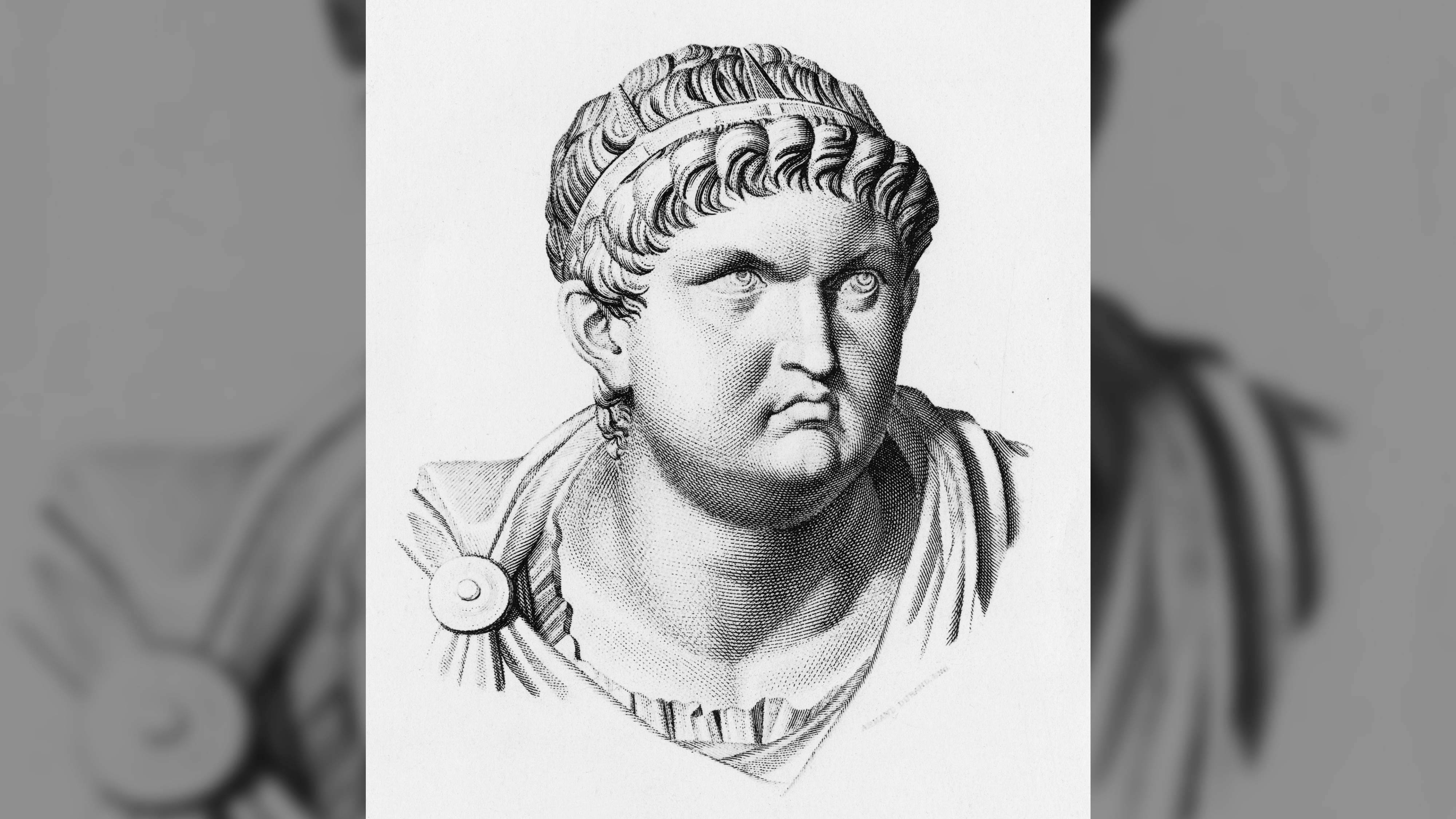

Emperor Nero: Facts & biography

Nero is one of the most infamous of Rome's emperors, but he may not be the complete tyrant history remembers.

