Interstellar Wind Changes Reveal Glimpse of Milky Way's Complexity

Shifting cosmic winds suggest that our solar system lives in a surprisingly complex and dynamic part of the Milky Way galaxy, a new study reports.

Scientists examining four decades' worth of data have discovered that the interstellar gas breezing through the solar system has shifted in direction by 6 degrees, a finding that could affect how we view not only the entire galaxy but the sun itself.

"The shift in the wind is evidence that the sun lives in an evolving galactic environment," study lead author Priscilla Frisch of the University of Chicago told SPACE.com via email. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy]

The winds of change

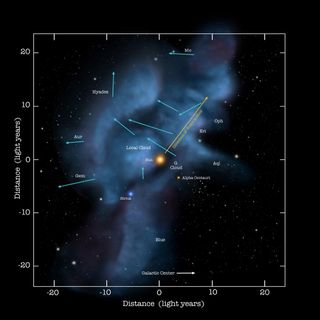

Charged particles stream off the sun to form a huge invisible shellaround the solar system called the heliosphere. Outside of this shell lies the Local Interstellar Cloud (LIC), a haze of hydrogen and helium approximately 30 light-years across.

The LIC is wispy, featuring just 0.016 atoms per cubic inch (0.264 per cubic centimeter) on average. LIC gas tends to be blocked by the heliosphere, but a thin stream makes it past the sun's magnetic field at the rate of 0.0009 atoms per cubic inch (0.015 atoms per cubic cm), researchers said.

"Right now, the sun is moving through an interstellar cloud at a relative velocity of 52,000 miles per hour (23 kilometers per second)," Frisch said. "This motion allows neutral atoms from the cloud to flow through the heliosphere — the solar wind bubble — and create an interstellar 'wind.'"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

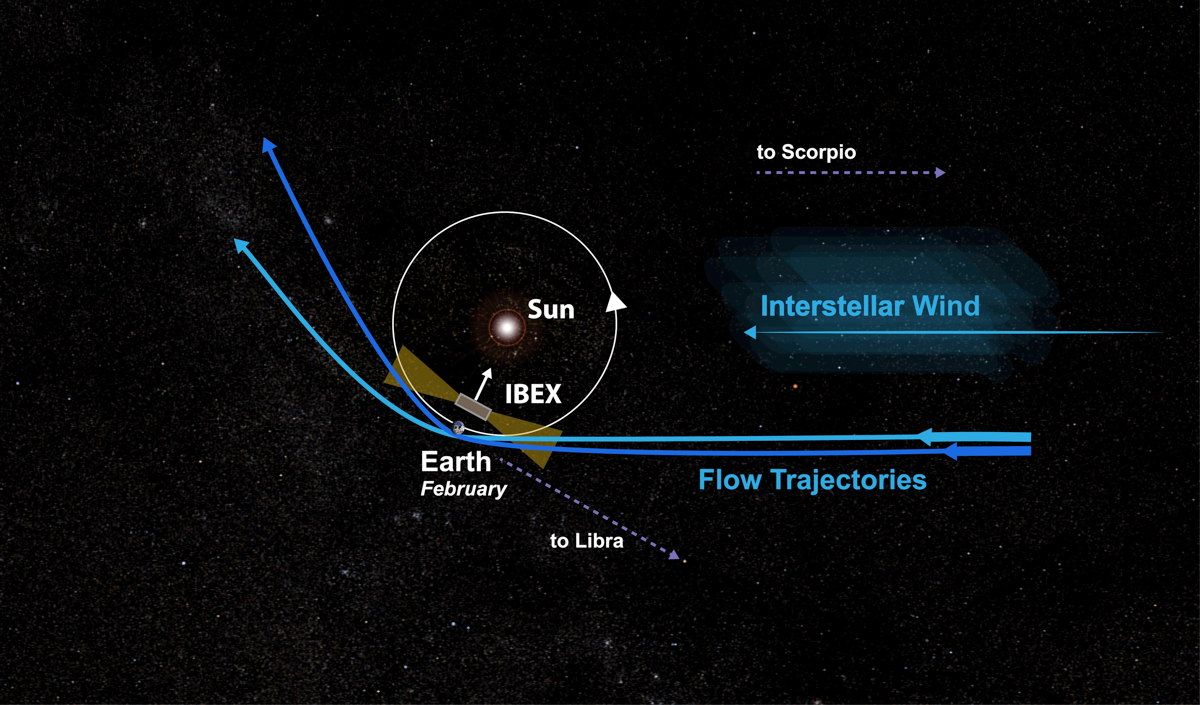

In 2012, three papers citing measurements by NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) spacecraft showed that the wind has changed slightly over the past decade.

Frisch and her team were intrigued, and they began to wonder just how far back the difference extended. Studying data gathered by a number of spacecraft — IBEX, the joint European Space Agency/NASA Ulysses probe and several craft from the 1970s, including NASA's Mariner 10 and the Soviet research satellite Prognoz 6 — the team found that, over the course of 40 years, the wind had shifted by 6 degrees.

What's causing this change in direction? According to Frisch, it may be related to turbulence in the interstellar cloud around the solar system.

"Winds on Earth are turbulent, and other data show that interstellar clouds are also turbulent," she said. "We find that the 6-degree change is comparable to the turbulent velocity of the surrounding cloud on [the] outside of the heliosphere."

Wide-reaching effects

Interstellar winds stream in from the direction of the constellation Scorpius, almost perpendicular to the sun's path through the galaxy. As the winds interact with the sun, they create a distinctive feature.

"Helium is gravitationally focused to create a trail of helium known as the 'focusing cone' behind the sun as it moves through space," Frisch said.

The dense cone makes the particles easier to study as they pack in behind Earth's star.

The changing wind could have implications that go beyond understanding the region surrounding the solar system. It could also affect studies of the charged particles streaming off the sun.

"When we try to understand the past and present heliosphere, we can no longer assume that the heliosphere changes only because of the solar wind," Frisch said. "Now we have evidence that changes in the interstellar wind may be important."

The new study was published online today (Sept. 5) in the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.