SAN FRANCISCO — The ability to see using one's back, magnetic fingers or an ultraviolet sense of sight?

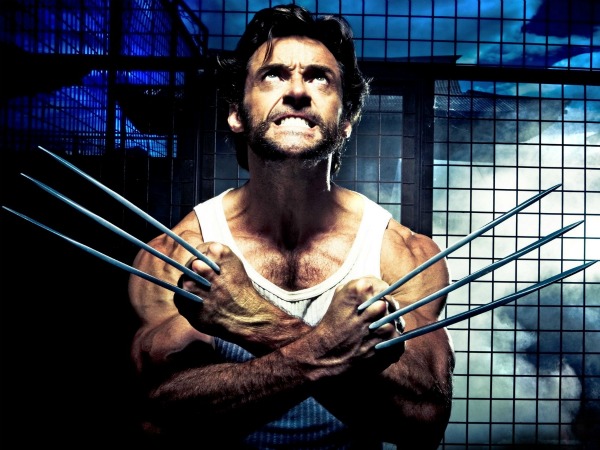

Those abilities may sound like the domain of X-Men mutants, but such innovations may not be far off, researchers say.

Because the sensations that humans (and other animals) experience from sense organs like the nose are all processed and interpreted similarly in the brain, those organs could be augmented, replaced and transformed to create human superpowers.

"The brain doesn't care what the peripheral devices are that you plug in, like eyes and ears and nose and mouth," said researcher David Eagleman, a neuroscientist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, on Sept. 28 at the Being Human conference, a daylong event focusing on questions about the science and mystery of the human experience. "These are plug-and-play peripheral devices and the brain will figure out how to use it." [Bionic Humans: Top 10 Technologies]

Sensory bubble

The human experience of the real world is mediated through the five senses, which for humans includes a narrow band of hearing, a tiny fraction of the "visible" light spectrum and a puny smell system that most dogs would deem pathetic.

Animals experience the world very differently. For instance, bats navigate by sound, cows have magnetic compasses that help them feel the Earth's magnetic field, and star-nosed moles have a 20-fingered nose with thousands of touch receptors that allows them to feel their way through dark, subterranean tunnels, Eagleman said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now many scientists, banking on brain similarities between these animals and humans, are developing technologies to give humans an expanded repertoire of supersenses.

Decades' worth of research shows humans have the radical capacity to reinterpret sensory information. For instance, in a 1969 article published in the journal Science, researchers showed that people could be trained to see an image of a face if that visual data was translated into different amounts of pressure on their backs, Eagleman said. (Even without augmentation, blind people can navigate somewhat using sound, research suggests.)

Cochlear implants allow the deaf to hear by replacing the sensory organs in the ear with electrical devices.

And sonic glasses can convert audio streams into visual information.

"After a few weeks, people have direct perceptual experience, essentially seeing sound," Eagleman said.

A new technology called Brainport translates visual data into sensory information that is transmitted to the brain via electrodes on the tongue. People seeing with their tongues have used Brainport while rock-climbing, Eagleman said.

Eagleman's lab is currently developing a vest with tactile sensors that convert sound into touch. The idea is to give those who are deaf the ability to hear via touch.

"This can be 100 times cheaper than you can do a cochlear implant, and it doesn't require an invasive surgery," Eagleman said.

Future additions

The five traditional senses may even be so yesterday: With newer technology, scientists aim to create completely new senses. For instance, some researchers are developing technologies to allow humans to sense weather patterns from up to 200 miles (320 kilometers) away, or to process the minute fluctuations of the stock market every second.

Other sensory pioneers are getting magnets made of the element neodymium implanted into their fingertips so they can sense the magnetic field around them. Some even say they can repair their electronics just by feeling the "color" of the magnetic field around broken devices, Eagleman said.

"We are no longer a natural species in the sense that we don't have to wait for Mother Nature's sensory gifts on her timescales," Eagleman said. "Nature has given us the tools we need to construct our own experiences."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.