Nero was the emperor of Rome from A.D. Oct. 13, 54 to June 9, 68 (lived A.D. 37 to 68). He became the ruler of the Roman Empire after the death of his adopted father, the Emperor Claudius. The last ruler of what historians call the "Julio-Claudian" dynasty, he ruled until he killed himself, having either assassinated or been abandoned by his allies.

Famously known for the apocryphal story that he fiddled while Rome burned in a great fire, Nero has become one of the most infamous men who ever lived. During his rule, he murdered his own mother, Agrippina the Younger; his first wife, Octavia; and allegedly, his second wife, Poppaea Sabina. In addition, ancient writers claim that he started the great fire of Rome in A.D. 64 so that he could rebuild the city center with a new palace.

Yet, despite the numerous charges that have been leveled by ancient writers, there is evidence that Nero enjoyed some level of popular support. He had a passion for music and the arts, an interest that culminated in a public performance he gave in Rome in A.D. 65. Also, while he was blamed for starting the fire, he took it upon himself to organize relief efforts, and ancient writers make other allusions to acts of charity that he performed.

"He let slip no opportunity for acts of generosity and mercy, or even for displaying his affability," wrote the otherwise critical Suetonius in the 2nd century A.D.

Nero's early life

Nero was born in Antium, in Italy, on A.D. Dec. 15, 37, to his mother, Agrippina the Younger, and his father, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. His father, a former Roman consul, died when he was about 3 years old, and his mother was banished by the Emperor Caligula, leaving him in the care of an aunt. His name at birth was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus.

After the murder of Caligula in A.D. Jan. 41, and the ascension of Emperor Claudius shortly afterward, mother and son were reunited. His ambitious mother would go on to marry Claudius (who was also her uncle) in A.D. 49, and she saw to it that he adopted her son, giving him a new name that started with "Nero." His tutors included the famous philosopher Seneca, a man who would continue advising Nero into his reign, even writing the proclamation explaining why Nero killed his mother.

The newly adopted son would later take the hand of his stepsister, Octavia, in marriage, and become Claudius' heir apparent, the emperor choosing him over his own biological son, Britannicus (who died shortly after Nero became emperor).

After the death of Claudius in A.D. 54. (possibly by being poisoned with a mushroom), Nero, with the support of the Praetorian Guard and at the age of 17, became emperor. "Seneca wrote a remarkable accession speech, where Nero promised to uproot the corruption that plagued Claudius’ court and return powers to the Senate. And while others had promised this before, incredibly, Nero actually stuck to his words — reversing egregious laws, and restoring authority to the Senate," wrote Hareth Al Bustani, author of "Nero and the Art of Tyranny" (Independently published, 2021), in All About History.

"The emperor was a man who appealed to all classes alike — he handed 400 sesterces to every citizen, gave the Praetorians free grain, greeted soldiers by name, introduced a salary for impoverished senators, built a beautiful new market, scored military victories abroad, held the most spectacular games Rome had ever seen, and tackled predatory tax farming practices," wrote Al Bustani.

