Can Elon Musk's Superfast 'Hyperloop' Transit System Really Be Built?

Updated on Tuesday, Aug. 13, at 7:38 a.m. ET.

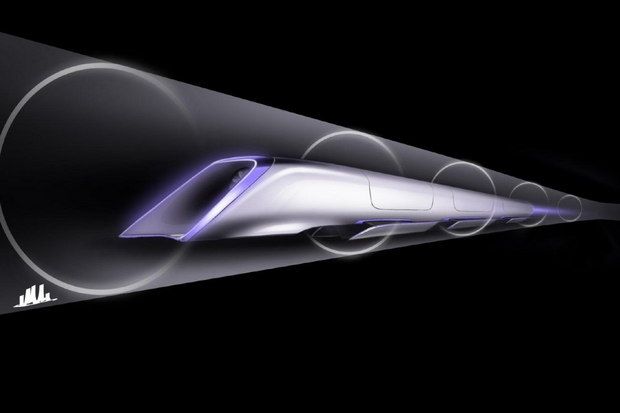

Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk unveiled new details today (Aug. 12) about his proposed "Hyperloop" project, a futuristic, super-fast transportation system that could ferry passengers between Los Angeles and San Francisco in about 30 minutes.

The high-speed Hyperloop, which Musk has described as a "cross between a Concorde, a rail gun and an air hockey table," could travel at a blistering pace of 760 mph or so (1,220 km/h).

Moving people at such high speeds could ease congestion problems along intercity highways and could provide more efficient, affordable and "greener" alternatives to bus, train or air travel, Musk said. [Video: What on Earth Is a Hyperloop?]

But while ultra high-speed transportation has myriad benefits, developing these systems also comes with significant technical and political challenges, said James Powell, an American physicist and co-inventor of the superconducting Maglev transportation system, high-speed trains that are propelled by powerful magnets.

For one, traveling at such high speeds will require the Hyperloop to move along a track that avoids turns and hills.

"It's doable, but you have to build a track or tunnel that's very straight," Powell told LiveScience. "At that speed, the track has to be straight and flat, to avoid bumpiness. When you're going 600 miles per hour, you can't really go around curves, and you'd have to be very flat, because without causing excessive G-forces, you probably wouldn't be able to adjust to changing elevations rapidly."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

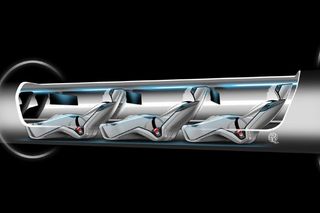

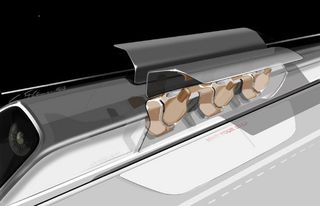

The Hyperloop project is designed to accelerate 6.5-feet-wide (2 meters) pods through a low-pressure tube. The Hyperloop pods would ride on a cushion of air, rather than on traditional rails, which would enable them to reach superfast speeds.

Superconducting Maglev (short for magnetic levitation) vehicles, which Powell developed together with Gordon Danby, use magnets to create lift and thrust, and can travel fast because they do not have to contend with friction from wheels and axles on a rail. Maglev trains are designed to travel at around 300 mph (483 km/h), but in December 2003, a Japanese Maglev train clocked a top speed of 361 mph (581 km/h). Musk's concept of the Hyperloop would transport passengers at double the speed of Maglev trains.

Musk said the Hyperloop is a more efficient and cost-effective alternative to the California High-Speed Rail project, a nearly $70 billion system planned to link most of the major cities in California, including Sacramento, San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego.

"When the California 'high speed' rail was approved, I was quite disappointed, as I know many others were too," Musk wrote in a blog post today about the Hyperloop project. "How could it be that the home of Silicon Valley and [the Jet Propulsion Laboratory] — doing incredible things like indexing all the world's knowledge and putting rovers on Mars — would build a bullet train that is both one of the most expensive per mile and one of the slowest in the world?"

Musk said any major investments in transportation should have equally major returns, and should be pursued only if they do, in fact, present a better alterative to flying or driving.

Yet, the move toward newer transportation systems — be it high-speed rail or concepts such as the Hyperloop — are part of a fast-growing trend in transportation innovation, said Powell.

"The move toward higher speed, better service, cheaper travel, and something less environmentally polluting, is going to happen — it's the wave of the future," Powell explained. "Whether [the Hyperloop] system proceeds or not will probably depend on how many people will benefit from building a high-speed system between Los Angeles and San Francisco." [How Elon Musk's Hyperloop Transit System Works (Infographic)]

That decision will likely be colored by a combination of economics and politics, Powell added.

"It will happen inevitably, but it's not really technology controlling that," he said. "It's the political will that will control whether it happens."

The more public transportation systems rely on government subsidies, the likelier these projects are to stall, Powell said. In Japan, where there are plans to extend existing Maglev train service eventually to carry passengers between Tokyo and Osaka — two cities located about 310 miles (500 km) apart — in one hour, officials are grappling with whether passenger-only trains can generate enough revenue to recoup the cost to build and maintain the project.

"It's a problem that all high-speed, passenger-only systems face," Powell said. "Where do you get the money? And can it be funded by private investment?"

Musk labeled the Hyperloop project as "low priority," maintaining that he will continue to devote most of his attention to his other more high-profile projects: the Tesla electric-car and SpaceX rocket companies. Still he stated he intends to be a key investor in the project. And while Musk would like the Hyperloop to be an open-source endeavor, he also stated he is willing to develop a small-scale prototype to demonstrate the validity of the concept.

"I'm not trying to make a ton of money on this, but I would like to see it come to fruition," Musk told reporters in a news briefing today. "I think it might help if I did a demonstration article, so I think I probably will do that, actually."

Since the Hyperloop is not a top priority, Musk said a prototype may take three to four years to build. More information about the Hyperloop project can be found on Musk's blog.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct the speed of Hyperloop, which is about 760 mph, and to correctly describe Hyperloop as being aboveground not underground.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.