At Least 320,000 Viruses Lurk in Mammals, Study Finds

From West Nile and Ebola to SARS and HIV, most of the emerging infectious diseases that plague humans today originated in other animals. According to a new estimate, there are at least 320,000 viruses in mammals alone, the vast majority of them awaiting discovery.

Scientists say that collecting data on pathogens that may lurk in wildlife before they jump to humans could help officials detect and stem future outbreaks.

"What we currently know about viruses is very much biased towards those that have already spilled over into humans or animals and emerged as diseases," study author Simon Anthony, of the Center for Infection and Immunity (CII) at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health, said in a statement. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

"But the pool of all viruses in wildlife, including many potential threats to humans, is actually much deeper," Anthony added.

The researchers extrapolated their estimate of virus diversity (or virodiversity, as it's called) by studying the viruses carried by flying foxes that live in the jungles of Bangladesh. These bats are the largest flying mammals with wingspans of up to 6 feet (1.8 meters). Researchers have pointed to the species as the source of the Nipah virus, which can cause deadly brain fevers. The virus first emerged in humans in the 1990s, and according to the World Health Organization, has sparked a dozen outbreaks, all in South Asia.

Researchers took throat swabs as well as feces and urine samples from 1,897 live, healthy-looking flying foxes that they captured and released. In a lab, these samples revealed 55 viruses in nine viral families, only five of them previously known, the team found.

The researchers estimated that the total number of viruses in flying foxes was about 58. If each of the 5,486 known mammals carried 58 unique viruses, there would be around 320,000 viruses in the wild, Anthony and colleagues calculated. The researchers say they are planning follow-up studies in a species of primates in Bangladesh and six species of bats in Mexico to find out if the viral diversity of other animals is indeed comparable with that of the flying fox.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study's authors argue that the cost of studying these viruses would be a bargain compared with the costs of dealing with a single, deadly pandemic.

The surveillance, sampling, and discovery of all 58 flying fox viruses cost $1.2 million, the researchers said. Based on those numbers, they estimated that collecting evidence for undescribed mammal viruses would cost about $6.3 billion. The cost of those efforts could be as low as $1.4 billion if scientists cut rare viruses out of that equation and limited their search to 85 percent of total viral diversity.

For comparison, the SARS outbreak that started in Asia in 2002 was estimated to have had an economic impact of $16 billion, the researchers said.

"We're not saying that this undertaking would prevent another outbreak like SARS," Anthony explained in a statement. "Nonetheless, what we learn from exploring global viral diversity could mitigate outbreaks by facilitating better surveillance and rapid diagnostic testing."

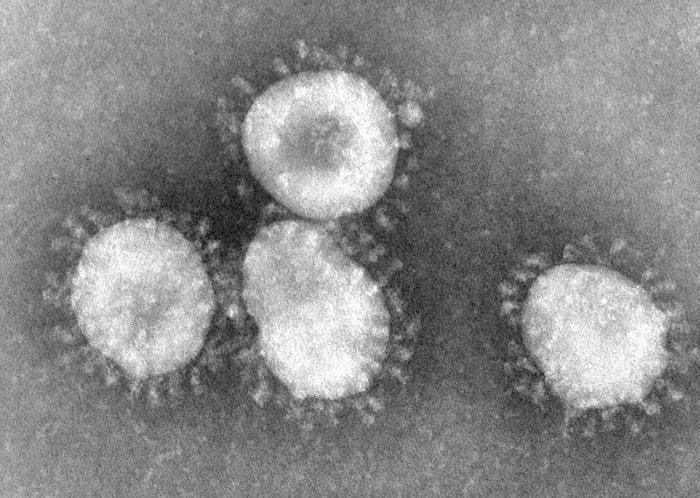

The 2002 outbreak of SARS (or severe acute respiratory syndrome) was caused by a previously unknown coronavirus. It affected more than 8,000 people and killed more than 700 of them before it was contained in 2003. Later research linked the outbreak to an infected cat-like animal called a civet being sold at a market in China, but scientists think the disease may have originally spilled over from bats.

The new research was detailed online today (Sept. 3) in the journal mBio.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.