'Cannibal' Monster Galaxies Lose Appetite In Old Age

At the core of most galaxy clusters in our universe, there are cosmic cannibals — monster galaxies that gobble up their neighbors to grow bigger and bigger in size. But the appetite of these hungry objects seems to fade as they get older, a new study reveals.

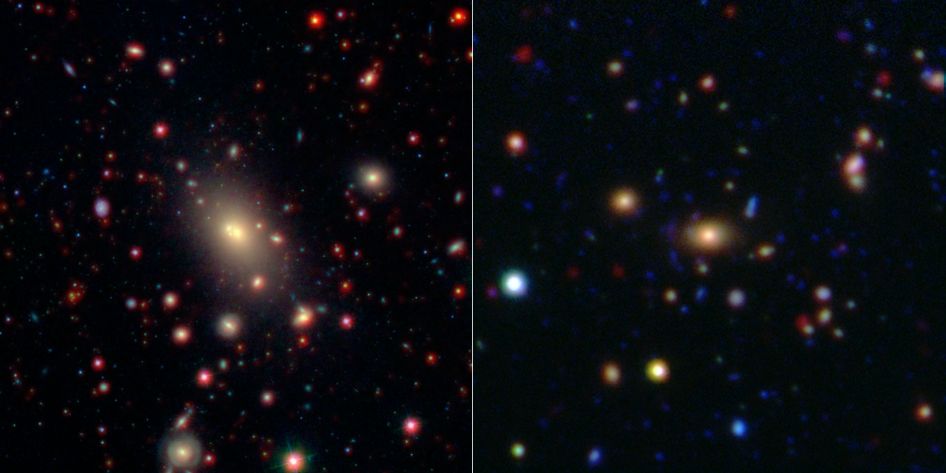

The discovery comes from a review of observations data collected by two of NASA's infrared space observatories, the Spitzer Space Telescope and Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), researchers said.

"We’ve found that these massive galaxies may have started a diet in the last 5 billion years, and therefore have not gained much weight lately," study author Yen-Ting Lin of the Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan, said in a statement. [When Galaxies Collide: Photos of Cosmic Crashes]

Galaxy clusters are arranged around the brightest member of their bunch, formally called the brightest cluster galaxy, or BCG. Over time, these central galaxies fatten up by cannibalizing the other galaxies around them and taking on other stars.

Since astronomers don't have billions of years to watch how these monsters evolve, they sampled a wide range of nearly 300 galaxy clusters, the oldest dating back to a time when the universe was 4.3 billion years old, and the youngest dating back to the universe's 13 billionth birthday. (The current age of our universe is estimated at 13.8 billion years).

"You can't watch a galaxy grow, so we took a population census," Lin explained in a statement from NASA. "Our new approach allows us to connect the average properties of clusters we observe in the relatively recent past with ones we observe further back in the history of the universe."

Lin and colleagues found that BCGs initially grew as predicted, but when the universe was about 8 billion years old these galaxies largely gave up their cannibal ways.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers are still looking for an explanation as to why BCGs seem to have changed their diet around 5 billion years ago. They note that it is possible that the galaxies are still growing in old age but the WISE and Spitzer surveys are not detecting a large numbers of stars in the more mature clusters.

"BCGs are a bit like blue whales — both are gigantic and very rare in number," Lin said. "Our census of the population of BCGs is in a way similar to measuring how the whales gain their weight as they age. In our case, the whales aren't gaining as much weight as we thought. Our theories aren't matching what we observed, leading us to new questions."

The Spitzer Space Telescope is an infrared observatory that launched on Aug. 25, 2003 and has spent nearly 10 years in space. NASA's WISE space telescope was an infrared all-sky survey tool that launched in 2009 ended its mission in 2011.

The findings have been detailed in the Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.