Dying stars that are among the most beautiful objects in the universe tend to line up across the night sky, and astronomers aren't sure why.

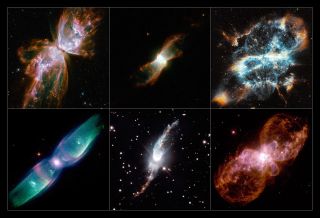

These "cosmic butterflies" — actually a certain type of planetary nebula — all have their own formation histories, and they don't interact with each other. But something is apparently making them dance in step, scientists using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and the European Southern Observatory's New Technology Telescope (NTT) have discovered.

"This really is a surprising find and, if it holds true, a very important one,"study lead author Bryan Rees, of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. "Many of these ghostly butterflies appear to have their long axes aligned along the plane of our galaxy. By using images from both Hubble and the NTT we could get a really good view of these objects, so we could study them in great detail." [Strange Nebula Shapes: What Do You See? (Photos)]

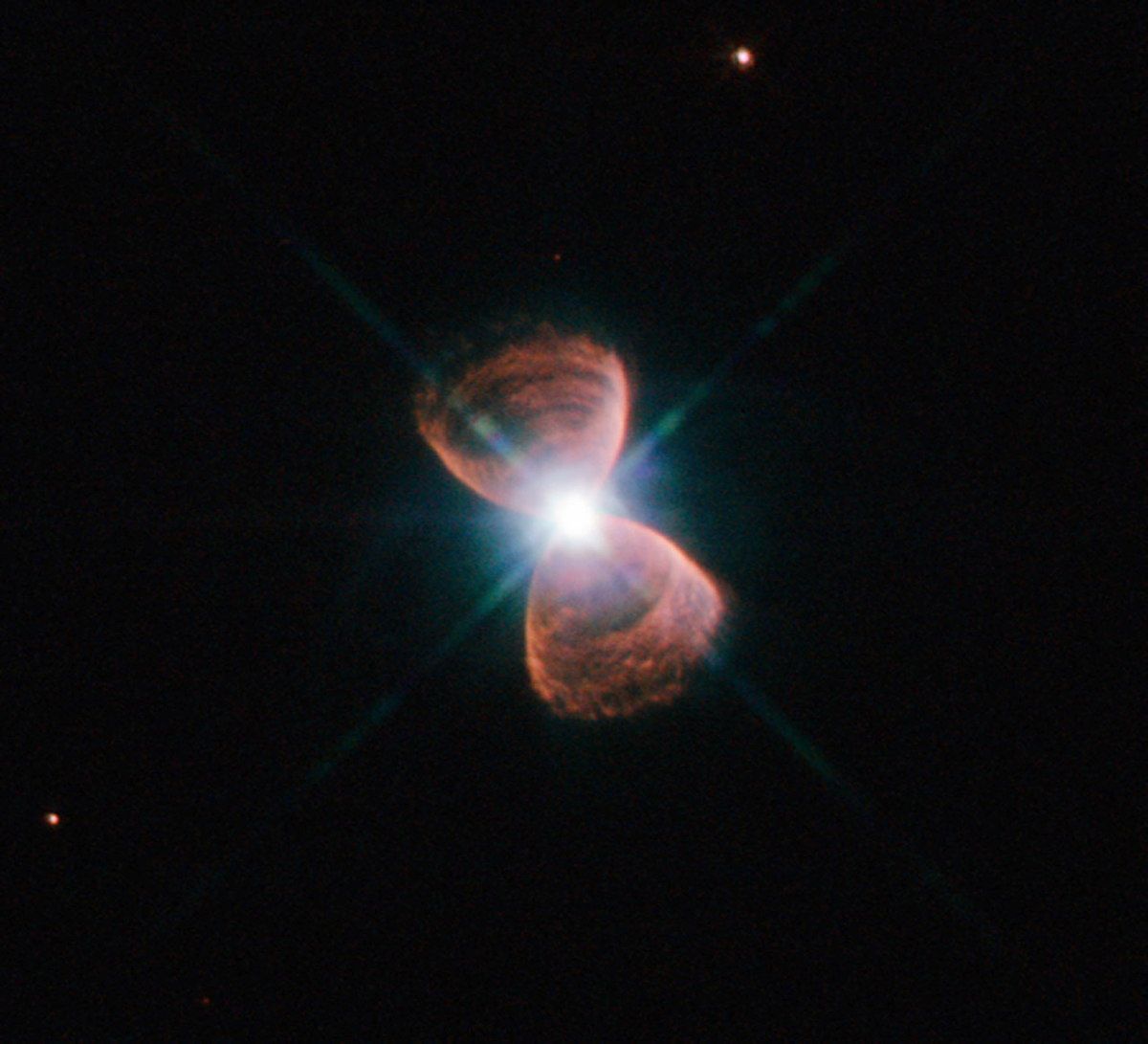

In the final stages of their lives, stars like our own sun puff their outer layers into space, creating strange and striking objects known as planetary nebulas. (No planets are necessarily involved. The term was coined by famed astronomer Sir William Herschel to describe celestial bodies that appeared to have circular, planet-like shapes when viewed through early telescopes.)

Rees and co-author Albert Zijlstra, also of the University of Manchester, studied 130 planetary nebulae in the central bulge of the Milky Way galaxy.

They found most of these objects to be scattered more or less randomly across the sky, but one type — the bipolar nebulae, which have distinctive butterfly or hourglass shapes that are thought to result when jets blast material away from a dying star perpendicular to its orbit — showed a surprising alignment.

"The alignment we're seeing for these bipolar nebulae indicates something bizarre about star systems within the central bulge,"Rees said. "For them to line up in the way we see, the star systems that formed these nebulae would have to be rotating perpendicular to the interstellar clouds from which they formed, which is very strange."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Faraway bipolar nebulae display this predilection much more than nearby cosmic butterflies do, the researchers said. They suspect that the orderly behavior may have been caused by strong magnetic fields present when the galaxy's central bulge was forming.

But little is known about the characteristics of the Milky Way's magnetic fields in the distant past, so the planetary nebula alignment remains mysterious for now.

"We can learn a lot from studying these objects,"Zijlstra said in a statemnt. "If they really behave in this unexpected way, it has consequences for not just the past of individual stars, but for the past of our whole galaxy."

The new study will appear in an upcoming issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.