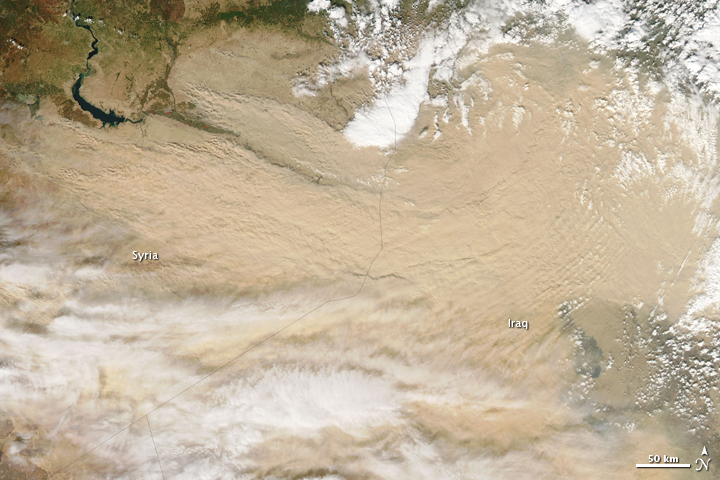

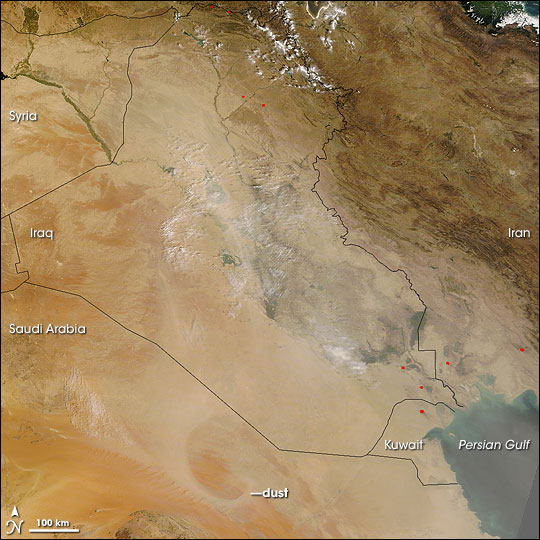

Syrian Desert

200,000 square miles (518,000 square km)

The Syrian Desert is described as an "arid wasteland" by Merriam-Webster. Covering much of Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Syria, the region is marked by lava flows and was an "impenetrable barrier" to humans until recent decades. Now, highways and oil pipelines cross the region, which receives less than 5 inches (125 mm) of rain annually, on average.

Humans were able to reach parts of it in ancient times, though. One area, now dubbed "Syria's Stonehenge," was discovered in 2009. It includes stone circles and possibly, tombs, according to a 2012 Discovery News report.

The Es Safa volcano field near Damascus is Arabia's largest volcanic field. The vents found in that area were active about 12,000 years ago, during the Holocene Epoch. More recently, a boiling lava lake was spotted in the region around 1850.

