Pink Alien Planet Is Smallest Photographed Around Sun-Like Star

Astronomers have snapped a photo of a pink alien world that's the smallest yet exoplanet found around a star like our sun.

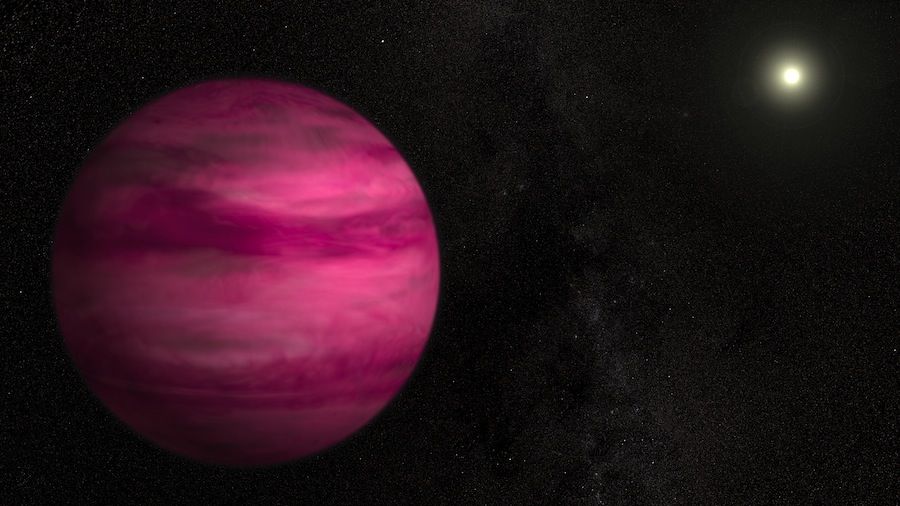

The alien planet GJ 504b is a colder and bluer world than astronomers had anticipated and it likely has a dark magenta hue, infrared data from the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii revealed.

"If we could travel to this giant planet, we would see a world still glowing from the heat of its formation with a color reminiscent of a dark cherry blossom, a dull magenta," study researcher Michael McElwain, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement from the space agency. [See Photos of the Pink Alien Planet GJ 504b]

"Our near-infrared camera reveals that its color is much more blue than other imaged planets, which may indicate that its atmosphere has fewer clouds," McElwain added.

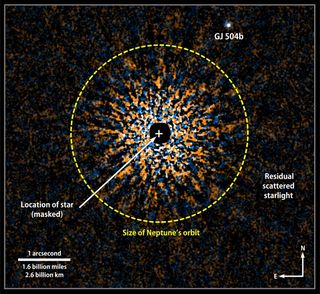

The exoplanet orbits the bright star GJ 504, which is 57 light-years from Earth, slightly hotter than the sun and faintly visible to the naked eye in the constellation Virgo. The star system is relatively young at roughly 160 million years old. (For comparison, Earth's system is 4.5 billion years old).

Though it is the smallest alien world caught on camera around a sun-like star, the gas planet around GJ 504 is still huge — about four times the size of Jupiter. It lies nearly 44 Earth-sun distances from its central star, far beyond the system's habitable zone, and it has an effective temperature of about 460 degrees Fahrenheit (237 Celsius), according to the researchers' estimates.

The exoplanet's features challenge the core-accretion model of planet formation, they study's researchers say. Under this widely accepted theory, asteroid and comet collisions produce a core for Jupiter-like planets and when they gets massive enough, their gravitational pull draws in gas from the gas-rich disk of debris that circles their young star. But this model doesn't explain the formation of planets like GJ 504b that are far away from their parent star.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is among the hardest planets to explain in a traditional planet-formation framework," study researcher Markus Janson, a Hubble postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University in New Jersey, said in a statement. "Its discovery implies that we need to seriously consider alternative formation theories, or perhaps to reassess some of the basic assumptions in the core-accretion theory."

The discovery of GJ 504b was part of a larger survey, the Strategic Exploration of Exoplanets and Disks with Subaru or SEEDS program, which seeks to explain how planetary systems come together by looking at star systems of many sizes and ages with images at near-infrared wavelengths.

Direct imaging can help scientists measure an alien planet's luminosity, temperature, atmosphere and orbit, but it's difficult to detect faint planets next to their bright parent stars. The study's leader, Masayuki Kuzuhara of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, said the task is "like trying to take a picture of a firefly near a searchlight."

Two of the Subaru Telescope's tools in particular — the High Contrast Instrument for the Subaru Next Generation Adaptive Optics and the InfraRed Camera and Spectrograph — help scientists tease out light from these faint exoplanet sources.

The study on GJ 504b will be published in The Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.