Bermuda Triangle Earthquake Triggered 1817 Tsunami

A "tidal wave" violently tossed ships docked along the Delaware River south of Philadelphia at about 11 a.m. ET on Jan. 8, 1817, according to newspapers of the time. Turns out, that tidal wave was actually a tsunami, launched by a powerful magnitude-7.4 earthquake that struck at approximately 4:30 a.m. ET near the northern tip of the Bermuda Triangle, a new study finds.

The study links the tsunami to a known Jan. 8, 1817, earthquake. The temblor shook the East Coast from Virginia south to Georgia, where the seismic waves made the State House bell ring several times. Based on archival accounts of the 1817 shaking, geologists had gauged the quake's size at magnitude 4.8 to magnitude 6. Now, with new geologic detective work and computer modeling of the tsunami, researchers have considerably revised the earthquake's size. A magnitude-7.4 quake releases almost 8,000 times more energy than a magnitude-4.8 earthquake.

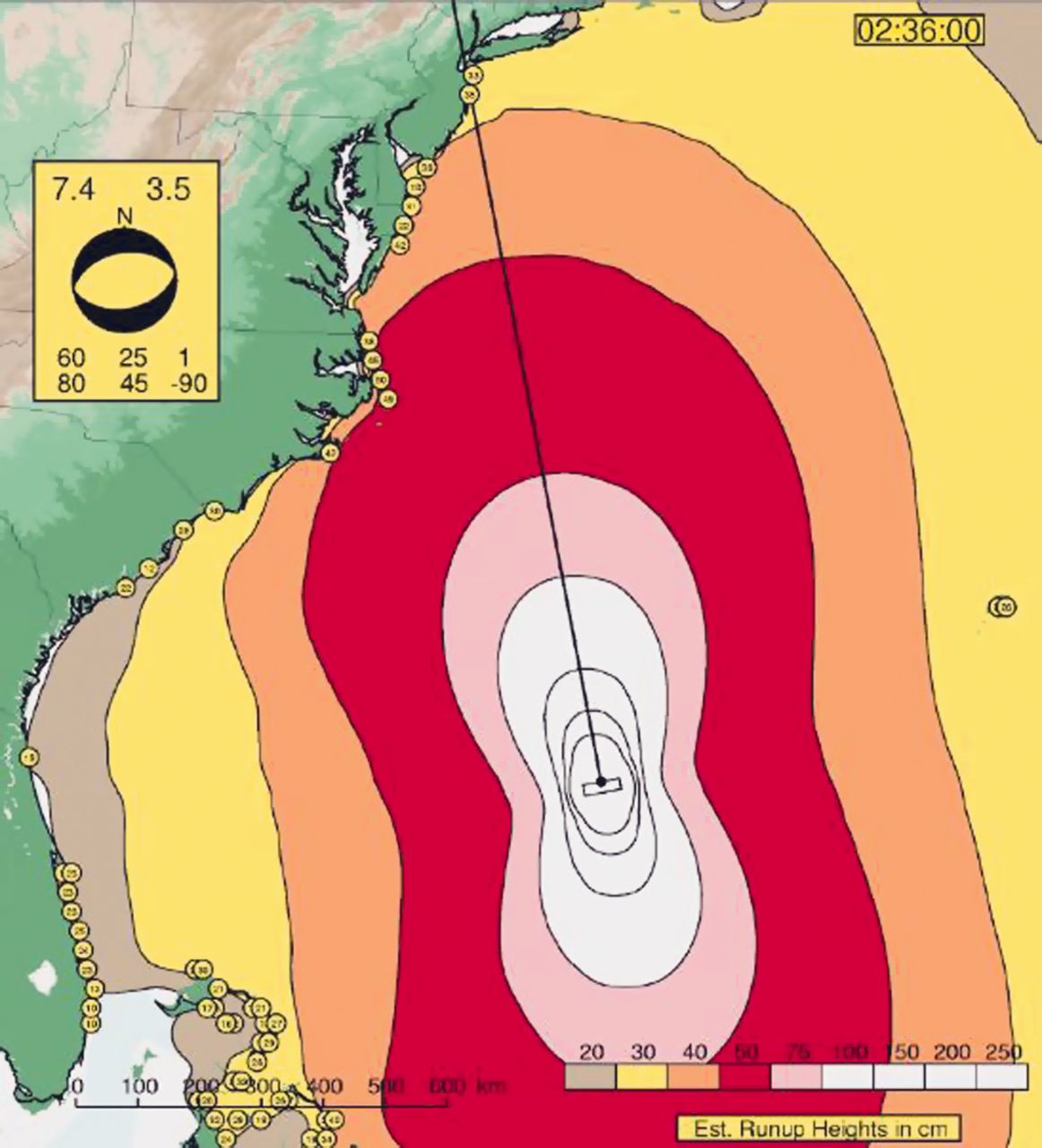

The size and location, or epicenter, of the 1817 earthquake has never been pinned down so closely before. U.S. Geological Survey research geophysicist Susan Hough and her colleagues zeroed in on the source from newly uncovered archival records, looking at where the shaking was strongest. But they weren't sure about the tsunami link: The 11 a.m. arrival time seemed too late for a 4:30 a.m. earthquake. So they created a computer model of the tsunami, testing different locations and magnitudes. The best fit to force a foot-high (30 centimeters) wave up the mouth of Delaware Bay by about 11 a.m. was a magnitude-7.4 earthquake offshore of South Carolina.

"That was the eureka moment," Hough told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. "Darned if that wave doesn't hit the Delaware River and slow way down."

A spooky source

The foot-high tsunami wave started about 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) south of Delaware Bay and 400 to 500 miles (650 to 800 km) offshore of South Carolina, according to the study, published in the September/October issue of the journal Seismological Research Letters. That's smack on the northwestern limb of the so-called Bermuda Triangle. [Gallery: Lost in the Bermuda Triangle]

"When we started to say, 'OK, it's the Bermuda Triangle Fault,' that did not go over well," Hough said. "Some of our colleagues didn't want us to get into all this hooey."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

No obvious culprit jumps out of the seafloor topography, such as a linear feature that could be an earthquake-causing fault, Hough said. But according to ship records, the sea above the temblor's likely epicenter trembled for several years. Earthquakes can be felt at sea, and ship captains reported shaking before and after Jan. 8, 1817, that could have been foreshocks and aftershocks, the researchers said. Ships in the area also rocked or shook from earthquakes in 1858, 1877 and 1879.

"It was interesting enough to mention," Hough said. "People were feeling earthquakes on ships, and earthquakes can damage early ships. Maybe this is part of the thinking that there were strange things going on in that part of the ocean."

East Coast tsunami risk

However, Hough's goal isn't to solve the mystery of the Bermuda Triangle, but rather to fill in the gaps in the East Coast's earthquake history. Before the new study of the 1817 earthquake, the only other big offshore temblor in recorded history was the 1929 Grand Banks quake, a magnitude-7.2 off the south coast of Newfoundland that unleashed a deadly tsunami.

"Grand Banks has been seen as an outlier or a fluke event," Hough said. "If our interpretation is correct, it points to a more distributed [seismic] hazard. Maybe we should expect this kind of earthquake all along the continental shelf."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.