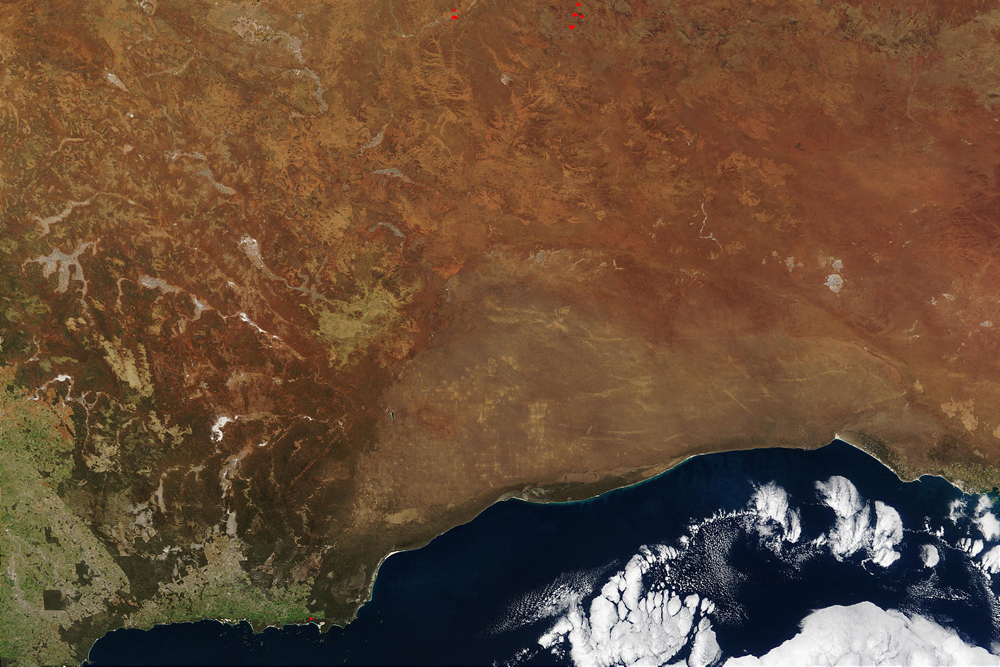

Great Victoria Desert

250,000 square miles (647,000 square km)

The Great Victoria Desert covers a great deal of Australia and is mostly made up of parallel dunes as well as some salt lakes, according to an atlas from the Government of South Australia. The dunes are mostly red sand that came from the Western Australian Shield, changing to white as one moves south due to sands coming from the coast.

The Australian government describes the region as one with "variable and unpredictable rainfall." Averaging out data between 1890 and 2005, rainfall is about 6.4 inches (162 mm) annually. Due to the harsh environment, most of the desert is split between Aboriginal lands, conservation areas and crown land, with no major cities.

One of the Outback's greatest ecological threats comes from camels, whose ancestors were imported from India, Afghanistan and Arabia during the 19th century for work in the desert. A 2013 BBC report said the approximately 750,000 feral camels drink an ordinate amount of water and also damage infrastructure. "Camels are almost uniquely brilliant at surviving the conditions in the Outback," said explorer Simon Reeve in the report. "Introducing them was short-term genius and long-term disaster."

Patagonian Desert

260,000 square miles (673,000 square km)

The Patagonian Desert is a large desert lying across much of Argentina. The desert and semi-desert area stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Andes, with mostly treeless plains, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Like California's Death Valley, the Patagonian Desert lies in the "rain shadow" of a high mountain range — in Patagonia's case, the Andes. Some regions of the desert receive as little as 6 to 8 inches (160 to 200 mm) of rainfall a year, according to Dryland Climatology, a 2011 book by Florida State University meteorologist Sharon E. Nicholson.

"When air masses are forced over mountains and downslope, they warm and their capacity for holding water vapor increases," wrote Susan Woodward, an emeritus geography professor at Virginia's Radford University, on a website about deserts. On the leeward side of a mountain, she added, evaporation happens faster than rainfall, creating an arid environment.

Kalahari Desert

360,000 square miles (930,000 square km)

The Kalahari Desert covers large tracts of South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. It averages less than 20 inches (500 mm) of rain a year in, but some locations receive less than 8 inches (200 mm) annually, according to the 1991 book The Kalahari Environment by David G. Thomas and Paul A. Shaw.

Described as "featureless" by the Encyclopedia Britannica, the Kalahari is mostly covered by sand sheets that were formed sometime between 2.6 million and 11,700 years ago, probably due to the action of wind and rain. The sheets have been virtually unchanged since then.

The Kalahari was also a site of human activity thousands of years ago. In one excavated area, South Africa's Wonderwerk Cave, archaeologists found evidence of fires lit about one million years ago. A separate discovery of artifacts in Botswana's Tsodilo Hills implied humans performed rituals 70,000 years ago.

