A History of Elves

Elves have been a popular subject in fiction for centuries, ranging from William Shakespeare's play "A Midsummer Night's Dream" to the classic fantasy novels of J.R.R. Tolkien 300 years later. Probably the most famous of these magical creatures are the elves that work for Santa Claus at the North Pole.

Like fairies, elves were said to be diminutive shape-shifters. (Shakespeare's elves were tiny, winged creatures that lived in, and playfully flitted around, flowers.) English male elves were described as looking like little old men, though elf maidens were invariably young and beautiful. Like men of the time, elves lived in kingdoms found in forests, meadows, or hollowed-out tree trunks.

Elves, fairies, and leprechauns are all closely related in folklore, though elves specifically seem to have sprung from early Norse mythology. By the 1500s, people began incorporating elf folklore into stories and legends about fairies, and by 1800, fairies and elves were widely considered to be simply different names for the same magical creatures.

As with fairies, elves eventually developed a reputation for pranks and mischief, and strange daily occurrences were often attributed to them. For example, when the hair on a person or horse became tangled and knotted, such "elf locks" were blamed on elves, and a baby born with a birthmark or deformity was called "elf marked."

Indeed, our forefathers trifled with elves at their peril. According to folklorist Carol Rose in her encyclopedia "Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins" (Norton, 1998), though elves were sometimes friendly toward humans, they were also known to take "terrible revenge on any human who offends them. They may steal babies, cattle, milk, and bread or enchant and hold young men in their spell for years at a time. An example of this is the well-known story of Rip Van Winkle."

Santa's little helpers

Modern Christmas tradition holds that a horde of elves works throughout the year in Santa's workshop at the North Pole making toys and helping him prepare for his whirlwind, worldwide sleigh ride to homes on Christmas Eve. That depiction, however, is relatively recent.

Santa Claus himself is described as "a right jolly old elf" in the classic poem "A Visit From St. Nicholas," or "The Night Before Christmas," written by Clement Clark Moore in 1822. In 1856, Louisa May Alcott, who later wrote "Little Women," finished, but never published, a book titled "Christmas Elves," according to Penne L. Restad in the book "Christmas in America: A History" (Oxford University Press, 1996).

The image of elves in Santa's workshop was popularized in magazines of the mid-1800s. In 1857, Harper's Weekly published a poem titled "The Wonders of Santa Claus," which included the lines:

"In his house upon the top of a hill, And almost out of sight, He keeps a great many elves at work, All working with all their might, To make a million of pretty things, Cakes, sugar-plums, and toys, To fill the stockings, hung up you know By the little girls and boys."

