The Romans occupied modern-day Syria, and before them, the Assyrians, Persians and Akkadians built empires there.

The country is home to ancient Paleolithic fossils, some of the earliest evidence of agriculture and one of the largest troves of cuneiform tablets ever discovered.

"It's probably one of the oldest occupied areas of the Earth," said Emma Cunliffe, an archaeology researcher at Durham University in England, who has published a report documenting archeological damage in Syria. "It's been continuously occupied since before modern man even existed."

Yet hundreds of archaeological sites are imperiled by civil war in Syria; bombing and looting have ravaged some of the richest of these sites; government and rebel forces have occupied ancient castles and bulldozed archaeological mounds created over thousands of years of human occupation. All six of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the country have been damaged, Cunliffe said.

Still, some archaeologists are trying to preserve Syria's heritage. They are talking to government and rebel leaders to protect the most important treasures, and have compiled a list of the key archaeological "no strike" sites that should be protected. [5 Surprising Cultural Facts About Syria]

"This is the heritage first and foremost of the Syrian people, and then of the whole world," said Andrew Moore, the first vice president of the Archaeological Institute of America. "It's therefore in everybody's interests to do all they can to protect these important monuments."

Littered with heritage

As part of the Fertile Crescent, the land that is now Syria has been occupied for tens of thousands of years.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Syria contains some of the world's most beautiful Roman cities, Apamea and Palmyra, as well as a stunning Crusader-era castle called Krak des Chevaliers. Archaeologists have unearthed tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets in the ancient city of Ebla. The country houses the tombs of several of Mohammed's relatives, and its cities of Aleppo and Damascus have been continuously occupied for thousands of years. [The Most Iconic Archaeological Sites in Syria ]

Syria is also littered with thousands of other unstudied archaeological sites.

Historically, people in the region have built mud brick settlements on the ruins of earlier cities. Over thousands of years, a large mound, or tell, forms with layers of each civilization piled atop one another, said Jesse Casana, an archaeologist at the University of Arkansas and the chairman of the American Schools of Oriental Research's Damascus Committee.

Thousands of tells are scattered throughout the country. Most have not been excavated, and even at the most famous digs, archaeologists have barely scratched the surface, Casana said.

Bombing and looting

Bombing has already destroyed some of the most beautiful landmarks in the country. Last year, a 10th-century mosque in the old city of Aleppo was destroyed by bombing, and large parts of the old city, which may be one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in the world, were damaged as well.

But looting is a far bigger problem than direct destruction, Casana said.

Shadowy networks of antiquities smugglers outside of Syria are paying desperate locals to strip archaeological sites of artifacts.

Other evidence suggests that fighters are smuggling artifacts to purchase weapons, Cunliffe said.

At the same time, the civil war has drained resources for protecting archaeological sites. Though civil servants do what they can, their efforts are no match for the chaos.

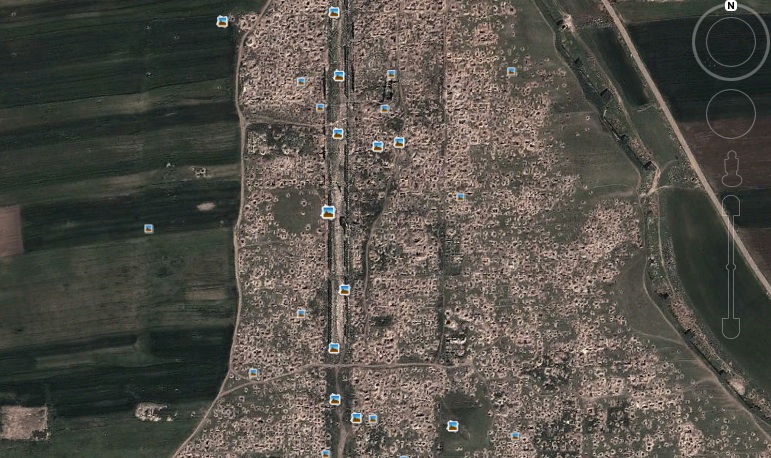

Ebla has been extensively looted and post-civil war satellite imagery has revealed that Apamea, the historic Roman city, has been riddled with holes since the start of the civil war.

"It looks like the surface of the moon," Cunliffe told LiveScience. "In eight months, the looted area exceeded the total excavated area."

Archaeological mounds, meanwhile, serve as attractive outposts for military because of their higher elevation.

"A lot of archaeological sites are being pretty severely damaged by military," Casana told LiveScience. "They build huge bunkers for tanks, or anti-aircraft equipment. They dig huge trenches into them and bulldoze sides of them off."

Protecting future sites

Archaeologists are doing what they can to protect the most famous sites. They have spoken with rebel and government forces about protecting those sites.

And Organizations such as Blue Shield have documented damage using satellite imagery and have compiled lists of hundreds of the most valuable sites.

The U.S. government has added those sites, along with places such as hospitals and schools, to its "no strike" list. If the United States does pursue military strikes, hopefully, the potential for damage will be limited, Casana said.

Still, there's no undoing the damage that's already been done. The site that Casana once studied, Tell Qarqur in Western Syria, has been badly damaged.

"They put tanks on my site," Casana said. "I'm sure they're using my excavation trenches as toilets and digging holes in the thing. It's pretty depressing."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.