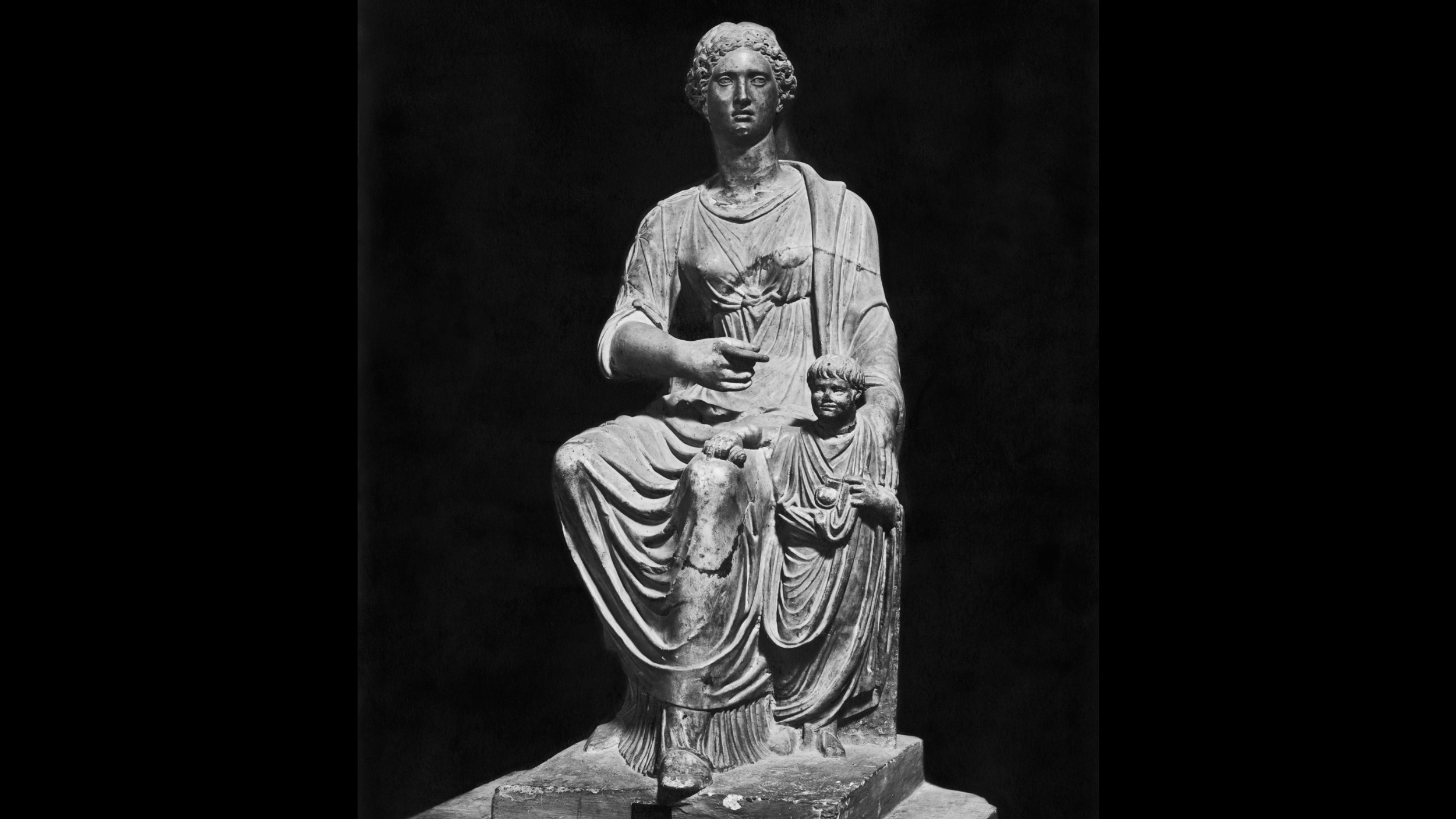

However, his mother Agrippina remained a powerful influence. In the first two years of Nero's reign, his coins depicted him side by side with his mother. She "managed for him all the business of the empire … she received embassies and sent letter to various communities, governors and kings …" wrote Cassius Dio who lived A.D. 155-235. according to David Shotter in "Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome" (Routledge, 2014).

Nero kills Agrippina

Nero and his mother appear to have had a falling out within about two years of his becoming emperor. Her face stopped appearing on Roman coins after A.D. 55, and she appears to have lost power in favor of Nero's top advisers, Seneca and Burrus, the commander of the Praetorian Guard who advised him on military affairs.

