How Crocs Survived in Dinosaur-Dominated World

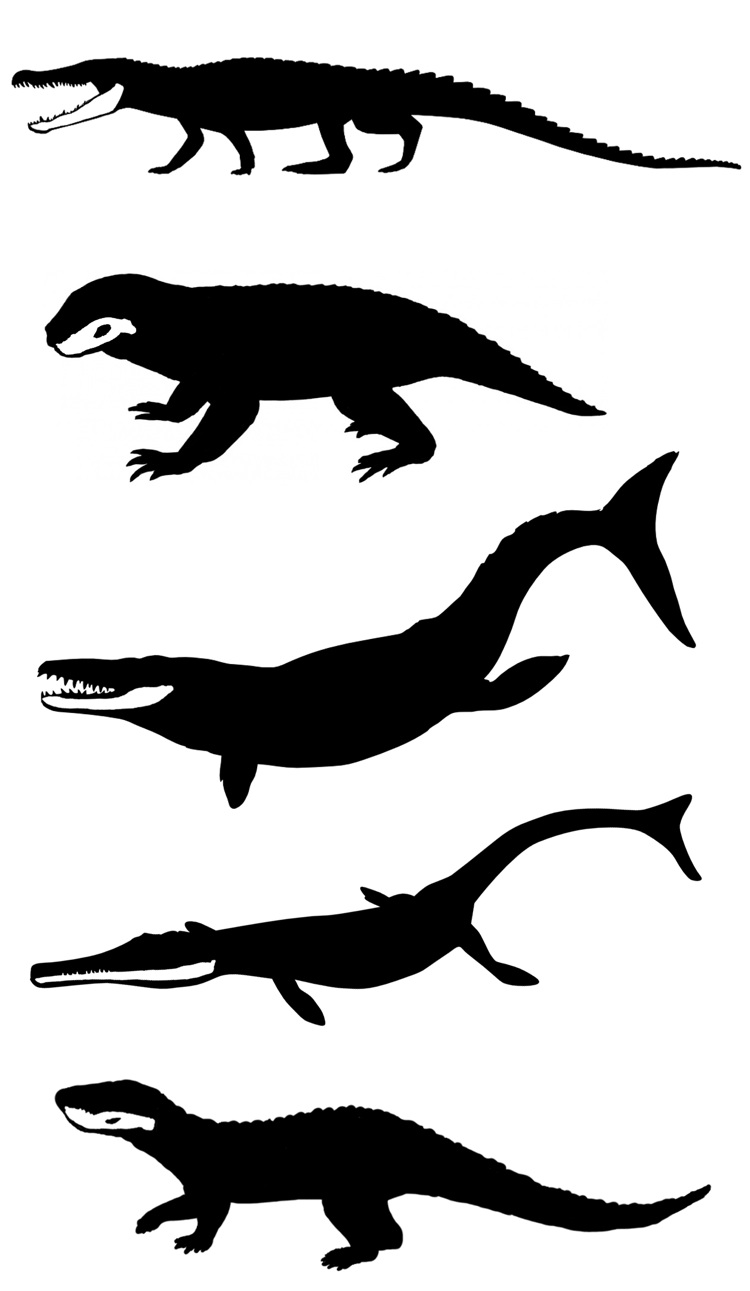

Ancient crocodilians once evolved lifestyles unlike anything seen today in their modern relatives, including plant-eating herbivores, small insect-eating runners, marine fish eaters and giant carnivores on both land and in the sea. There were even crocs whose feeding mimicked that of modern killer whales.

Now, researchers have uncovered details on how this extraordinary diversity evolved so ancient crocodilians could survive in a world dominated by dinosaurs.

While modern crocodiles mostly live in freshwater habitats and feed on mammals and fish, during the Mesozoic Era (about 250 million to 65 million years ago) — the era often called the Age of Reptiles — a "lost world" of dazzling crocodilian variety existed. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

"The ancient relatives of today's crocodiles have an interesting and relatively unknown history," said researcher Thomas Stubbs, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Bristol in England. "During the time of the dinosaurs, they [crocodilians] were very different creatures to the ones we are familiar with today."

To uncover the roots of this diversity, researchers have analyzed, for the first time, how the jaws of ancient crocodiliansevolved to enable these animals to survive in vastly different environments.

"Our study is the first to look at major patterns across many different ancient crocodile groups over such a long time interval," Stubbs told LiveScience.

Stubbs and his colleagues examined patterns in how the lower jaws in more than 100 ancient crocodilians varied in shape and function over the entire course of the Mesozoic.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We were curious how extinction events and adaptations to extreme environments during the Mesozoic, a period covering over 170 million years, impacted the feeding systems of ancient crocodiles, and to do this, we focused our efforts on the main food-processing bone, the lower jaw," researcher Stephanie Pierce of the Royal Veterinary College in London said in a statement.

A key event in crocodilian evolution was apparently the end-Triassic extinction event about 200 million years ago, which wiped out roughly half of all species. Until that disaster, mammallike creatures known as therapsids were actually more numerous than the ancestors of both crocodilians and dinosaurs, known as archosaurs.

After the devastating end-Triassic extinction event, crocodilians invaded the seas and evolved jaws primarily built to efficiently swim in the water to catch agile prey such as fish.

Ancient crocodiles also evolved a great variety of lower jaw shapes during the Cretaceous Period about 145 million to 65 million years ago as they adapted to a diverse range of niches and environments alongside the dinosaurs, including eating plants.

The researchers were surprised to discover that by the Cretaceous, while the lower jaws of crocodilians changed much in shape, they did not show a great deal of variety in function. "This may be because major adaptations were found in other areas of their anatomy, such as armadillolike body armor," Stubbs said.

In the future, the researchers would like to extend the study to the present day, "to see how crocodiles went from being so diverse and anatomically varied to having relatively restricted lifestyles," Stubbs said.

The researchers detail their findings online Sept. 11 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.