Creature with Interlocking Gears on Legs Discovered

Gears are ubiquitous in the man-made world, found in items ranging from wristwatches to car engines, but it seems that nature invented them first.

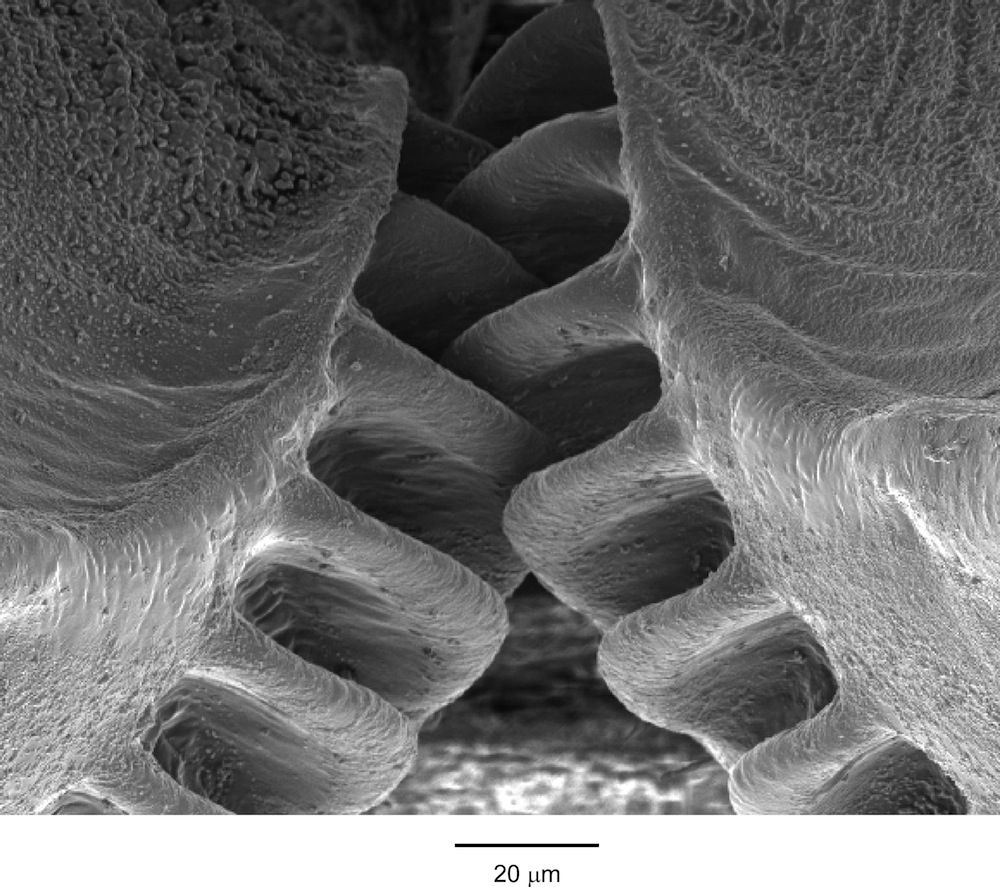

A species of plant-hopping insect, Issus coleoptratus, is the first living creature known to possess functional gears, a new study finds. The two interlocking gears on the insect's hind legs help synchronize the legs when the animal jumps.

"To the best of my knowledge, it's the first demonstration of functioning gears in any animal," said study researcher Malcolm Burrows, an emeritus professor of neurobiology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

Burrows and a colleague captured the gears' motion using high-speed video. As the young bug prepares to leap, it meshes the gear teeth of one leg with those of the other, like cocking a gun. Then, the insect releases its legs in one smooth, explosive motion. [See Video of the Insect Gears in Action]

Hopping in sync

Each leg sports a curved strip of 10 to 12 gear teeth that attach to the trochantera on the insect's legs. These structures were described in 1957, but no one had demonstrated that the gears were functional, Burrows told LiveScience.

Insects' hind legs can be arranged in two ways. The legs of grasshoppers and fleas move in separate planes at the sides of their body, whereas those of champion jumping insects, such as planthoppers, move beneath their body along the same plane. Thus, planthoppers' legs need to be tightly coupled.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If there were to be a slight timing difference between the legs, then the body would start to spin," Burrows said.

The gears synchronize the movement of the hind legs to within about 30 microseconds of each other — much faster than the nervous system could achieve, according to the study findings, detailed in the Sept. 13 issue of the journal Science. [The 7 Most Amazing Bug Ninja Skills]

Sometimes, Burrows observed that the gears slipped past one another, but when they finally engaged, the two legs became synced.

Burrows did an experiment with a dead planthopper: When he pulled one of its legs, both of them extended rapidly. Thus, the mechanics of the skeletal system alone can synchronize the legs, he said.

Gears are for kids

The cogs are only found in immature planthoppers, or nymphs, and are lost during the final molt. Adult planthoppers use friction between their legs to achieve the same effect as the gears.

Adults may ditch their gears partly because gear teeth can break, jeopardizing the insect's survival, Burrows said. Nymphs shed their exoskeleton five or six times before reaching adult size, and could correct the damage, whereas adults are stuck with one body.

Adults also have larger, more rigid bodies, so friction could be a more effective way to sync up their legs.

"It's very exciting to see one after another component of human mechanical engineering being discovered in the living world, too," said Alexander Riedel, curator of the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe in Germany, who was not involved in the research.

Riedel suggested another reason the adult insects lack gears could be that unlike nymphs, adults have wings, which could help direct their flight.

There are a few other animals that possess structures resembling gears. The cogwheel turtle, as its name suggests, has a gear on its shell, which is purely decorative. Some reptiles have cogwheel heart valves that increase the resistance to blood flow. And some insects have gearlike knobs that are used to produce chirping sounds. But none of these structures functions as a gear, per se.

Burrows originally came across gear-legged insects in a colleague's garden in Germany. He searched in vain for them at home in England.

"Then, I asked my 5-year-old grandson if he could find them, and he found some in the garden," Burrows said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.