Strange Case of 'Hyper Empathy' after Brain Surgery

In a strange case, a woman developed "hyper empathy" after having a part of her brain called the amygdala removed in an effort to treat her severe epilepsy, according to a report of her case. Empathy is the ability to recognize another person's emotions.

The case was especially unusual because the amygdala is involved in recognizing emotions, and removing it would be expected to make it harder rather than easier for a person to read others' emotions, according to the researchers involved in her case.

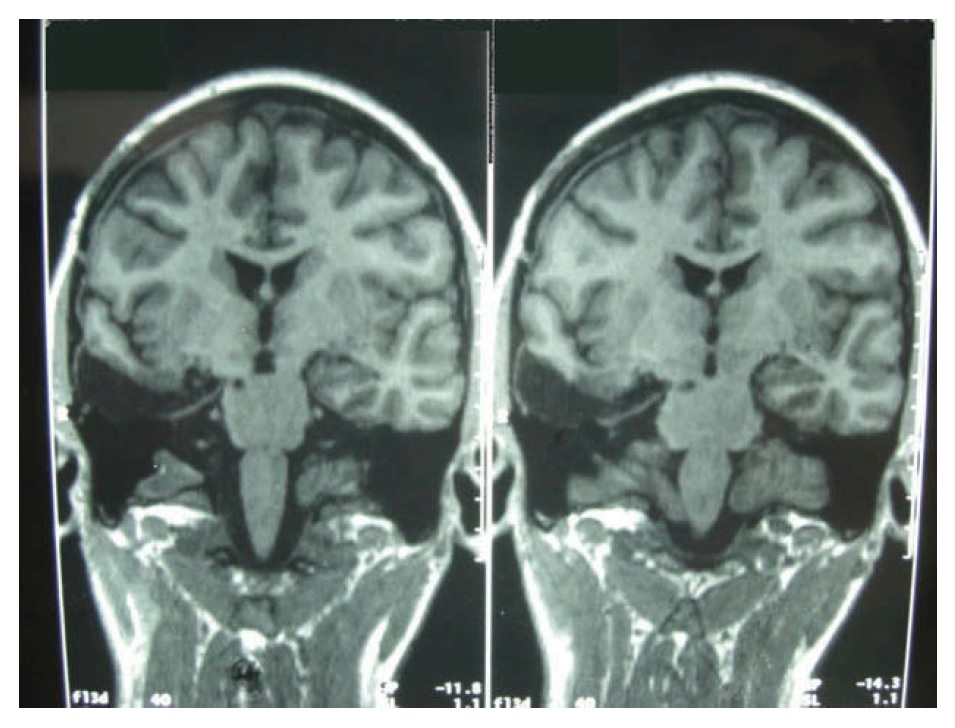

During the woman's surgery, doctors removed parts of her temporal lobe, including the amygdala, from one side of the brain. The surgery is a common treatment for people with severe forms of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) who don't respond to medication.

After the surgery, the seizures she had suffered multiple times a day stopped. But the woman reported a "new, spectacular emotional arousal," that has persisted for 13 years to this date, the researchers said. [9 Oddest Medical Cases]

Although patients with epilepsy treated with surgery have been known to experience new psychological issues afterward, such as depression or anxiety, "the case of this patient is surprising because her complaint is uncommon, and fascinating: hyper empathy," said Dr. Aurélie Richard-Mornas, a neurologist at University Hospital of Saint-Étienne in France, who reported the case.

Her empathy seemed to transcend her body -- the woman reported feeling physical effects along with her emotions, such as a "spin at the heart" or an "esophageal unpleasant feeling" when experiencing empathic sadness or anger. She reported these feelings when seeing people on TV, meeting people in person, or reading about characters in novels, the researchers said.

She also described an increased ability to decode others' mental states, including their emotions, the researchers said. Her newly acquired ability to empathize was confirmed by her family, and she performed exceptionally well in psychological tests of empathy, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The case, published Aug. 14 in the journal Neurocase, is the first in the scientific literature describing this kind of emotional change after removing parts of the temporal lobe, Richard-Mornas said. [Image: Patient's MRI Scan after Surgery]

Kinds of empathy

Psychologists define two major forms of empathy: emotional and cognitive.

"Emotional empathy refers to feeling another person's emotion," Richard-Mornas said. "While cognitive empathy is the ability to adopt the other person's point of view, or 'put oneself in his/her shoes,' without necessarily experiencing any emotion."

It's not exactly clear how the human brain is able to understand and re-create the mental and emotional state of another person, but it appears that not everyone is equally good at it. For example, people with autism are thought to have difficulty understanding other people's intentions, and psychopaths are thought to show a lack of empathy, being unable to experience the emotional reaction people usually have when seeing another person in distress.

In studying the woman with hyper empathy, the researchers evaluated her psychological condition with a series of standard tests, and found that her mental health appeared normal.

The researchers also analyzed how the woman responded to a questionnaire aimed at measuring empathy, made of items such as "I am good at predicting how someone will feel" and "I get upset if I see people suffering on news programmes." She also completed a test of recognizing the emotions in 36 photographs of only people's eyes, and her scores were compared to those of 10 women who served as controls.

Her performance in empathy tests was above average, and her score on the eye test was significantly higher than that of the controls, according to the researchers.

The missing amygdala

The amygdala is a small almond-shaped structure, sitting deep in the temporal lobe. It appears to be involved in social interaction, and is thought critical for quickly evaluating and responding to emotional stimuli, such as a frightening predator or a sad face.

The new case comes in contrast to previous observations of people who endured damage to the amygdala and suffered emotional deficits. In a 2001 study involving 22 people who had parts of their temporal lobe removed, researchers found that people with more extensive damage to the amygdala performed worse in learning emotional facial expressions.

However, in the absence of the amygdala, other brain regions, and perhaps newly organized connections among them, may be responsible for driving stronger empathy, the researchers of the new case report said.

"Neural substrates of complex emotions such as empathy are poorly understood," said Dr. Joseph Sirven, a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Arizona, who was not involved with the case.

"What we are finding is that there is not just one anatomical correlate of emotion. Rather, complex emotions like empathy, hope, etc., are likely to occur as a complex interplay from a number of areas in the brain and the amygdala is one," Sirven said.

The woman's case suggests it is possible to have unexpectedly re-organized neural networks after this kind of surgery, the researchers said, and may have lessons for a better understanding of the brain.

"Most of modern neuroscience has its basis on observations of individual cases such as this one, that help to illuminate the complex working of the brain," Sirven said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.