Hawaii Volcanoes: Like Biggest Stack of Pancakes on Earth

The biggest active volcano in the world is a towering stack of lava layers laid down over a million years, a new study finds.

The research could help solve a long-standing debate over how Hawaii's volcanic islands formed.

According to the study, the massive volcanoes on Hawaii's Big Island grew layer by layer, like a giant stack of lava crepes. The discovery counters a popular model that proposes the island's bulk is mostly cooled magma, frozen in place inside the volcano before erupting.

"The islands have formed primarily through lava flows, not internal emplacement of magma, as previously thought," said Ashton Flinders, lead study author and a graduate student with joint appointments at the University of Rhode Island and the University of New Hampshire.

Hawaii's Big Island is home to five massive volcanoes. The tallest active volcano on the island is Mauna Loa, which rises 13,678 feet (4,169 meters) above the ocean surface. With its height measured from the seafloor, Mauna Loa even stretches above Mount Everest, reaching 30,080 feet (9,168 m). [5 Colossal Cones: Biggest Volcanoes on Earth]

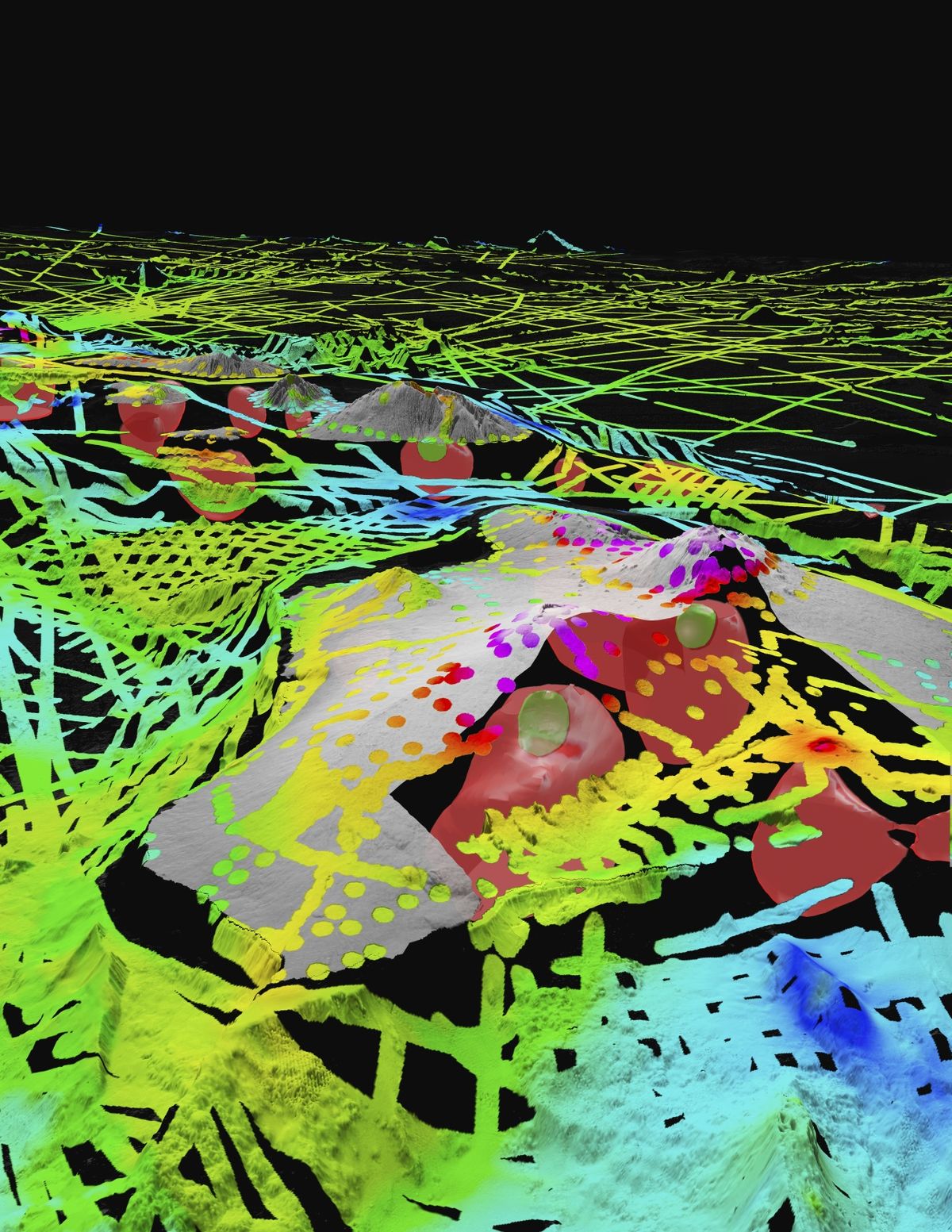

Tiny changes in Earth's gravity revealed Hawaii's hidden, layered structure. Fluctuations in the gravity field reflect changes in mass. The densest rocks have the strongest pull, and gravity-sensing instruments can detect these subtle variations caused by denser or lighter rocks.

Flinders and his colleagues used gravity data from a recent ship survey and older land surveys to estimate how much of the island was intrusive rock, which has a higher density than lava.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The gravity data indicates Hawaii and Kauai are only 10 to 30 percent dense, intrusive rock, Flinders said. Previous studies had suggested that intrusions — magma that cools underground — accounted for 65 to 90 percent of the total volume of Hawaii.

The intrusive rock is likely molten magma that squeezed into Hawaii's rift zones, which are linear fractures that extend from the surface deep into the crust. The magma gets stuck and cools, helping the volcano grow in width, scientists think.

The rest of Hawaii — about 70 percent — built up slowly and steadily from lava flows. Researchers think the first lava punched through the seafloor sometime around 1 million years ago and that the island emerged from the sea about 400,000 years ago.

Flinders said he sees other interesting details about the islands in the gravity data, the most detailed compilation produced in decades. There are signs of small volcanoes entombed beneath lava flows on the Hana Ridge offshore Maui.

The team may have even found a teeny, previously unrecognized volcano, which they named Uwapo, between Kauai and Oahu. Work is underway to determine if Uwapo is really a separate volcano, Flinders said. "The debate is still out, but I'd say yes. I used the nature of its gravity field to argue that it appears to have a separate magmatic source than those volcanoes around it," Flinders said.

The findings were published July 3 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science's OurAmazingPlanet.