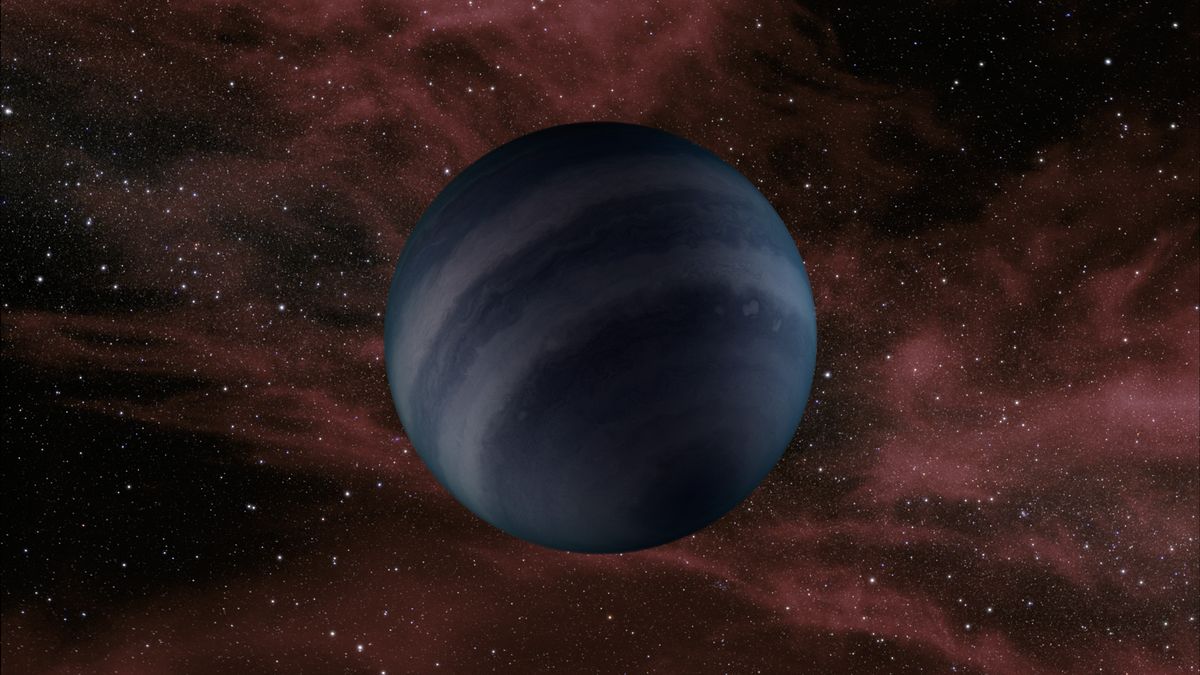

Brown Dwarfs: Strange 'Failed Stars' Only as Hot As Your Oven

The best look yet at mysterious brown dwarfs, strange cosmic oddities that blur the lines between stars and planets, has revealed just how large and cold they really are, scientists say. In fact, the weird "failed stars" only get as hot as your kitchen oven.

The new discovery may shed light on the formation and evolution of distant alien worlds, researchers added.

Starlike bodies known as brown dwarfs are often billed as failed stars because they are larger than planets, but too small to trigger nuclear fusion and ignite into the brilliance of a full-fledged star.

As such, brown dwarfs have only what little heat they are born with. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

These new findings suggest the coldest brown dwarfs are between about 260 and 350 degrees Fahrenheit (125 and 175 degrees Celsius), with masses five to 20 times greater than the size of Jupiter. The temperature of the sun, for example, is about 10,000 F (5,500 C) at its surface.

"These objects we were studying were suspected to be colder than anything else that had previously been discovered in the solar neighborhood," said study lead author Trent Dupuy, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. Several hundred have been detected to date.

Chilly brown dwarf science

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists discovered the coldest type of brown dwarfs two years ago, which theoretical models suggested could at times be even cooler than the human body.

"Astronomers are always looking for colder and colder free-floating, starlike objects," Dupuy told SPACE.com. "One key reason for this is that their atmospheres have similar temperatures to many of the gas giant planets that have been discovered orbiting stars other than the sun. So they are like little laboratories where you can study atmospheric physics relevant to extrasolar planets, but without the glare of their host star."

However, the dim and distant nature of these cold brown dwarfs made it difficult to confirm just how far away, large, bright and cold they actually were.

"Because they were not like anything that had been seen before, we couldn't really be sure what we were dealing with," Dupuy said.

Now, using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, astronomers have measured the precise distances to eight cold brown dwarfs. This, in turn, helped them calculate just how bright, cold and massive they are.

The researchers analyzed how the distance of these brown dwarfs appeared to vary in relation to more distant background stars as the Earth completed an orbit around the sun. This helped triangulate the position of these brown dwarfs. These changes are very subtle, requiring the scientists to patiently gather data for a year.

Once the astronomers knew how far away these brown dwarfs were, they could deduce how bright and cool they must be for their light and heat to be detected. Based on this data, the researchers could then model how massive they were.

"It is remarkable that astronomers were able to correctly predict that this new type of brown dwarf is in fact colder than anything known before," Dupuy said. "But our study also showed that theoretical models for such cold, low mass objects are far from perfect yet. We found that the temperatures are significantly higher than models predicted — their surfaces are not room temperature — even though they are indeed the coldest free-floating objects we know about."

More brown dwarf strangeness

Intriguingly, the light spectra of these cold brown dwarfs does not correspond with their temperature. Since the spectrum of light from a planet or star reflects its chemical makeup, this suggests the atmospheric chemistry of cold brown dwarfs is no longer driven primarily by its heat, as is the case for warmer brown dwarfs.

"Instead, other processes like convective mixing and the strength of gravity at the surface seem to take equally prominent roles as temperature," Dupuy said.

In the coming years, the researchers may analyze three times more cold brown dwarfs.

"With many more objects, we'll hopefully be able to understand more clearly what parameters are really most important in setting the atmospheric chemistry," Dupuy said.

Dupuy and his colleague Adam Kraus detailed their findings online today (Sept. 5) in the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.