Scientists Speak Out on Harm of Research Hiatus (Op-Ed)

Perrin Ireland is senior science communications specialist for the Natural Resources Defense Council. This post was adapted from one that originally appeared on the NRDC blog Switchboard. Ireland contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Last Saturday, Caitlin MacKenzie finished setting up the common gardens in Acadia National Park that will provide data for her Ph.D. research on the effects of climate change on plants. The setup was a two-week team effort — 270 trees, three native species, three raised beds — that she pulled off with help from Friends of Acadia volunteers. The group built raised beds, a hideous chore if you've ever tried it, hauled soil, dug and dug some more, transplanted the trees and watered them.

MacKenzie hired a local college student (with funds from a Cooperative Agreement with the park) to water the new transplants four times a week until the first hard frost. On Monday, he watered the plants for the first time. On Tuesday, the government shut down and the park was locked, blocking access to the gardens and the new, vulnerable transplants. MacKenzie reports that it's been warm and sunny in Acadia since her team left, and rain isn't forecast until this week.

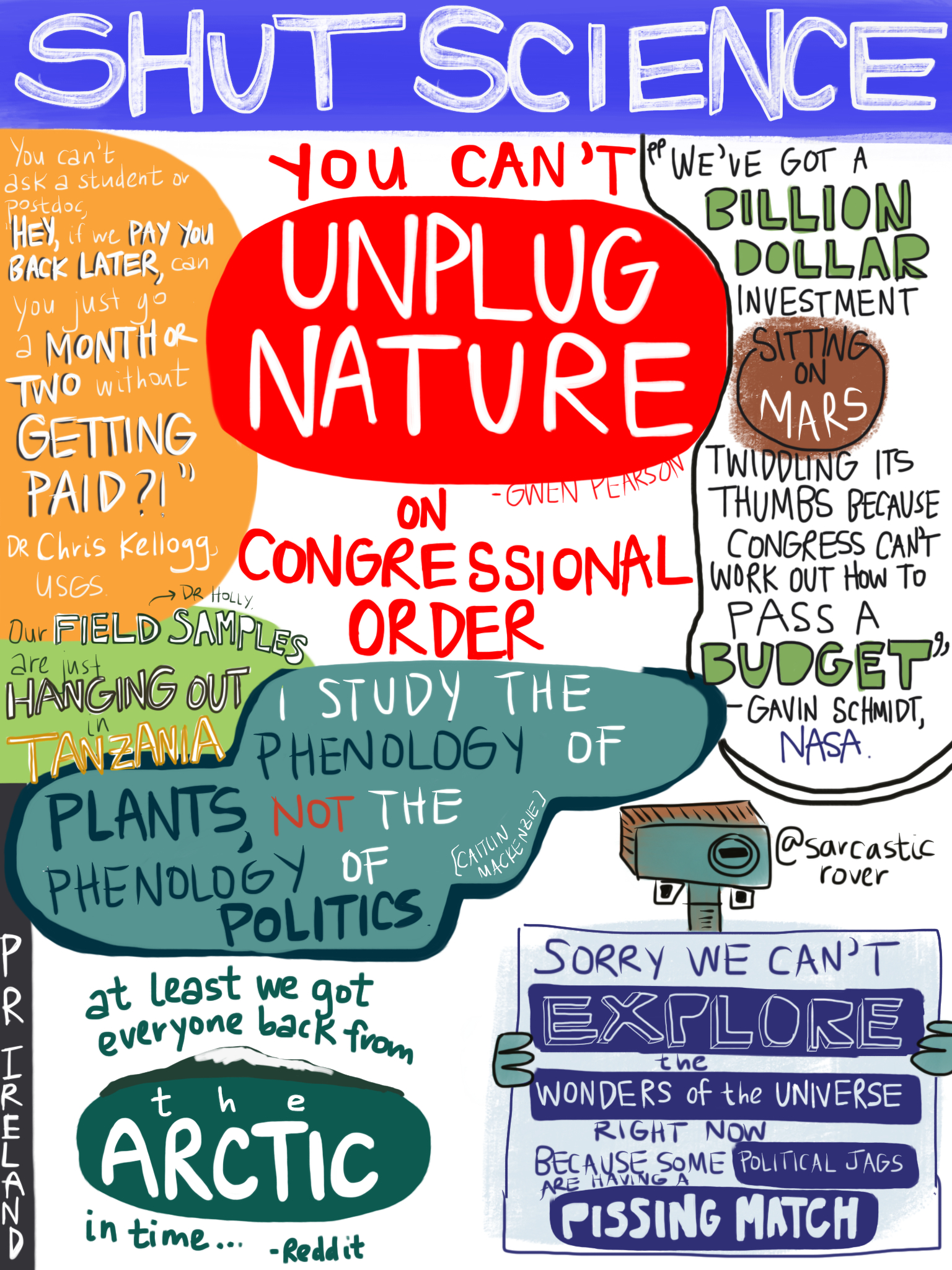

"I study phenology — the timing of biological events," she says. "I would love to be able to focus solely on the phenology of plants, instead of also worrying about the phenology of politics."

