Faces of Ancient Mexico Revealed in Skulls

Editor's note: This article was updated on Thursday (Sept. 12) at 5:00 p.m. ET.

Long before the arrival of European colonists, the indigenous people of Mexico showed wide variation in their facial appearance, a diversity that perhaps has not been fully appreciated, a new study of skulls suggests. Researchers hope their findings might help forensic investigators acurately identify people who are killed attempting to cross the U.S. border.

"There has long been a school of thought that there was little physical variation prior to European contact," study researcher Ann Ross, a forensic anthropologist at North Carolina State University, said in a statement. "But we've found that there were clear differences between indigenous peoples before Europeans or Africans arrived in what is now Mexico."

In other words, the researchers say there is not one phenotype, or bundle of physical characteristics, for all native people — contrary to earlier studies that looked at hair color, skin color and body form, and concluded that physical variation among indigenous Mexican people was modest.

Through some forensic sleuthing, Ross and colleagues discovered differences between geographically separate groups in the shapes in their cheekbones, the bones surrounding their eyes and the bridge of their nose, before they ever made contact with Westerners.

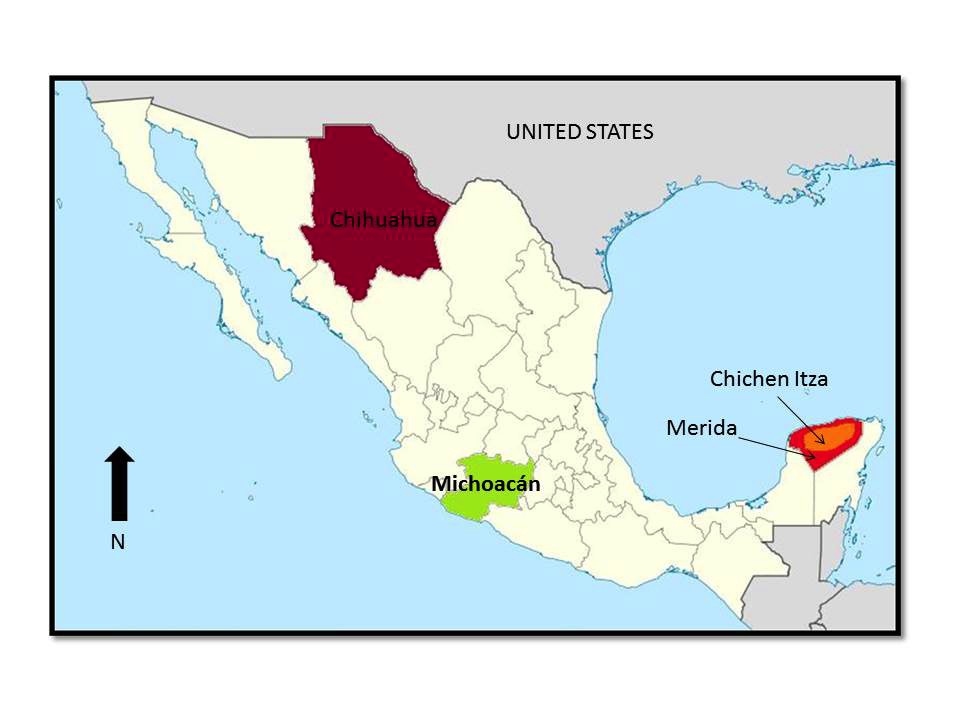

The researchers examined dozens of pre-Columbian skulls found in Mexico, including bones from the iconic Maya city of Chichen Itza in the Yucatan Peninsula and remains of people from the Tarascan culture much farther inland, in the Michoacan state. The team also looked at the skeletons of people of Spanish origin, African Americans and contemporary Mayans for comparison. [Photos: 'Alien' Skulls from Mexico Reveal Odd, Ancient Tradition]

The researchers focused on facial features rather than skull shapes, because some ancient groups in Mexico practiced skull modification, Ross told LiveScience Wednesday evening. Archaeologists have turned up evidence showing that some cultures bound the heads of children so that they would be warped into alien-like shapes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Compared with the Spanish and African groups, the Native American groups in Mexico generally had broader, shorter faces, Ross said.

But a statistical analysis of the facial landmarks on the skulls showed differences within the indigenous populations in different parts of Mexico. The skulls in the Michoacan sample were especially distinct from the other Mexican samples, which the researchers believe is in line with previous findings that suggest the Tarascans were a culturally and linguistically distinct group that may have been more aligned with other groups in South America.

"This makes it clear that there was no clear, overarching phenotype for indigenous populations," another study researcher Ashley Humphries, a doctoral student at the University of South Florida, said in a statement. "All native peoples did not look alike."

Ross said she has already published a study on skull variation in ancient Peru and she is hoping that a database of these morphologies could help identify victims of violence near the U.S.-Mexico border.

"We have a huge crisis in the United States of border-crosser deaths," Ross told LiveScience. "A lot of these people come from Mexico, and really all over Latin America, but the morphologies that are used to establish identity are not well understood."

"If we know the variation that is going on in Mexico and Mesoamerica, hopefully we'll be able to help identify the origin of border-crossing fatalities," Ross added.

Their findings were detailed this month in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.