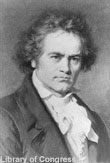

Beethoven's Bones?

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) _ A California businessman said Thursday that skull fragments that once belonged to his great-great-uncle in 19th century Europe very likely came from German composer Ludwig van Beethoven.

Paul Kaufmann made the announcement at the Center for Beethoven Studies at San Jose State University, which helped coordinate forensic testing aimed at authenticating the fragments and determining what killed Beethoven at age 56.

The center already has a lock of the composer's hair, which showed he suffered from lead poisoning among other ailments when he died in 1827. One of Kaufmann's fragments, submitted for testing at the Argonne National Laboratory, showed similarly high levels of lead, Kaufmann said.

Kaufmann, 68, said he found out only in 1986 during a visit with an aging relative in France that some of Beethoven's reputed remains had been passed down through his family for generations. He inherited them in 1990.

The skull fragments _ two large pieces and 11 smaller ones _ were contained in a pear-shaped metal box etched with the name ''Beethoven'' on top. Kaufmann started working with the Center for Beethoven Studies after a writer doing a book on the composer tracked him down in Danville.

The largest two skull fragments are on permanent loan to the center. Director William Meredith called the discovery a major event both for classical music lovers and scientists.

''It puts you in the physical presence of Beethoven's body, and if Beethoven's music means a great deal to you, that is a very powerful thing and has a lot of meaning,'' Meredith said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

DNA tests on the hair and bone samples that could definitively determine that the fragments belonged to Beethoven are under way at the University of Munster in Germany, Meredith said.

''The tests are promising, but they are not finished,'' he said.

Kaufmann said scientists at the university have told him the DNA tests may indicate whether Beethoven inherited a gene that caused him to lose his hearing as a young man.

If the bones are authenticated, they could help establish what killed the composer or at least rule out various theories. Some scientists, for example, have speculated that Beethoven suffered from Crohn's Disease, which causes the bones to swell. But the Kaufmann fragments are of normal size, Meredith said.

The bones made their way into Kaufmann's family in 1863, when Beethoven's body was exhumed, studied and reburied. Kaufmann's great-great-uncle, an Austrian doctor named Romeo Seligmann, is said to have acquired them while making models of the skull, Meredith said.