MacKenzie worries about the survival of the tree transplants without regular watering. "I could lose an entire field season if these plants do not survive. Almost all of the work that the volunteers and I poured into this project over the two weeks in September will be erased."

Most of the scientists I spoke with are all too aware that nature doesn't plan around disagreements in the U.S. Congress, and they feel that Congress doesn't understand that a scientist can't always survive "pushing the pause button" on research. As MacKenzie says, "In my field, long term records and monitoring are useful and important because they are continuous."

For example, October is a critical month for those that study birds , as it's migration time. This year, however, federal scientists are unable to tag (or band) migrating birds to monitor themand keep track of birds banded last season. Bird banding data is used to sleuth out reasons different bird species might be in peril. Birds help reveal when there are problems in Earth's ecosystems , from harmful toxins to the drivers of habitat loss for birds or their response to climate change. Scientists rely on collective data from the past 50 years to paint a complete picture of birds on Earth today.

"Birds are migrating," says Gwen Pearson, an entomologist and science communicator. "Crops are (supposed to be) harvested. Biological (and geological and hydrological!) life continues to happen all around us, except now scientists are physically and financially prohibited from studying it. We will have a big hole in our data this year."

Pearson helped me understand the importance of tracking birds during their yearly migration. She also wrote about the implications of the government shutdown for conservation and agricultural science in her column for Wired last Wednesday.

Holly Menninger, a scientist at North Carolina State University who coordinates the citizen-science project Wild Life of Our Homes, has recently started studying how humans' relationships with microbes have changed over evolutionary time, from primitive to modern homes, which might have important implications for human health and well-being. Her lab's collaborators in Tanzania have spent this field season wiping Q-tips over the surfaces of leaves and branches in chimpanzee nests, which are viewed as a feasible comparison for what a primitive human home might have been like. Sending samples like this into the United States requires U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) permission, which is impossible to get right now, and the lab won't be able to receive the samples until the shutdown is over, at which point the Tanzanian collaborators won't be able to send them, as their field season is winding down. This is a costly loss of potentially exciting research.

With the grant wave stalled, researchers also don't have anticipated grants coming in, and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) are not accepting or reviewing new grant proposals. Independent organizations that house principal investigators with long-term NSF grants, which also pay students and technicians, could be stalled if the shutdown lasts more than a single pay cycle. I spoke to one scientist who feels relieved that she's not trying to submit a grant proposal for this funding cycle, as there's a frightening possibility that NSF and NIH may not fund anything this year.

Government scientists are unable to take outside jobs to make some money in the meantime, as they're technically still government employees, and they also need to pause any ongoing collaborations with independent scientists. Several academics I spoke to haven't been able to reach governmental collaborators on their work emails all week. This, combined with funding cuts from the sequester, reveals a dire state of science in the United States: It's undervalued, underfunded and currently, devastatingly understaffed.

Dr. Chris Kellogg, who studies the microbiomes of deep-sea corals , works at the United States Geological Survey (USGS). She's one of about 8,500 scientists at the agency, which conducts research that supports nearly every other federal agency. Kellogg is on furlough, and just one member of her lab, their lab manager, is allowed to go in and maintain the lab for an hour a week during shutdown. USGS earthquake researchers have been deemed essential and are still at work, but furloughed hurricane respondents have been told that if a storm comes up, they'll just be called back. It's a felony for the researchers to take any research home or continue with their work during shutdown.

Ordinarily, Kellogg says, she loves her job. Working for the government as a scientist gives her the freedom to do research, travel and conduct field work without the commitment to teach that she would have at an academic institution. She also doesn't have to constantly search for funding because she's specifically employed by USGS internal programs. As she says, the downside is, "younger people might look at that and say, that sounds great, but you might get sent home for who knows how long!" Plus, within the scientific community, a restriction on any travel is detrimental to professional development. Science conferences are not only spaces where people share ideas, but where they become acquainted with each other. As a young researcher trying to become established in the scientific community, not going to conferences, and not sharing your research in that way, can be damaging to your credibility.

Karen James, of the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory, pointed out that the element of stress in this equation is significant. "Science is carried out by human beings that need to get paid. In some causes, yes, you can press pause. In other cases you can't survive pressing pause." As Kellogg puts it, "You can't ask a student or a postdoc, 'Hey, if we can pay you back later, can you just go a month or two without being paid and we'll catch you when this all gets sorted out?' No, they have to pay the rent and would like to eat."

The silver lining for some scientists has been sharing their stories online. SouthernFriedScience has created an online, anonymous thread where scientists can comment on their concerns and frustrations about leaving a major experiment halfway through. And ReddIt has featured a couple of threads of anonymous commentary from researchers who seem mostly concerned about their students and postdocs that live paycheck to paycheck.

"Having identified myself online as being a furloughed scientist, at least two people have offered to have me over for dinner," said Kellog. "Even though they live too far away, I still appreciated the offer!"

Ireland's most recent Op-Ed was "When Hitting the Beach, Stay Alert for Sewage". The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This article was originally published on LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.