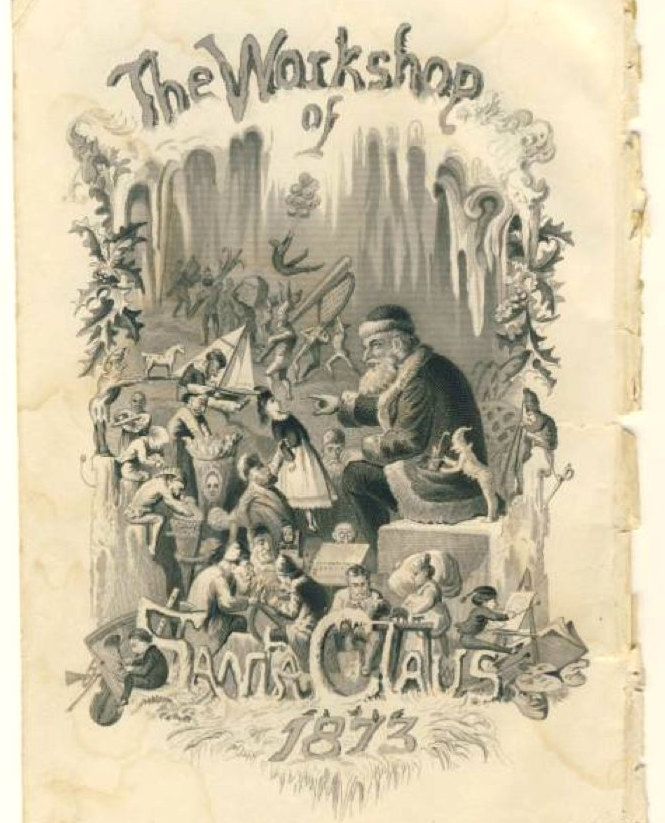

Godey's Lady's Book, another influential magazine, featured an illustration in its 1873 Christmas issue titled "The Workshop of Santa Claus," which showed Santa surrounded by toys and elves. A caption read, "Here we have an idea of the preparations that are made to supply the young folks with toys at Christmas time," according to Restad. Meanwhile, an editorial in that same issue addressed the realities of toymaking: they were not made by magical elves but by poor foreigners: "Whole villages engage in the work, and the contractors every week in the year go round and gather together the six days' work and pay for it."

The idea of Santa overseeing a workforce of toymaking elves played up the romantic vision of American capitalism, according to Restad. "Santa reigned without opposition over a vast empire, truly a captain of industry," Restad wrote, with the usually nameless elves standing in for largely anonymous immigrant workers.

The elves of Iceland

It's only recently that elves have been confined to plays, books, and fairy tales. In centuries past, belief in the existence of fairies and elves was common among both adults and children. The belief is still strong in some places. In Iceland, for example, about half of the residents believe in elf-like beings known as the "huldufolk" (hidden people), or at least don't rule out their existence.

According to author D.L. Ashliman in the book "Folk and Fairy Tales: A Handbook" (Greenwood Publishing, 2004), Eve was embarrassed that her children were dirty when God came to visit, so she hid them away and lied about their existence. God knew of her deceitfulness and proclaimed "What man hides from God, God will hide from man." These children then became the "hidden folk" of Iceland who often make their homes in large rocks.

The supernatural beliefs are so strong in Iceland that many road construction projects have been delayed or rerouted to avoid disturbing the elves' homes. When the projects aren't first stopped by residents trying to protect the elves, they seem to be thwarted by the elves themselves.

For example, in the late 1930s, construction began on a road near Álfhóll, or Elf Hill, the most famous elf residence in the city of Kópavogur. The construction was set to bring the road right through Álfhóll, which would have essentially destroyed the elves' home. At first, construction was delayed due to money problems, but when the work finally began a decade later, the workers encountered all sorts of problems from broken machinery to lost tools. The road was subsequently rerouted around the hill, rather than through it, according to The Vintage News.

Later in the 1980s, the same road was set to be raised and paved. When the workers reached Álfhóll and were about to demolish it, the rock drill broke into pieces. Then the replacement drill broke as well. At this point, the workers were spooked and refused to go near the hill. Álfhóll is now protected as a cultural heritage.

Icelandic laws were written in 2012 stating that all places reputed for magic or are connected to folktales, customs or national beliefs should be protected for their cultural heritage, according to the Iceland Monitor. Interestingly, however, accidental damage to elf residences seem to come to light almost immediately.

Evolving elves

Over time and across different cultures, a certain type of elf emerged, one with a somewhat different nature and form than the mischievous and diminutive sprites of yore. Some elves, such as those depicted in J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, are slender, human-sized, and beautiful, with fine — almost angelic — features. Tolkien's characters were drawn largely from his research into Scandinavian folklore, and therefore it's not surprising that his elves might be tall and blond. Though not immortal, these elves were said to live hundreds of years. They have also become a staple of modern fantasy fiction.

Gary Gygax, co-creator of the seminal role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, was not only influenced by Tolkien's elves but also instrumental in popularizing them, even including elves as one of the character races (along with humans) that gamers could play.

In either form, elves are strongly associated with magic and nature. As with fairies, elves were said to secretly steal healthy human babies and replace them with their own kind. These changelings appeared at first glance to be human babies, but if they became seriously sick or temperamental, parents would sometimes suspect that their own child had been abducted by elves. There were even legends instructing parents on how to get their real child back from its elven abductors.

Each generation seems to have their own use for elves in their stories. Just as leprechauns have historically been associated with one type of work (shoemaking), it is perhaps not surprising that many common (and commercial) images of elves depict them as industrious workers — like Santa's elves or even the Keebler cookie-baking elves. Folklore, like language and culture, is constantly evolving, and elves will likely always be with us, in one form or another.

Additional reporting by Traci Pedersen, Live Science contributor, and Tim Sharp, Reference editor.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.