"When a group of Armenian diplomats came to visit, instead of sitting at her own dais, she attempted to assert herself by strolling over and sitting next to Nero — as if she were his equal. Desperate to prevent this humiliation, without embarrassing Agrippina, Seneca ran over and met her half way, physically blocking her from joining her son," wrote Al Bustani. They fell out further when Nero began cheating on his wife; a marriage Agrippina had worked hard to arrange.

Officially, the reason given for Nero's orders to kill his own mom in A.D. 59. was that she was plotting to kill him. Whatever the reasons, Nero knew that he was making a decision that could come back to haunt him. "This was a crime that will have caused revulsion in the Roman world, for the mother was that most sacred of icons within the Roman family," wrote Shotter.

Nero, not trusting his Praetorian Guard to carry out the killing, ordered naval troops to sink a boat that she would be sailing on. This first attempt failed, with his mother swimming to shore. Nero then ordered assassins to do the job directly.

Tacitus ( A.D. 56-120) wrote that when the troops came to kill her, she told them if "you have come to see me, take back word that I have recovered (from the sinking boat), but if you are here to do a crime, I believe nothing about my son, he has not ordered his mother's murder," according to Jürgen Malitz in his book "Nero" (Beck C.H., 2013).

However, the killing also fulfilled a prophecy Agrippina had been told not long after Nero had been born. "Keen to discover what the gods had in store for her young boy, Agrippina consulted an astrologer, who predicted that he would one day rule, but only after killing his own mother. She supposedly spat back, 'Let him kill me, only let him rule!'," wrote Al Bustani.

Nero, much to his relief, found his actions applauded. The senators said that they believed his life was at risk and congratulated him on killing his own mother. Seneca himself wrote Nero's report on the murder to the Senate.

Becoming a despot

The death of Agrippina appears to have marked an important change in Nero's rule, as he paid less attention to his advisors, according to Al Bustani. "The emperor had always dreamed of racing chariots and singing in public — but Seneca and Burrus had kept his worst excesses under control, by having him practice in private. Now, rebranding himself as Apollo — the sun god of chariots and song — he began paving the way towards his public debut," wrote Al Bustani.

More festivals and public celebrations of the emperor followed, many bringing Greek traditions to Rome, much to the annoyance of the Roman elite, but to the delight of the plebeian class. In the meantime, Nero's marriage to Octavia was falling apart. They were unable to conceive a child, and the two were estranged by A.D. 62.

"After several vain attempts to strangle her, he divorced her on the ground of barrenness, and when the people took it ill and openly reproached him, he banished her besides; and finally he had her put to death on a charge of adultery that was so shameless and unfounded, that when all who were put to the torture maintained her innocence, he bribed his former preceptor Anicetus to make a pretended confession that he had violated her chastity by a stratagem," wrote Roman historian Suetonius, as translated by J. C. Wolfe (Heinemann, 1914)

Nero may have taken the step of killing her as a way to protect his position as emperor. As Shotter notes, a large part of Nero's legitimacy as emperor was based, not only on the fact that he was the adopted son of Claudius, but that he was married to his daughter. The death did not go over well with the public, however, as Al Bustani points out it sparked riots on the streets when news spread that were met with brute force by the emperor.

Second marriage and tragedy

Nero would go on to marry the already pregnant Poppaea Sabina in that same year, A.D. 62, and she would give birth to their daughter (who lived only about three months) in January, A.D. 63. He took the death of their infant daughter hard and had the baby deified.

In A.D. 65, while Poppaea was pregnant again, she died. Ancient writers say Nero killed her with a kick to the belly. However, a poem from Egypt casts doubt on this, showing Poppaea in the afterlife wanting to stay with Nero.

"The poet is trying to tell you [that] Poppaea loves her husband and what it implies is this story about the kick in the belly cannot be true," said Paul Schubert, a professor at the University of Geneva and the lead researcher who worked on the text, in an interview with Live Science. "She wouldn't love him if she had been killed by a kick in the belly."

