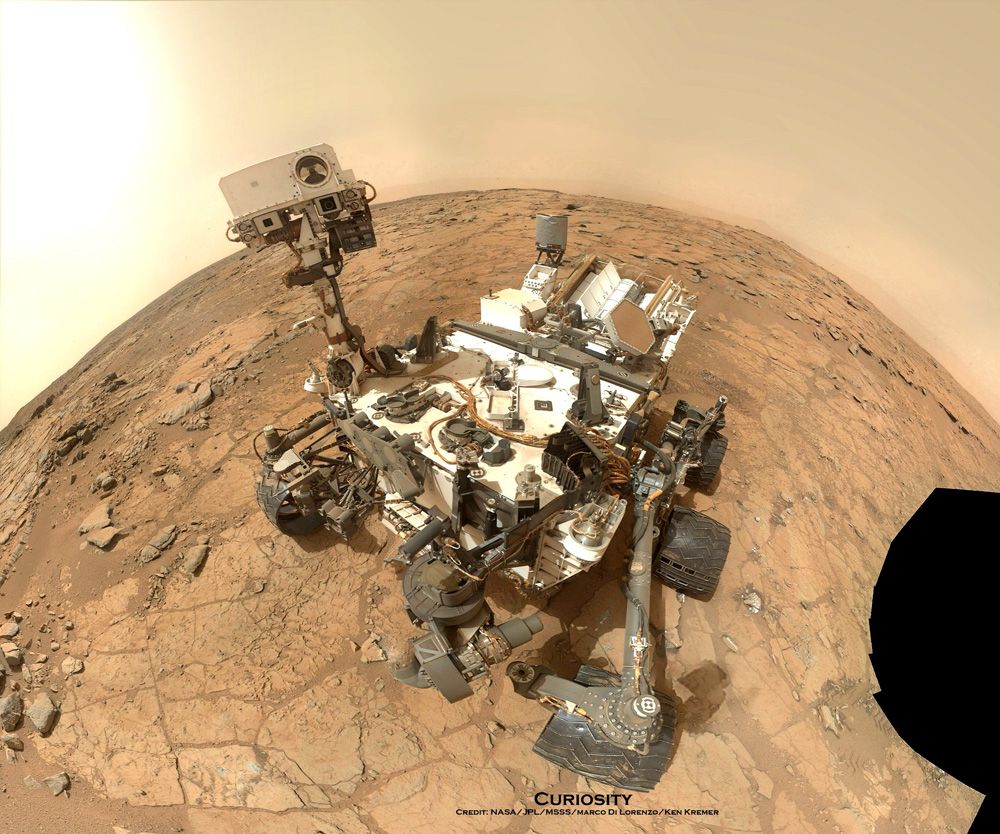

One year ago today (Aug. 5), NASA's Curiosity rover survived its harrowing and unprecedented Red Planet landing, setting off celebrations around the country.

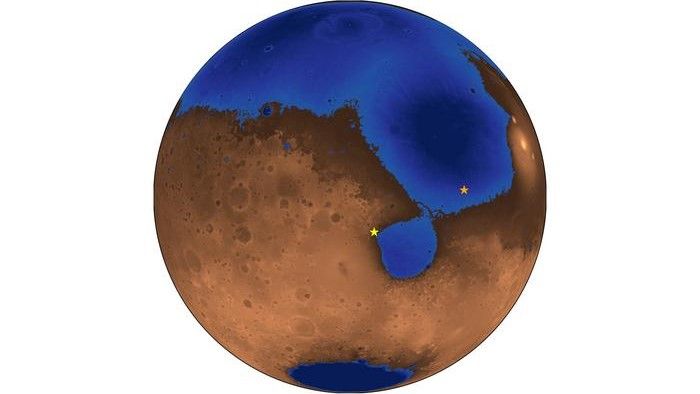

The 1-ton robot has achieved a great deal in its 12 months on Mars, discovering an ancient streambed and gathering enough evidence for mission scientists to declare that the planet could have supported microbial life billions of years ago.

And more big finds could be in the offing, as Curiosity is now trekking toward its ultimate science destination: the foothills of a huge and mysterious mountain that preserves, in its many layers, a history of Mars' changing environmental conditions. [Curiosity's First Year on Mars in Two Minutes (Video)]

"The time has gone by quickly, but we're amazed at how much we were able to accomplish," said Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, a geologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. "The whole thing has just been the experience of a lifetime."

Seven minutes of terror

Curiosity was too big to land cushioned inside giant airbags, as its smaller cousins Spirit and Opportunity did back in 2004, so mission engineers devised an entirely new touchdown system for the car-size rover — one that had seemingly been pulled from the pages of a sci-fi novel.

