How California's Rim Fire Grew So Big

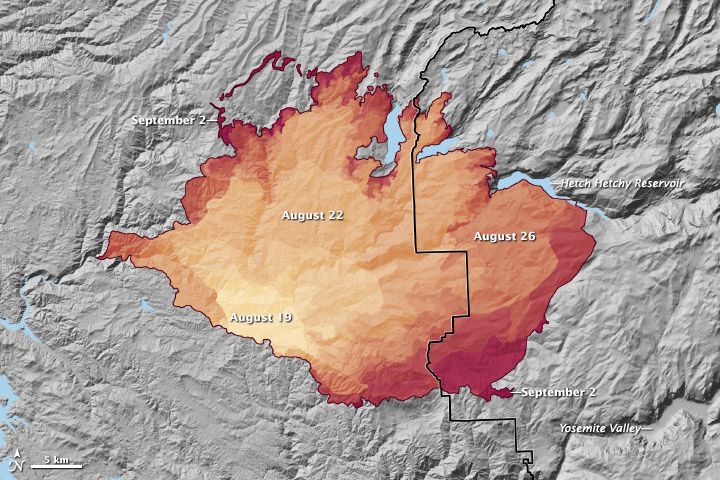

During Labor Day weekend, firefighters saved some of Yosemite National Park's most popular spots from California's raging Rim Fire.

Two giant sequoia groves survived the flames, as did the Big Oak Flat entrance on Highway 120, where more than 60,000 visitors pass through each month in the summer. High humidity and light rainfall helped firefighters contain 75 percent of the Rim Fire by Tuesday morning (Sept. 3), the U.S. Forest Service said.

That was some much-welcomed good news on the Rim Fire, which is now California's fourth largest wildfire since 1932 and the largest forest fire ever recorded in the Sierra Nevada, the granite mountains that run from north to south along the state's eastern fringe.

Researchers predict that wildfires will tear through the western forests more often as a result of climate change: Drought and higher temperatures in the western United States will increase fire frequency by drying and warming landscapes.

This year, however, even with the Southwest's prolonged drought, the total acreage burned is down. Last year, 67,774 wildfires torched 9.3 million acres (37,635 square kilometers). This year, 3.8 million acres (15,378 square km) have burned through Aug. 30, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. But the Rim Fire was still a huge fire, though it reached such a size because of different manmade causes.

Instead of drought fueling the flames, decades of fire suppression and other human-caused changes, such as grazing and replanting, were behind the rapid spread of the Rim Fire, fire experts say. To see the effect, one has just to look at how quickly the wildfire raced through the Stanislaus National Forest, compared to its halting progress in Yosemite National Park.

Early on, in the Stanislaus National Forest next to Yosemite, nearly half of the Rim Fire's 368 square miles (953 square km) burned in the first two days. The U.S. Forest Service prefers to thin trees or conduct controlled burns instead of letting forest fires run their course. But in recent years, reduced funding for preventive firefighting has hampered both thinning and prescribed burns. In the Groveland district, birthplace of the Rim Fire, the forest service had eight fire control projects planned, Reuters reported. [Yosemite Aflame: Rim Fire in Photos]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As much as possible, the National Park Service lets naturally sparked fires burn, which meant there was less underbrush and fewer small trees to fuel the fire once it reached Yosemite, so the blaze slowed.

"The Rim Fire is now burning into areas of northwestern Yosemite National Park that have had several past managed wildfires. I believe these past fires will have a big influence on the Rim Fire and if the previous area has been burned in 10 or less years, the fire will go out on its own," Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an email interview.

Fueling the flame

The Rim Fire's change in speed and intensity is dramatic evidence that fire management is as important as climate change when it comes to wildfires, and that the two factors could combine in the future, with dire consequences.

"My view is unless we get ahead of the fuels/restoration problem in forests that once experienced frequent fire, wildfires influenced by climate change will burn them at severities and spatial scales that will not conserve forests into the future," Stephens told LiveScience.

Tree ring studies show California's mountain forests evolved with frequent, low-intensity fires, every 10 or 15 years. The fires burned low to the ground and rarely were hot enough to kill big trees, such as ponderosa pines and giant sequoias. In these forests, the tall, long-lived trees drop their lower limbs, so fires can't crawl up into their crowns.

Now, after a century of fire suppression, grazing, logging and replanting, many of California's mountain forests are dense and overgrown, with too many trees crowded together and dead, dry wood and debris piled up on the forest floor, according to studies by fire ecologists such as Stephens. Fires today burn hotter and higher up into the big trees (so-called crown fires).

As the Rim Fire incinerated parts of Stanislaus Forest, Stephens evacuated a four-person research crew studying an old-growth stand of trees that included sugar pine, incense cedar, ponderosa pine and Douglas fir with diameters up to 4 feet (1.2 meters) thick, he said.

"I think this whole place is now gone," Stephens said. "I believe that climate change is drying out forests earlier and temperatures are up. However, if fuels treatments had been used in this area we would not have had the tree mortality that has probably occurred."

The fire will provide scientists with a trove of data on forest fires. The flames raced through experimental forests studied for more than a century and a variety of landscapes, such as recently replanted burns and untouched forests. Such data will help better inform forest management practices in the future, particularly under a changing climate.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.