As Constrictor Attacks Continue, Look to the Snake Trade (Op-Ed)

Wayne Pacelle is the president and chief executive officer of The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). This Op-Ed is adapted from a post on the blog A Humane Nation, where the content ran before appearing in LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

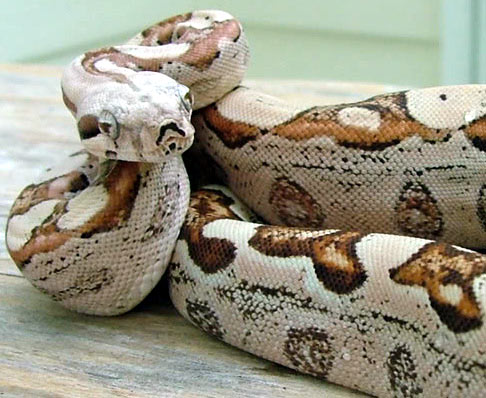

A New York area animal control officer, under investigation for workers' compensation fraud, attracted headlines last month after law enforcement discovered that he had 850 snakes, including Burmese pythons, in his garage. Richard Parrinello was selling pythons and boa constrictors as pets over the Internet, even though state law forbids the possession of certain species.

It's an extraordinary circumstance, but hardly unique. There are millions of large constricting snakes traded via the Internet through private dealers like Parrinello, at reptile shows, and also at pet stores. In so many cases, those pet dealers are keeping the snakes in warehouse-type conditions, often inside exceptionally small, stacked, plastic containers no larger than a shoe or sweater box, and selling them through websites and at reptile expos.

It's not good for the snakes, and there are all sorts of collateral impacts, mainly public-safety and ecological effects.

Every day, I hear about incidents of snakes on the loose in some community — in recent days, there were incidents in Florida, Massachusetts, Missouri, Pennsylvania and Vermont. A few weeks ago, two young boys were strangled to death by an African rock python in New Brunswick, Canada. And last week, there was a Siberian Husky strangled by a rock python believed to be from an established population of this highly dangerous, non-native snake in Miami-Dade County, Fla., as the dog's owners frantically and helplessly tried to break the vise-like grip of the snake. The family is now grieving and have attested that it was one of the most traumatic experiences of their lives.

At The HSUS, we've logged hundreds of incidents, such as attacks, escapes, or intentional releases of pythons, boa constrictors or anacondas, reported in nearly every state in the country. They've turned up in apartment buildings, gardens, vehicles and high-school football fields.

They're also showing up in natural areas, wreaking havoc for native species. Some studies report massive losses of opossums, raccoons and even bobcats in the Everglades, probably due to large, self-sustaining populations of non-native snakes in south Florida. The original pythons who became established in the state almost certainly were pet-trade cast-offs or escapees.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eighteen months ago, the administration of President Barack Obama took a half-step on the issue, banning trade in four of nine large, constrictor snakes. It was the clamoring of reptile breeders and snake owners, and their ludicrously exaggerated reports of economic losses, that prevented the White House from taking more comprehensive action. A risk assessment done by the U.S. Geological Survey found nine snake species posing a medium or high risk of colonizing habitats and causing impacts on native species. Yet the administration banned trade in only four species of constricting snakes. Since then, trade has, for the most part, shifted to the other five species.

We need a federal policy prohibiting the import and interstate transport of the other five species for the pet trade. Why risk the lives of people and animals, put law enforcement and other first responders in unnecessary danger, jeopardize highly sensitive ecosystems and species we are working to recover, and cost taxpayers millions of dollars in terms of exotic animal control, just because some people want these types of exotic wildlife in their homes?

The Second Amendment doesn't say a word about the right to possess anacondas or boa constrictors. And the costs to society far exceed the benefits.

Pacelle's most recent Op-Ed was "When People and Wildlife Conflict, Humane Solutions Work Best" This article was adapted from "Snakes on Planes, in Garages, and Everywhere Else," which first appeared on the HSUS blog A Humane Nation. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.