Ancient Feathered Shield Discovered in Peru Temple

Hidden in a sealed part of an ancient Peruvian temple, archaeologists have discovered a feathered shield dating back around 1,300 years.

Made by the Moche people, the rare artifact was found face down on a sloped surface that had been turned into a bench or altar at the site of Pañamarca. Located near two ancient murals, one of which depicts a supernatural monster, the shield measures about 10 inches (25 centimeters) in diameter and has a base made of carefully woven basketry with a handle.

Its surface is covered with red-and-brown textiles along with about a dozen yellow feathers that were sewn on and appear to be from the body of a macaw. The shield would have served a ritualistic rather than a practical use, and the placement of the shield on the bench or altar appears to have been the last act carried out before this space was sealed and a new, larger, temple built on top of it. [See Photos of the Shield & Ancient Murals]

The discovery of this small shield, combined with the discovery of other small Moche shields and depictions of them in art, may also shed light on Moche combat. Their shields may have been used in ceremonial performances or ritualized battles similar to gladiatorial combat, Lisa Trever, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, told LiveScience.

Trever and her colleagues, Jorge Gamboa, Ricardo Toribio and Flannery Surette, describe the shield in the most recent edition of Ñawpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology.

Macaw feathers

Though only about a dozen feathers now remain on the shield, in ancient times it may have had a more feathered appearance. "I suspect that originally it had at least 100 feathers sewn on the surface" in two or more concentric circles, Trever said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Moche people, who lived on the desert coasts and irrigated valleys of the Pacific side of the Andes Mountains, likely had to import the feathers, as macaws resided on the eastern side of the Andes, closer to the Amazon.

What symbolic meaning the macaw had for the Moche is a mystery. "We know that the Moche used many animal metaphors in their art and visual culture," Trever said. "They may have had a specific symbolic meaning to the macaw, but because the Moche didn't leave us any written records we don't know precisely what they thought."

Ancient murals

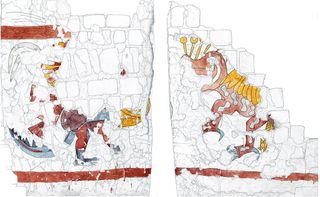

The shield was found close to two ancient murals, one of which depicts a "Strombus Monster," a supernatural beast with both snail and feline characteristics, and the other an iguanalike creature. The researchers note in their paper that the monster is often shown in Moche art battling a fanged humanlike character called "Wrinkle Face" by some scholars. The iguana in turn is often shown as an attendant accompanying Wrinkle Face on his journeys. [Top 10 Beasts & Dragons: How Reality Made Myth]

Although a depiction of Wrinkle Face has yet to be found in the sealed area where the shield is located he may yet turn up in future excavations. "What the exact relationship is between the deposition of the shield and the adjacent pictorial narrative is an active question," Trever said.

Moche gladiatorial combat?

It appears as if the Moche liked to keep their shields small, bringing up the question of whether they were meant for something like gladiatorial combat or some other type of fighting.

Whereas the newly discovered shield was meant for ritual and not for combat, the researchers note that another small Moche shield, this one found at the site of Huaca de la Luna, was likely meant for combat, being made of woven cane and leather, but measuring only 17 inches (43 cm) in diameter. In addition, depictions of Moche shields in ceramic art show people wearing small circular or square shields on their forearm.

It's "more like a small shield that's used to protect the forearm and maybe held over the face in hand-to-hand combat with clubs," she said of the Moche shields. "They apparently didn't need, or didn't use, large shields to protect themselves from volleys of arrows or spears that were thrown."

We "have to think about the style of hand-to-hand combat" they were used for, she added. "Is it something that is more ritual in nature, more of a ritual combat, gladiatorial combat," Trever said.

Jeffrey Quilter, director of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, has proposed another idea as to why Moche shields were so small. He points out that the Moche used a two-handed club that gave them great reach and could land a lethal blow.

"The power of such weapons may have been so great as to render shields effectively useless, perhaps resulting in their diminished size over time, becoming more useful as arm guards or to ward off the occasional sling stone or dart than as true shields for body protection," he writes in a paper published in the book "The Art and Archaeology of the Moche" (University of Texas Press, 2008). He notes that the Moche do appear to have used some long-range weapons in combat such as sling stones and darts.

Regardless of why the Moche preferred small shields, their repeated depiction indicates the shields served their purpose well. They "did seem to use very small shields compared to what we know of from other parts of the world, but they seemed to have served for the style of battle that they performed," Trever said.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Most Popular