The Great Fire of Rome

On the night of A.D. July 18, 64, a fire started in the Circus Maximus that would burn out of control, raging for six days, leaving little of the city untouched. Historians agree that Nero was not playing a fiddle as Rome burned, but at the time it occurred, Nero was at Antium. He immediately returned to Rome to oversee relief efforts.

"Nero responded swiftly, opening up his gardens to the homeless, hauling in huge quantities of food, and launching a massive reconstruction drive. However, the city was in shock. When Nero unveiled plans for a new almighty palace, the Golden House — complete with a revolving dining room and perfume dispensers — which would gobble up huge parts of the city, some began to speculate that he had set the fire himself to make way for the vanity project," wrote Al Bustani.

While ancient writers tend to blame Nero for starting the fire, this is far from certain. Much of Rome was made with combustible material and the city was overcrowded.

After the flames died down Nero apparently tried to cast blame on the Christians, at the time a fairly small sect. "Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace," wrote Tacitus, according to Malitz. "Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as nightly illumination when daylight had expired."

While it is not known whether Nero started the fire, he did take advantage of the space it cleared. He started work on his new palace called the Domus Aurea (golden house), which was said, at the entranceway, to have included a 120-foot-long (37 meter) column that contained a statue of him.

Bloodshed in the empire

Nero's rule would have its share of bloodshed in places throughout the empire. In Britain, in A.D. 60, the Iceni Queen Boudica rose in rebellion after she was flogged and her daughters raped by Roman soldiers. Her husband, King Prasutagus, had made a deal with Claudius that would see him rule as a client-king. Upon his death in A.D. 59, the officials appointed by Nero ignored it, seizing Iceni land.

At first, Boudica was successful, overrunning a number of Roman settlements and military units. Ancient sources say that Nero considered evacuating the island, but this proved unnecessary as the Roman commander on the island Gaius Suetonius Paulinus massed a force of 10,000 men and defeated Boudica at the Battle of Watling Street.

Britain wasn't the only place where Rome had military trouble during Nero's reign. In the east, Rome fought, and essentially lost, a war with Parthia, having to give up plans to annex the kingdom of Armenia, which served as a buffer between the two powers. Additionally a rebellion in Judea in A.D. 67, near the end of Nero's reign, would eventually lead to the siege of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 and the destruction of the Second Temple. One effect of this was the abandonment of Qumran, the site where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found stored in nearby caves.

Back at home, there had been growing discontent with Nero, fueled by the Great Fire and concerns over his behavior. "A group of patricians were caught plotting to assassinate Nero and replace him with the statesman, Gaius Piso. Indicating the mood, when interrogated, the tribune Subrius Flavus explained, "I began to hate you when you turned into the murderer of your mother and wife — a chariot-driver, an actor, a fire-raiser." Growing increasingly paranoid, Nero tasked Tigellinus with uprooting the plotters; which he took as a license to wipe out his enemies, with even poor Seneca driven to commit suicide," wrote Al Bustani.

Nero in Greece

Not all of Nero's dealings throughout the empire ended in violence. In A.D. 66, not long after the death of his second wife and child, Nero embarked on a trip to Greece, which had been under Roman control for about two centuries by his time.

Always a lover of Greek culture, Shotter writes that Nero took part in several Greek festivals, taking home 1,808 first prizes for his artistic presentations. The Greeks also agreed to postpone the Olympic Games by one year so that Nero could compete in them, according to Miriam Griffin in "Nero: The End of a Dynasty" (Routledge, 2000).

That wasn't all they agreed to do, to the "athletic contests were added for the first time artistic competitions, which included singing and acting, for Nero's sake," wrote Edward Champlin in his book "Nero" (Belknap Press, 2003).

"In one dangerous race, he fell out of his chariot, but the Hellenic Judges in charge of the games nevertheless granted him the wreath of victory: he rewarded these traditionally unpaid officials with one million sesterces."

