Controversial 'HeLa' Cells: Use Restricted Under New Plan

For decades, the immortal line of cells known as HeLa cells has been a crucial tool for researchers. But the cells' use has also been the source of anxiety, confusion and frustration for the family of the woman, Henrietta Lacks, from whom the cells were taken without consent more than 60 years ago.

Now, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has brokered a compromise between the desire of the Lacks family for privacy and the interests of research, at least with regard to genomic sequence information taken from the cells, officials announced today (Aug. 7).

"In 20 years at NIH, I can't recall a specific circumstance more charged with scientific, societal and ethical challenges than this one," said Francis Collins, NIH director, at a news conference earlier today.

According to the agreement reached with the family, researchers will need to apply for access to data on the HeLa genome sequence, and receive approval from a panel that includes members of the Lacks family, according to NIH Director Francis Collins and deputy director Kathy Hudson, who outlined the plan that appears tomorrow (Aug. 8) in the journal Nature. (The cells are code-named HeLa after the first two letters of Henrietta Lacks' name.)

"For more than 60 years our family has been pulled into science without our consent and researchers have never stopped to talk with us to share information with us or give us a voice in the conversation about the HeLa cells until now,"Jeri Lacks-Whye, Lacks' granddaughter, said during the news conference.

Lacks-Whye described the publication of the first HeLa genome paper under this new policy as a "historic, game-changing event." This paper is also published in Thursday's issue of Nature.

The Lacks family has not received any financial compensation for the use of the cells, and the agreement will not change that. [The 9 Most Bizarre Medical Conditions]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The agreement represents a reasonable balance between the family’s privacy interests and the open sharing that allows research to advance, said Rebecca Dresser, a fellow at The Hastings Center and a professor of ethics in medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in brokering the agreement.

"The most interesting praiseworthy element, in my view, is that the family will be participating in the group that decides whether to grant access to the sequence data. This will give them the control that many other members of the public say they want over how their samples are used," Dresser told LiveScience. "It is also good that they will be involved, after so many years of being neglected."

Without consent, again

Four months of discussions among the family, NIH officials and others began after a group at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in March posted sequence data from a HeLa cell line in publicly accessible databases. Rebecca Skloot, author of the book "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" (Broadway Books, 2011), detailed the family's frustration in an article in The New York Times.

"'That is private family information,'" Skloot quoted Jeri Lacks-Whye, Lacks' granddaughter, as saying. "'It shouldn't have been published without our consent.'"

Genetic information can be stigmatizing, Skloot wrote, and while employers and health insurance providers cannot use it to discriminate, no such legal protections exist for life insurance, disability coverage or long-term care.

The publication of the genomic data without the family's consent called to mind the origin of the cell line itself.

In 1951, a doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital took a specimen for culture from a cervical tumor that belonged to Henrietta Lacks, a then 31-year-old African-American woman, without informing her that he was doing so, or asking her consent, as is now required.

Good for science, not for the family

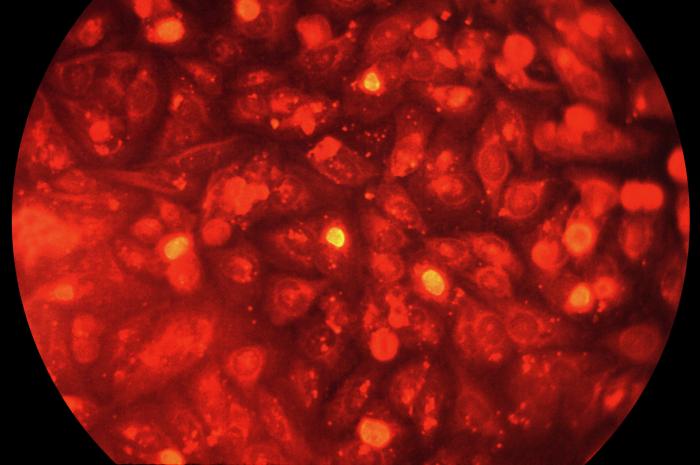

Cells from that biopsy became the first to successfully replicate continuously in culture (and hence be called immortal), and have since played a crucial role in many scientific breakthroughs. Researchers sent them into space to study the effects of zero gravity, and used them to develop the polio vaccine, for example. The cells are named in more than 70,000 research papers.

Lacks' cancer killed her not long after the biopsy, but the problems didn't end. Her family remained unaware of her immortal cells until 20 years later, when scientists began using her children in research without their knowledge, Skloot reported. Later, their medical records were released and published without consent.

In Nature, Collins and Hudson pointed out that the genome of HeLa cells is not identical to Lacks' original genome. The cells carry the changes that made them cancerous, and have undergone further changes over the time they have spent in cell cultures.

Even so, they said, the sequences carry information with implications for her descendants.

The new NIH plan does not have the weight of law; although the organization funds most medical research in the U.S., researchers funded by other entities remain free to sequence HeLa cells and post the information anywhere.

"However, we urge the research community to act responsibly and honor the family's wishes," Collins and Hudson said.

A growing concern

Although the Lacks family's situation is exceptional, privacy is a major concern for genomics. As a rule, science benefits from the easy exchange of information, and results of sequencing projects are often posted in open-access databases.

While donors' identities are not included, Web sleuthing can sometimes find them, as one researcher reported in the Jan. 18 issue of the journal Science.

Under current U.S. research rules, samples taken in the course of a person's medical care may be used in research without the person's awareness or explicit consent if the information is recorded without identifying information.

"The problem is that absolute anonymity cannot be guaranteed in light of current knowledge and technology. Officials are considering whether to propose a change in the current rule," Dresser said. "In surveys, focus groups, and interviews, many would-be research contributors say they want the power to consent to research uses of their samples."

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com .