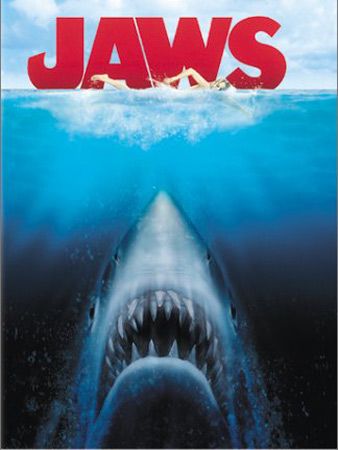

The Truth About Great White Sharks, 30 Years After 'Jaws'

Da-dum ... Da-dum ... Da-dum, da-dum da-dum da-dum!

Thirty years after the release of the movie "Jaws" those two notes, repeated ominously, still scare the Bermuda shorts off some people. But real great white sharks, unlike the glutton that starred in the film, are more than just the swimming set of teeth that dominates their popular image.

Especially to scientists, whose understanding of the beasts has grown since the movie came out.

"The image has changed a lot since 'Jaws,'" says shark expert Peter Klimley of the University of California at Davis. "Now when a shark is spotted, everybody throws on their free-diving gear to go see them."

Well, maybe not everybody, but certainly more than back in 1975.

"Jaws" did irreparable damage to the great white shark's reputation, and every time there's another shark attack, some people's minds jump to that old stereotype.

Yet t here are many other animals that are deadlier to humans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Marine biologists and educators have urged people to shed the perception of the great white shark as a vengeful, man-eating machine in favor of an intelligent, misunderstood, ancient sea creature.

Facts vs. reality

About six people are killed by sharks every year. Some 50,000 people die of snake bites. Elephants kill 500 people a year.

So why are great whites so feared?

At around 20 feet in length, great whites are the largest predatory fish. They're actually grey on top with a white underbelly.

This coloring pattern helps them hunt because it makes them difficult to spot from above and below -- the white belly blends in with the sky and the dark back blends in with the rocks below.

The distinctive coloring also distorts shark attack data and fuels the great white myth.

"They're the most often documented shark attacks, but not necessarily the most common," says George Burgess, curator of the International Shark Attack File. "Great whites are easily identifiable and any attack by one is sure to be documented. Attacks by other sharks are often not recorded because the species was not identified."

The oversized creature in the movie stuck to a steady diet of beachgoers, but in real life, sharks don't eat people.

"This whole idea that they are a man-eater is very wrong," Klimley told LiveScience. "They spit out humans. Humans aren't nutritious enough to be worth the effort."

True, some people get bitten, but it is rare that anyone is consumed by a great white.

Powerbars for sharks

Sharks love fat. Fat produces twice the energy of muscle, so it's the most efficient food for sharks.

Great whites prefer baby seals, which can have up to 50 percent fat content. They stalk seal colonies waiting for these treats.

Klimley tagged five sharks and observed their seal hunting and feeding habits over the course of a couple of months.

"Essentially, they get this prey, get it in their jaws, and carry it until it stops struggling," Klimley said. "They let the blood drain, the seal floats to the surface, and the sharks go up and take turns feeding on it."

Seals are like Powerbars for sharks -- one morsel provides enough energy to sustain a shark for up to six weeks, Klimley said.

Seals are tough to catch. They can change direction quickly, jump out of the water, and swim at more than 25 mph. At shark dinner parties, there is quite a bit of competition over who gets a bite. Sharks decide the feeding order in a surprising way.

When one manages to catch and kill a seal, the other sharks smell the blood in the water and show up for the meal once the kill bobs to the surface.

"They have a very ritualized display on who gets the next bite," Klimley said. "The one that splashes the most water gets the next bite. People think sharks are dumb, but they're communicating."

Despite this family-style dining, sharks do not actually hunt together.

"We suspect that they move from location to location as a group, but when they're at the seal colony they're searching and hunting independently," Klimley said.

A day in the life

"Thirty years ago when 'Jaws' was being made, everything we knew about white sharks was based on periodic observations close to the surface," says Randy Kochevar of Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Since then, Kochevar has used electronic tags to follow great whites through the Pacific Ocean. The sharks swim up and down the California coast and as far away as Hawaii, depending on the season.

Researchers at the SharkLab at California State University, Long Beach have been studying sharks since 1969. They also track great whites with electronic tags, and their findings support Kochevar's.

"The adults are seen at offshore islands. We only see the young ones along the shore," SharkLab director Chris Lowe said. "We see lots of bottom fish in the stomachs of young sharks, so this suggests that they are eating near shore. Once they grow a little bigger, they eat bigger fish, like mackerel, tuna, and bonito. Then they hit 10 feet and head to the Farallon Islands to eat [seals]."

On the West Coast, shark researchers have found that great whites range from northern California -- during elephant seal mating season -- down to Southern California and Mexico, where most of the juvenile sharks hang out.

This type of information helps conservation efforts, not only in California but in other places where great whites are common, like Australia and South Africa, Lowe said. People used to fish along shore with gill nets and sharks were often caught. The technique is now illegal.

Catching sharks

Commercial fishermen still catch sharks accidentally, which as backwards as it sounds, is actually good news for scientists.

"We work with commercial fleets, and they know if they catch one, they should bring it in immediately," Kochevar said. "We've never been successful trying to get them on our own."

This is precisely how Monterey Bay Aquarium ended up with a young great white that it was able to keep in captivity for 198 days. This shattered the previous record of 16 days, set in 1968, for keeping a shark in closed quarters.

Times have changed, as evinced by what happened to the previous record holder.

"The reason that that shark ended after 16 days was that the shark displayed aggressive behavior toward tank divers. Her time ended with a public execution," Kochevar said.

Not "in our wildest dreams" could researchers have imagined killing the current record holder. It was released back into the sea.

"I think our view of these animals has really changed," Kochevar said. "Now we see them as the magnificent, graceful, important animals that they are rather than as the mindless predators or deadly eating machines as they've been portrayed."

The Monterey Bay Aquarium shark was incredibly popular with aquarium visitors and scientists alike.

"That baby shark was a tremendous ambassador for sharks worldwide," Lowe said.

"Everybody was scared senseless by that movie. It's very difficult to clear the memory and reset the mind," Klimley said. "That's why it's very important to me that places like the Monterey Bay Aquarium have white sharks on display. People can see white sharks behaving naturally and not in some contrived, artificial situation."

Related Stories

- The Top 10 Deadliest Animals

- The Science of Shark Attacks and How to Avoid Them

- Are Great Whites Descended from Mega-Sharks?

- Without Sharks, Food Chain Crumbles

- The Odds of Dying

Image Gallery

Great White Sharks

Fear This

Image Gallery

Great White Sharks