On the night of Aug. 5, 2012 U.S. Pacific time (early morning Aug. 6 EDT and GMT), a rocket-powered sky crane lowered Curiosity to the Martian surface on cables, then flew off and crash-landed intentionally a safe distance away.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Curiosity rover team erupted in cheers at mission control at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena when it became clear that the six-wheeled robot had survived its "seven minutes of terror" plunge through the Martian atmosphere. The celebration was echoed in New York City's Times Square and many other places, where people had gathered to watch the action live.

"We're on Mars again," NASA chief Charles Bolden said just minutes after Curiosity touched down inside the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater, kicking off a planned two-year surface mission to determine if the Red Planet has ever been capable of supporting microbial life. "It doesn't get any better than this," he said. [Video: Curiosity's '7 Minutes of Terror' Landing]

Grotzinger said the memories and emotions of landing night remain vivid 12 months later.

"Looking back on it, I just cannot believe it's been a year," he told SPACE.com.

Mission accomplished

Curiosity stuck close to its landing site for most of its first 12 months on the Red Planet. Observations from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter suggested that rocks in the area may have been exposed to liquid water long ago, and mission scientists wanted the rover to check out these landforms.

The strategy quickly paid off. In September, less than two months after touchdown, the mission team announced that Curiosity had rolled through an ancient streambed, where water had flowed perhaps hip-deep in places.

A nearby site dubbed Yellowknife Bay turned out to be even more exciting. There, in early February, Curiosity drilled 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) into a Red Planet rock and collected samples — the first time a rover had ever performed this complicated maneuver on another world, NASA officials said.

Analysis of these samples allowed scientists to check off their main mission goal just seven months into Curiosity's stay on Mars. In March, the mission team announced that Yellowknife Bay was indeed habitable billions of years ago.

"We have found a habitable environment that is so benign and supportive of life that probably — if this water was around and you had been on the planet, you would have been able to drink it," Grotzinger said at the time.

On to Mount Sharp

But Curiosity isn't resting on its laurels. Last month, the rover began the long trek to Mount Sharp, which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 km) into the Red Planet sky from Gale Crater's center.

Mission scientists have been targeting Mount Sharp's foothills since before Curiosity launched in November 2011. The mountain's lower reaches show signs of long-ago exposure to liquid water, while upper levels look like they've always been high and dry.

The Curiosity team wants the rover to climb partway up the gently sloping mountain, ideally crossing a threshold about 2,625 feet (800 meters) up that seems to separate a much wetter early Mars from the arid planet we know today.

"We hope that we'll be able to drive long enough and high enough to be able to cross that boundary — that'll be a really key one for us," Grotzinger said. "I think that this many-hundred-meter climb through the foothills of Mount Sharp could be just a great story in understanding the early environmental evolution of Mars."

The drive from the Yellowknife Bay area to Mount Sharp's base will cover about 5 miles (8 km) of straight-line distance and will probably take a year or so, rover team members say.

"We hope to arrive at the base of Mount Sharp and get stuck into that part of the mission probably near the end of our nominal mission of two years," Grotzinger said. "It's going to take a while to get there." (NASA officials have said they'll continue to operate Curiosity as long as the rover is scientifically viable.)

Curiosity's leisurely pace — its top driving speed over hard, flat ground is 0.09 mph (0.14 km/h) — isn't the only reason the drive will take so long. The team also plans to stop at various places along the way to do some science work.

For example, mission scientists want to know what the relationship is between the water-exposed rocks of Yellowknife Bay and Mount Sharp. Are they part of the same unit, or do they differ in age?

"As we drive along, we want to stop and make measurements of those rocks to try to figure out how to link Yellowknife Bay with the base of Mount Sharp," Grotzinger said. "That'll be important someday."

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Curiosity's success has already had a big impact on NASA's Mars program and the future of Red Planet exploration more broadly.

For instance, the space agency announced in December that it will launch another unmanned rover toward the Red Planet in 2020 — one whose chassis and landing system will be based heavily on Curiosity's hardware. The sky crane can also be used to land heavy equipment needed for an eventual human mission to the Red Planet, NASA officials have said.

Grotzinger said he and the rest of the rover team are proud of all that Curiosity has accomplished thus far, but he stressed that they can't take all the credit for the mission's success.

"It just underscores the importance and the value of NASA's Mars program," Grotzinger said. "If we looked farther, as trite as it sounds, it's because we stood on the shoulders of giants. The rover missions that came before us and the orbiter missions, and that synergy between the surface missions and the orbiter missions — it just demonstrates how well that works."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.