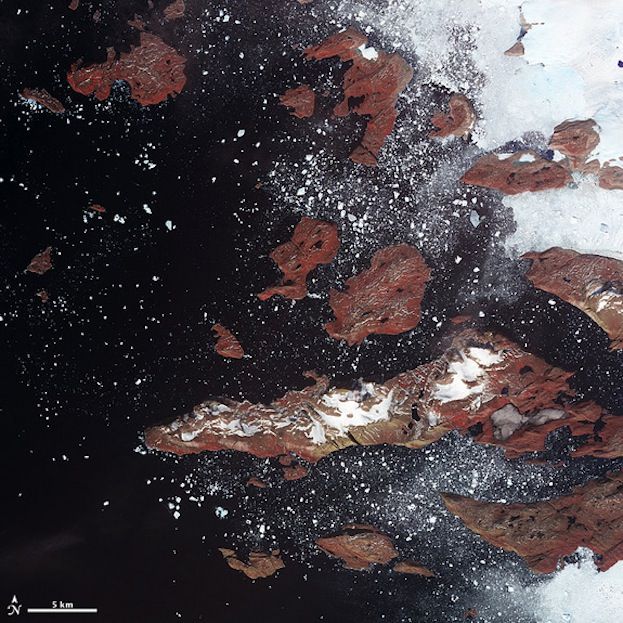

Greenland Icebergs May Have Triggered 'Big Freeze'

In a warming world, what could cause temperatures to suddenly plummet across the Northern Hemisphere? Scientists have tried to answer this question for decades, ever since they discovered geological and biological evidence for the "Big Freeze."

Now, a new study points to an armada of icebergs or meltwater from Greenland as a possible cause for the sudden climate change called the Younger Dryas, or the Big Freeze. The findings were published online July 10 in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Starting roughly 12,900 years ago, the Big Freeze halted the Northern Hemisphere's transition from an Ice Age to today's relatively warm, interglacial period. In just a decade, glacial cold returned to the northern latitudes. The tropics shifted more slowly, with changes in monsoon intensity and the amount of rainfall they received. Only Antarctica went untouched.

Big Freeze

In the most widely accepted model, researchers have suggested massive glacial floods from North America shut down warm ocean currents in the North Atlantic, leading to the climate cooling. Just before the Younger Dryas, the continent's Laurentide Ice Sheet was melting, and freshwater floods could have poured into the Atlantic or Arctic oceans through the St. Lawrence or Mackenzie rivers, respectively. However, there is ongoing debate about the size and timing of the floods.

Greenland's ice sheet was also presumably melting 13,000 years ago, but it has rarely been named as a prime suspect in the Younger Dryas cooling. Widespread geological clues for a big Greenland ice breakup hadn't been found. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

But in seafloor sediments in the Labrador Sea, near Greenland's southern tip, scientists from the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland think they've found their smoking gun. There, a ship pulled up cores of mud with rock fragments carried by icebergs from Greenland and dropped into the ocean as the ice melted. Some of the rubble is distinctly older, by about 1 billion years, than rock rafted into the Labrador Sea by North American icebergs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Predicting future from the past

Combined with other geochemical evidence from the mud cores (cylinders of sediment drilled out of the seafloor), the findings suggest a sudden pulse of Greenland meltwater hit the Labrador Sea about 13,000 years ago, just before the Younger Dryas cooling started.

"It wasn't as giant as the Laurentide Ice Sheet, but these more minor ice sheets can also contribute to ocean-climate interactions," said Paul Knutz, lead study author and a marine geologist at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. Through either a crack-up that released an iceberg flotilla, or a freshwater flood, the Greenland Ice Sheet lowered salinity in the Labrador Sea so much that it affected heat transport in the North Atlantic, according to oceanographic models.

Though the study still can't rule out the Laurentide Ice Sheet as the cause of the Younger Dryas cooling, the evidence points to Greenland as "a very likely culprit," Knutz told LiveScience.

Evidence stacking up

Although the link between the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet and climate change during the Younger Dryas is still not conclusively established, the evidence seems to be stacking up in favor of a connection, said Eelco Rohling, a paleoclimatologist at the Australian National University in Canberra who wasn't involved in the study. "The timing relationship seems OK, but coincidence does not imply causality," he told LiveScience.

Understanding how Greenland melting changed ocean circulation and climate in the past can help predict the ice sheet's future role in climate change, the researchers said. "This does have implications for the future," Knutz said.

Another big melt from Greenland's shrinking ice sheet could shift the North Atlantic's circulation.

"If it turns out that the Greenland Ice Sheet was a major player — not just in this last climate flick, the Younger Dryas, but in the rapid, millennial-scale climate swings through the last glacial period — then I think we need to be more concerned about potential meltwater fluxes from this region," Knutz said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.