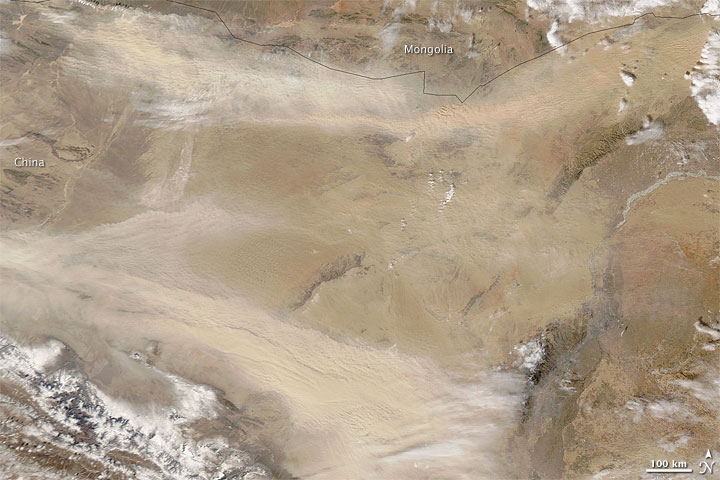

Gobi Desert

800,000 square miles (1.3 million square km)

Encompassing large regions of China and Mongolia, the Gobi Desert is arid in parts and more "monsoon-like" in others, meaning it sees wet and dry seasons, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Rainfall varies from about 2 to 8 inches a year (50 mm to 200 mm), depending on the location. The eastern region in particular gets a lot of rainfall in the summer, similar to how monsoons operate in wetter regions.

In 2011, strange zigzag patterns in the Gobi emerged in Google's pictures, prompting a range of conspiracy theories that even included aliens. But the lines were most likely used to calibrate Chinese spy satellites to help the spacecraft orient themselves in orbit, said Jonathon Hill, a research technician and mission planner at the Mars Space Flight Facility at Arizona State University.

The Gobi is also a good spot for dinosaur-hunting. A rare Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton uncovered in that region was auctioned off in 2012, fetching $1 million amid a legal dispute.

Arabian Desert

900,000 square miles (2.3 million square km)

The Arabian Desert encompasses Saudi Arabia and surrounding countries such as Oman and parts of Iraq. How dry and hot the desert is depends on where you're standing. The interior of the desert can get to a scorching, dry 129 F (54 C). Areas on the coast and in the highlands, however, have more humidity and can also have fog and dew during the cooler parts of the day, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

On average, annual rainfall is less than 4 inches (100 mm), but depending on the region it can range anywhere from 0 to 20 inches (0 to 500 mm). But human activity has artificially irrigated and greened parts of the desert.

Crop circles exploded in abundance in Saudi Arabia during the past three decades, according to a series of Landsat images. These are possible because engineers drilled into a "fossil" water acquifer that is more than 20,000 years old, according to NASA. It has been estimated that at current rates of usage, the water will go dry in 50 years.

