A huge, federally funded project to map the human brain is incomplete because it ignores some of the brain's star players, a new editorial argues.

The $100 million Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, which is slated to begin in 2014, should map not only neurons, the brain cells that send electrical signals, but also the supportive cells in the brain called glia, according to the editorial published today (Sept. 4) in the journal Nature.

"The fact is that the greater mysteries in the brain right now are what the non-neuronal cells are doing," said author Doug Fields, a neuroscientist at the National Institutes of Health. "Neurons are only 15 percent of the cells in the brain."

Mysterious purpose

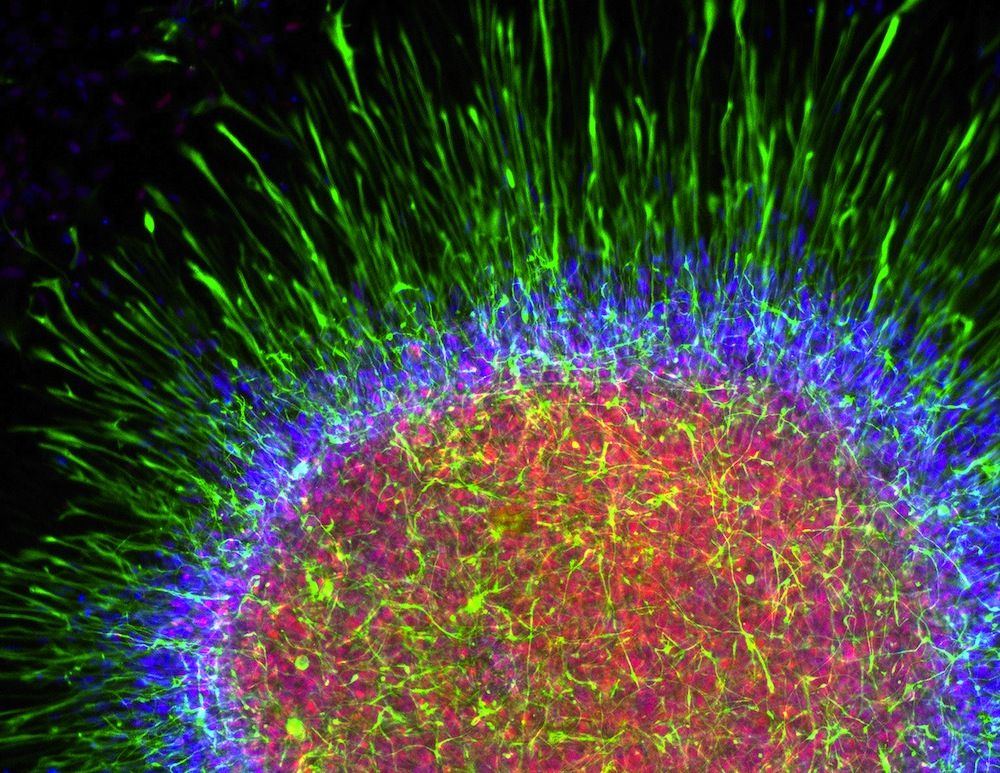

Though neurons get the most attention, there are millions of other brain cells that have critical functions. These supportive cells, called glia, are often the first responders when the brain is injured. [Gallery: Slicing Through the Brain]

Research has suggested that glia play a role in a host of diseases. Glial dysfunction is implicated in chronic pain, psychiatric illnesses such as depression, schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder and degenerative diseases such as Lou Gehrig's disease and multiple sclerosis. Even HIV-related dementia occurs when the virus infiltrates glial cells (the virus cannot penetrate neurons).

But relatively little is known about how glial cells are connected to each other, or what roles they play in the healthy brain.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Flawed but important

The new brain-mapping initiative is important but flawed, Fields said. That's because the goal is to map all of the connections between neurons, under the assumption that such a map could reveal the mysteries of the brain. None of the focus is on developing technologies to map connections between glia, or between neurons and glia.

One type of glial cell, called astrocytes, send signals to each other using brain chemicals called neurotransmitters, the same chemicals that are found at the junctions between neurons.

As such, astrocytes can sense the signals sent between neurons, and may even stop or amplify those signals.

"They are controlling the information flow," Fields told LiveScience.

Normally functioning glial cells may clear out beta-amyloid, the tangled proteins that accumulate in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease. So glia may be playing a critical role in the formation and maintenance of memory.

Creating a brain map of only the networks between neurons would leave out critical — and the most mysterious — elements in the network, Fields argued.

"We should be mapping the uncharted regions first," Fields said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.