Shotter notes that Nero was so happy with the results of his trip to Greece that he rewarded the Greeks their "freedom," essentially tax exemption.

However, the trip to Rome acted as a distraction from events back in Rome. "Nero repeatedly ignored letters warning him of emerging rebellions back home. Having taken Tigellinus with him, Nero was even losing control of the Praetorians. It was only when Helius showed up in person that Nero decided to return — taking his sweet time to indulge in Rome’s only ever artistic triumph.

When he finally arrived back in Rome, he hardly ever spoke to anyone directly, lest he damage his singing voice; and when he did eventually summon the senate, rather than discussing the rebellion raging in Gaul, he gave them a lecture on musical instruments," wrote Al Bustani.

Death of Nero

By A.D. 68, the problems Nero faced had piled up. He had killed his mother, first wife and, by some accounts, his second. Additionally, the rebuilding of Rome, not to mention the construction of his "golden house," was putting a financial strain on the empire. This forced him to raise taxes wherever he could and even take religious treasures.

"Nero took votive offerings from temples in Rome and Italy as well as hundreds of cult statues from temples in Greece and Asia, after the fire of Rome in 64 A.D.," writes Richard Duncan-Jones in "Money and Government in the Roman Empire" (Cambridge University Press, 1998), who also notes that Nero reduced the size of the coins Rome minted.

Nero's support began to crumble. Shotter writes that in April of 64, a Roman governor in Gaul named Gaius Iulius Vindex renounced Nero and declared his support for Galba, then in Spain, for emperor. Although Vindex killed himself after his forces were defeated by German legions in May, it was enough to undo Nero.

Not long afterward, the Praetorian Guard, the force charged with guarding the emperor himself, renounced their support for Nero and the now former emperor was declared an enemy of the people by the Senate on June 8.

The following day, he killed himself. His last words were said to be "what an artist dies in me!" Shotter notes that his long-time mistress Acte was by his side and "ensured Nero a decent burial in the family tomb of the Domitii on the Pincian Hill in Rome."

Rome after Nero

After Nero's death, the Roman Empire plunged into chaos as a succession of short-lived emperors tried to gain control of the empire. According to Shotter, Nero still had a considerable deal of popular support and one of these emperors, Otho, even renamed himself "Nero Otho" in his honor.

Champlin wrote that people also refused to believe that Nero was actually dead. "Many believe that Nero did not kill himself in June of 68," he wrote. "As Tacitus (the ancient writer) admits, various rumors circulated about Nero's death and, because of them, many believed or pretended to believe that he was still alive."

Shotter also noted this, writing that "the decades that followed Nero's death saw a number of appearances in the East of imposters (or false Nero's)," a sign that some in the Roman Empire still approved of the man who, today, is known so infamously.

"Though Nero died at just 30-years-old, he left a legacy that would endure for thousands of years, with some denigrating him as the antichrist, and others, wishing he would return to save Rome from ruin," wrote Al Bustani.

Additional resources

Nero's mother, Agrippina, was an incredibly powerful and influential woman, but she wasn't the only powerful female figure from Roman history.

If you want to learn more about the role of emperor in Ancient Rome, then you should go back to the beginning and the story of Julius Caesar.

Bibliography

- "Ancient History Sourcebook" Fordham University

- "Nero and the Art of Tyranny" by Hareth Al Bustani (Sharpe Books, 2021)

- All About History issue 116

- "Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome" by David Shotter (Routledge, 2014)

- "Nero" by Jürgen Malitz (Beck C.H., 2013)

- "Suetonius with an English Translation" by J. C. Wolfe (Heinemann, 1914)

- "Nero: The End of a Dynasty" by Miriam Griffin (Routledge, 2000)

- "Nero" by Edward Champlin (Belknap Press, 2003)

- "Money and Government in the Roman Empire"by Richard Duncan-Jones (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

- Jonathan GordonEditor, All About History