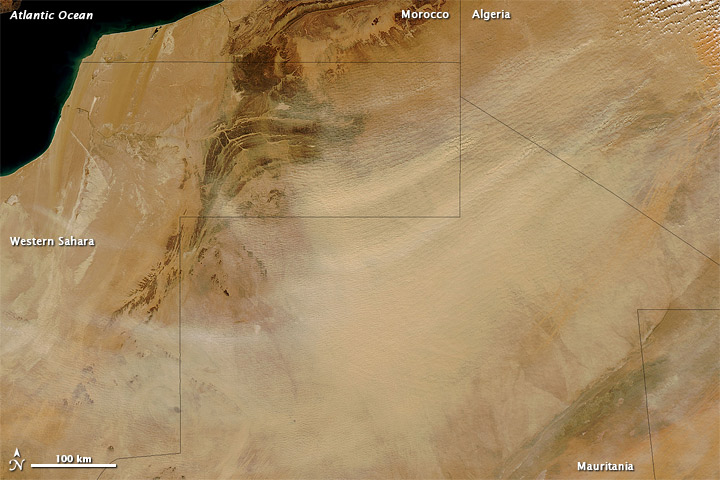

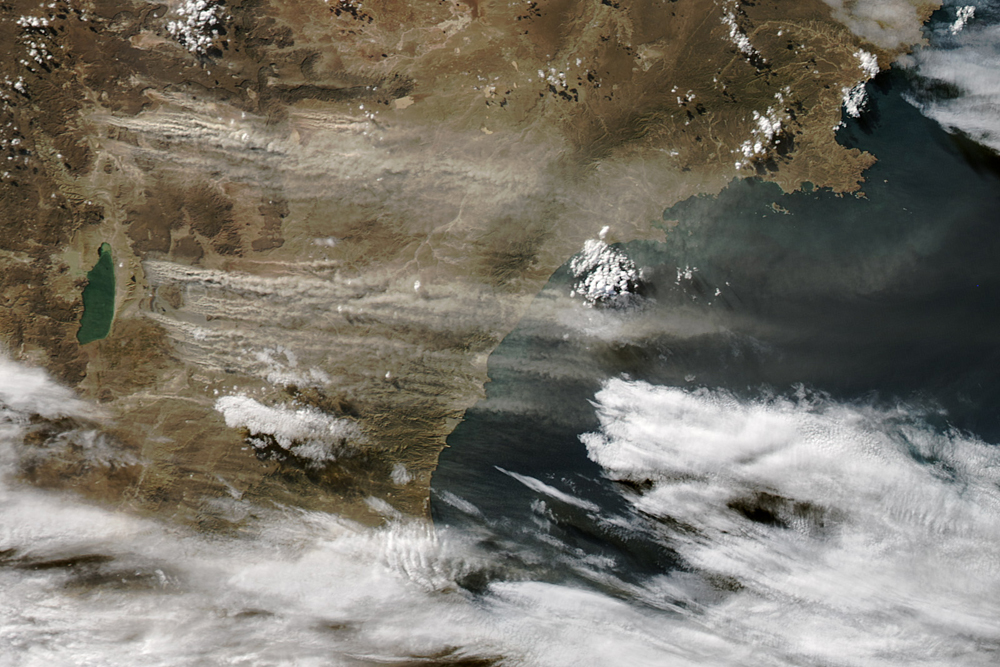

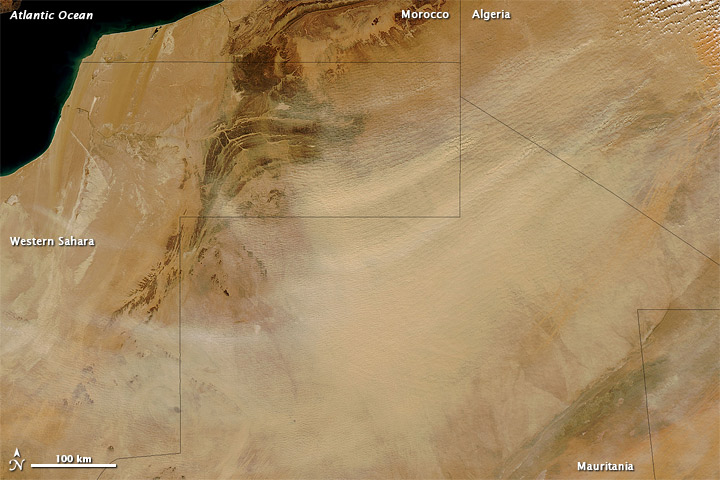

Sahara

3.3 million square miles (8.6 million square km)

The Sahara is notable not only for its vast size, but parching lack of rainfall. Annual precipitation in the world's second-largest desert is less than 0.9 inches (25 mm) every year. On the east side of the desert, according to NASA, rainfall could be as low as 0.2 inches (5 mm) annually.

While water doesn't often fall to the ground, it's common for water droplets to hover above the desert as fog. There isn't much vegetation in the Sahara to hold on to heat after the sun goes down, so the temperatures can actually get quite cold at night. The sudden shift between day and night temperatures can bring about the fog.

The desert also features a high volcano, Emi Koussi, which is in Chad at the southeastern end of the Tibesti Range. Standing 11,204 feet (3,415 meters) above sea level, there are lava flows and other volcanic features that appear to be as young as two million years old. There is also an active thermal region on the volcano's south flank.

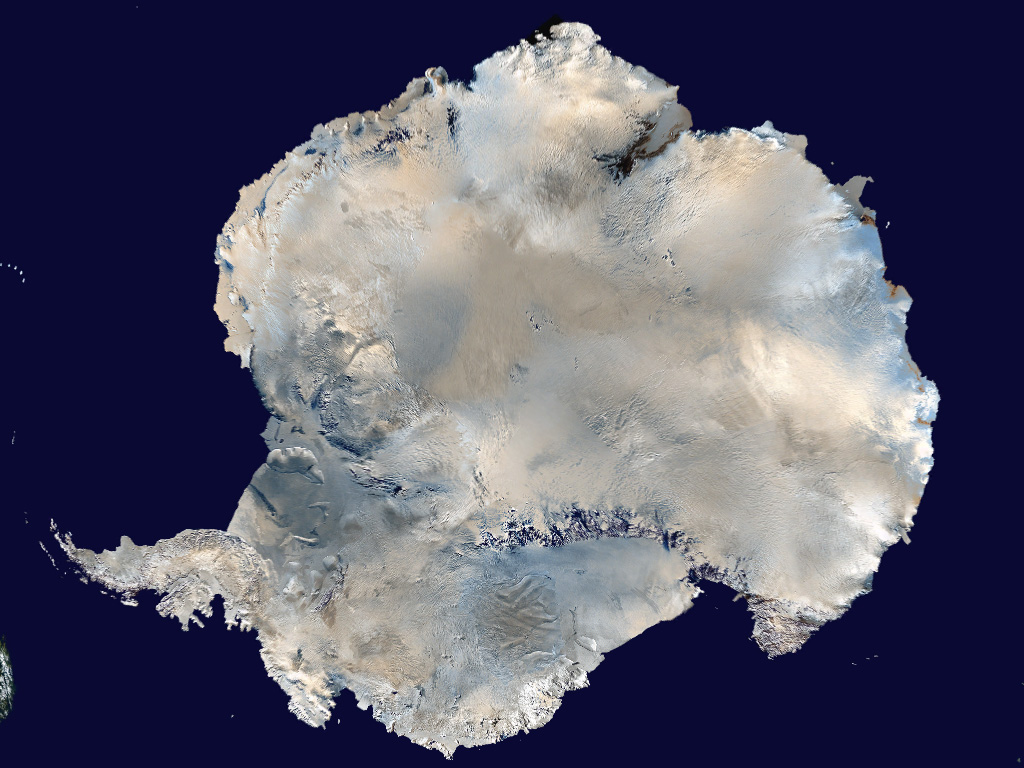

Antarctica

5.5 million square miles (14.2 million square km)

Nestled around the South Pole, where the coldest temperature on Earth was recorded and which doesn't receive sunlight for months every year, it's sometimes hard to think of icy Antarctica as a desert. But it is the world's largest one because very little precipitation falls there — on average, it gets less than 2 inches (50 millimeters) a year, mostly as snow.

Despite the low snowfall, vast glaciers cover 99 percent of Antarctica's surface. That's because the average temperature (minus 54 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 48 degrees Celsius) slows down evaporation to a crawl. Over long periods of time, the snowfall accumulates at a rate faster than Antarctica's ablation, according to "Discovering Antarctica," a project of the U.K.'s Royal Geographical Society.

Parts of Antarctica are showing strong signs of warming up along with global climate change, however. Temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula have increased by 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.5 degrees Celsius) over the past 50 years — five times the rate of the rest of the planet. And scientists think that warm ocean waters could be melting Antarctica's glaciers as they flow under the floating tongues of ice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.